Abstract

Background

In severe cases, SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), often treated by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). During ECMO therapy, anticoagulation is crucial to prevent device-associated thrombosis and device failure, however, it is associated with bleeding complications. In COVID-19, additional pathologies, such as endotheliitis, may further increase the risk of bleeding complications. To assess the frequency of bleeding events, we analyzed data from the German COVID-19 autopsy registry (DeRegCOVID).

Methods

The electronic registry uses a web-based electronic case report form. In November 2021, the registry included N = 1129 confirmed COVID-19 autopsy cases, with data on 63 ECMO autopsy cases and 1066 non-ECMO autopsy cases, contributed from 29 German sites.

Findings

The registry data showed that ECMO was used in younger male patients and bleeding events occurred much more frequently in ECMO cases compared to non-ECMO cases (56% and 9%, respectively). Similarly, intracranial bleeding (ICB) was documented in 21% of ECMO cases and 3% of non-ECMO cases and was classified as the immediate or underlying cause of death in 78% of ECMO cases and 37% of non-ECMO cases. In ECMO cases, the three most common immediate causes of death were multi-organ failure, ARDS and ICB, and in non-ECMO cases ARDS, multi-organ failure and pulmonary bacterial ± fungal superinfection, ordered by descending frequency.

Interpretation

Our study suggests the potential value of autopsies and a joint interdisciplinary multicenter (national) approach in addressing fatal complications in COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) is used for refractory severe acute respiratory failure with a survival rate of about 50% [1]. The interface between blood and non-biological ECMO circuit elements requires therapeutic anticoagulation, predisposing patients to an increased risk of bleeding.

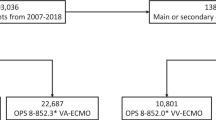

Based on a recent analysis from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry including 7579 patients from 2007 to 2018, 37% experienced any bleeding event, and 21.2% experienced bleeding combined with a thrombotic event. While the most common bleeding events with cannulation (15.5%) and surgical site (9.6%) bleeding are easy to handle, intracranial hemorrhage occurred in only 4.5% and has been consistently associated with poor survival [2]. Other retrospective studies reported intracranial hemorrhage in 6–35.4% of patients during ECMO therapy [3,4,5].

Causes of intracranial hemorrhage in ECMO patients may be associated with heparin overdose, circuit-associated defibrination, thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acquired von Willebrand syndrome, and also COVID-19-associated endotheliitis. Importantly, intracranial hemorrhage was observed in many patients receiving VV-ECMO without coagulopathy or anticoagulant use [6].

In this respect, we analyzed preliminary data from the German COVID-19 Autopsy Registry [7], involving 63 deceased COVID-19 patients who received ECMO for acute respiratory failure. Specifically, we address the following questions, comparing COVID-19 autopsy cases that received ECMO support with cases that did not:

-

1.

What differences in demographical characteristics exist?

-

2.

What are the prevalences of bleeding events, specifically intracranial bleeding events found at autopsy?

Patient inclusion, data acquisition and management, and cohort stratification were performed as previously described [8] and are provided in the Additional file 1.

For analyses, N = 1129 autopsy cases with positive COVID-19 test (preclinical, clinical, or post-mortem, point of care antigen test from nasopharyngeal or pulmonary swabs or PCR test from nasopharyngeal or pulmonary swabs or tissue samples) were eligible in the German COVID-19 Autopsy Registry (DeRegCOVID). 20–22% of the COVID-19 autopsy cases were located in the East and West, respectively and 28–30% in the North and South of Germany, respectively by patient residential region (Fig. 1a) or by the autopsy center region (Fig. 1b), respectively.

a Number of COVID-19 autopsy cases and percentage of COVID-19 autopsies after ECMO therapy by postal code of the deceased person (1 value missing of ECMO cases, 17 values missing of non-ECMO cases). b Number of COVID-19 autopsy cases and percentage of COVID-19 autopsies after ECMO therapy by postal code of the contributing center. c Individual disease duration (orange bars) or death date (black boxes, when no data on symptom onset/ first positive SARS-CoV-2 test was available) in N = 63 ECMO COVID-19 autopsy cases. d Age and sex distribution in COVID-19 autopsies after ECMO therapy (N = 63). e Age and sex distribution in COVID-19 autopsies without ECMO therapy (N = 1065, 1 value missing). f Age and sex distribution in COVID-19 autopsies as a percentage of respective age group. g Intracranial bleeding (ICB) and other hemorrhages in ECMO and non-ECMO COVID-19 cases. The associations between the variables ECMO and ICB and ECMO and any bleeding event were significant (both p value < 0.0001 Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed). Note that the number of bleeding events exceeds the number of patients, because in N = 3 non-ECMO, and N = 3 ECMO autopsies, both ICB and other bleeding events were present at the autopsy, respectively. h ECMO cases (violet) and non-ECMO cases (dark yellow) with any bleeding event. The number of extracranial bleeding events is higher compared to h, because, in N = 4 ECMO cases, two different extracranial bleeding events were documented. ICB, intracranial bleeding

The percentage of COVID-19 ECMO autopsy cases of all autopsied cases increased with each pandemic wave, from 2% in the first pandemic wave to 6% in the second and 12% in the third wave (Fig. 1c).

N = 63 patients underwent ECMO therapy. The male to female ratio in this cohort was 5:1 with a homogeneous distribution of females over the different age range of < 30–80 years, and a male peak in the age range of 51–70 years (Fig. 1d). Of the remaining N = 1065 COVID-19 non-ECMO autopsy cases (one value missing), the male to female ratio was 2:1, with male peaks at 61–90 years and female predominance at > 90 years of age (Fig. 1e). The percentage of COVID-19 ECMO autopsy cases in the respective sex/age group was higher for males compared to females, however, in the younger age groups, total numbers were relatively low, resulting in large effects of single cases on the percentage (Fig. 1f).

Any kind of a bleeding event was found in 56% of ECMO cases (N = 35 cases) and 9% of non-ECMO cases (N = 100 cases, p value < 0.0001). Intracranial bleeding (ICB) was documented in N = 13 ECMO cases (21%) and in N = 30 non-ECMO cases (3%, p value < 0.0001, Fig. 1g). In ECMO patients with ICB, in three cases (N = 2 soft tissue bleeding due to cannulation and N = 1 epistaxis) and in non-ECMO patients with ICB, in three cases extracranial bleeding events were documented, respectively (N = 2 acute posthemorrhagic anemia not otherwise specified and N = 1 recurrent bleeding of the lower gastrointestinal tract, a detailed specification of bleeding events is provided in Fig. 1h). In 78% of ECMO cases and 37% of non-ECMO cases with ICB, the intracranial bleeding was classified as the immediate or underlying cause of death. The five most common immediate causes of death were multi-organ failure, DAD/ARDS, ICB, pulmonary bacterial ± fungal superinfection and extracranial bleeding events in N = 63 ECMO cases and DAD/ARDS, multi-organ failure, pulmonary bacterial ± fungal superinfection, pulmonary embolism, and ischemic heart disease in N = 1031 non-ECMO cases with the complete cause of death data (ordered by descending frequency).

VV-ECMO used in refractory severe acute respiratory failure is associated with an increased risk of bleeding, of which intracranial hemorrhage has been consistently associated with very poor survival. In this report, we analyzed data from the German Registry of COVID-19 Autopsies (DeRegCOVID) to gain further insights into COVID-19 ECMO autopsy cases with bleeding events in comparison to non-ECMO cases.

ECMO being more often documented in younger and male patients, is in line with data from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry [3].

The prevalence of any bleeding event in more than 50% of COVID-19 ECMO autopsy cases is higher compared to a previous multicenter observational study of 152 consecutive non-autopsy patients with severe COVID-19 supported by ECMO in four UK commissioned centers during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (30.9% major bleedings) [9]. This might be explained by our cohort consisting of fatal cases, which may lead to an overrepresentation of cases with bleeding events. Also, all macroscopically identified bleeding events are documented, irrespective of major bleeding criteria [10], as these data are usually not available at autopsy. Our findings regarding the prevalence of intracranial bleeding and associated mortality are consistent with a report from three tertiary care ECMO centers in Germany and Switzerland [11]. In an observational study from Northern Germany, the observation of intracranial bleeding in COVID-19 non-autopsy ECMO patients (35.4%) was higher compared to our findings. In a study from a single tertiary center on 25 non-COVID ECMO autopsy cases, 52% had intracranial macrohemorrhages [12]. However, it is possible, that due to concerns regarding occupational hazards, the omission of brain examination especially during the first pandemic wave led to an underreporting of intracranial hemorrhage at autopsy in our cohort.

Limitations

The registry only gathers data available to pathologists at the time of autopsy. The clinical information provided during autopsies is usually comprehensive, particularly regarding treatment approaches such as ECMO. Still, we cannot exclude missing data in the registry on potential ECMO therapy. Another limitation is the missing specific data on invasive ventilation therapy and missing reliable data on the mode and time of anticoagulant therapy in our cohort. Because we aimed at the broadest possible participation in the registry, the eCRF does not cover therapy and intensive care details and duration of ventilation or ECMO therapy. Considering that in more than 50% of our cohort, the immediate cause of death at autopsy was COVID-19 DAD/ARDS, it is likely that some of these patients underwent invasive ventilation therapy before death in hospitalized cases [8].

In conclusion, our report showed autopsy-confirmed increased prevalence of bleeding events and intracranial hemorrhages as causes of death in COVID-19 patients with ECMO treatment, compared to those without ECMO treatment. This illustrates the value of autopsies and a joint interdisciplinary multicenter (national) approach in addressing fatal complications in intensive care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DAD:

-

Diffuse alveolar damage

- DeRegCOVID:

-

German COVID-19 Autopsy Registry

- eCRF:

-

Electronic case report form

- ELSO:

-

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization

- ICB:

-

Intracranial bleeding

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RWTH Aachen University:

-

Rhenish-Westphalian Technical University Aachen

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- VV-ECMO:

-

Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

References

Friedrichson B, Mutlak H, Zacharowski K, Piekarski F. Insight into ECMO, mortality and ARDS: a nationwide analysis of 45,647 ECMO runs. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):38.

Nunez JI, Gosling AF, O’Gara B, Kennedy KF, Rycus P, Abrams D, Brodie D, Shaefi S, Garan AR, Grandin EW. Bleeding and thrombotic events in adults supported with venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an ELSO registry analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(2):213–24.

Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, Iwashyna TJ, Slutsky AS, Fan E, Bartlett RH, Tonna JE, Hyslop R, Fanning JJ, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1071–8.

Lebreton G, Schmidt M, Ponnaiah M, Folliguet T, Para M, Guihaire J, Lansac E, Sage E, Cholley B, Megarbane B, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation network organisation and clinical outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greater Paris, France: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(8):851–62.

Pantel T, Roedl K, Jarczak D, Yu Y, Frings DP, Sensen B, Pinnschmidt H, Bernhardt A, Cheng B, Lettow I, et al. Association of COVID-19 with intracranial hemorrhage during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 10-year retrospective observational study. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):28.

Schmidt M, Chommeloux J, Frere C, Hekimian G, Combes A. Overcoming bleeding events related to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in COVID-19 - Authors' reply. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(12):e89.

von Stillfried S, Bulow RD, Rohrig R, Knuchel-Clarke R, Boor P. DeRegCovid: autopsy registry can facilitate COVID-19 research. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(8):e12885.

von Stillfried S, Bulow RD, Röhrig R, Boor P. First report from the German COVID-19 autopsy registry. Lancet Reg Health - Europe. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100330.

Arachchillage DJ, Rajakaruna I, Scott I, Gaspar M, Odho Z, Banya W, Vlachou A, Isgro G, Cagova L, Wade J, et al. Impact of major bleeding and thrombosis on 180-day survival in patients with severe COVID-19 supported with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the United Kingdom: a multicentre observational study. Br J Haematol. 2022;196(3):566–76.

Schulman S, Kearon C. Subcommittee on control of anticoagulation of the S, Standardization Committee of the International Society on T, haemostasis: definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692–4.

Seeliger B, Doebler M, Hofmaenner DA, Wendel-Garcia PD, Schuepbach RA, Schmidt JJ, Welte T, Hoeper MM, Gillmann HJ, Kuehn C, et al. Intracranial hemorrhages on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: differences between COVID-19 and other viral acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2022.

Hwang J, Caturegli G, White B, Chen L, Cho SM. Cerebral microbleeds and intracranial hemorrhages in adult patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-autopsy study. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(3):e0358.

German COVID-19 autopsy registry. German. https://www.drks.de/drks_web/navigate.do?navigationId=trial.HTML&TRIAL_ID=DRKS00025136.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

#DeRegCOVID collaborators: Jana Böcker4, Jens Schmidt4, Pauline Tholen4, Raphael Majeed5, Jan Wienströer5, Joachim Weis6, Juliane Bremer6, Ruth Knüchel7, Anna Breitbach7, Claudio Cacchi7, Benita Freeborn7, Sophie Wucherpfennig7, Oliver Spring8, Georg Braun9, Christoph Römmele9, Bruno Märkl10, Rainer Claus10, Christine Dhillon10, Tina Schaller10, Eva Sipos10, Klaus Hirschbühl11, Michael Wittmann11, Elisabeth Kling12, Thomas Kröncke13, Frank L. Heppner14,15,16, Jenny Meinhardt14, Helena Radbruch14, Simon Streit14, David Horst17, Sefer Elezkurtaj17, Alexander Quaas18, Heike Göbel18, Torsten Hansen19, Ulf Titze19, Johann Lorenzen20, Thomas Reuter20, Jaroslaw Woloszyn20, Gustavo Baretton21, Julia Hilsenbeck21, Matthias Meinhardt21, Jessica Pablik21, Linna Sommer21, Olaf Holotiuk22, Meike Meinel22, Nina Mahlke23, Irene Esposito24, Graziano Crudele24, Maximilian Seidl24, Kerstin U. Amann25, Roland Coras26, Arndt Hartmann27, Philip Eichhorn27, Florian Haller27, Fabienne Lange27, Kurt Werner Schmid28, Marc Ingenwerth28, Josefine Rawitzer28, Dirk Theegarten28, Christoph G. Birngruber29, Peter Wild30, Elise Gradhand30, Kevin Smith30, Martin Werner31, Oliver Schilling31, Till Acker32, Stefan Gattenlöhner33, Christine Stadelmann34, Imke Metz34, Jonas Franz34, Lidia Stork34, Carolina Thomas34, Sabrina Zechel34, Philipp Ströbel35, Claudia Wickenhauser36, Christine Fathke36, Anja Harder36, Benjamin Ondruschka37, Eric Dietz37, Carolin Edler37, Antonia Fitzek37, Daniela Fröb37, Axel Heinemann37, Fabian Heinrich37, Anke Klein37, Inga Kniep37, Larissa Lohner37, Dustin Möbius37, Klaus Püschel37, Julia Schädler37, Ann-Sophie Schröder37, Jan-Peter Sperhake37, Martin Aepfelbacher38, Nicole Fischer38, Marc Lütgehetmann38, Susanne Pfefferle38, Markus Glatzel39, Susanne Krasemann39, Jakob Matschke39, Danny Jonigk40, Christopher Werlein40, Peter Schirmacher41, Lisa Maria Domke41, Laura Hartmann41, Isabel Madeleine Klein41, Constantin Schwab41, Christoph Röcken42, Johannes Friemann43, Dorothea Langer44, Wilfried Roth45, Stephanie Strobl45, Martina Rudelius46, Konrad Friedrich Stock47, Wilko Weichert48, Claire Delbridge48, Atsuko Kasajima48, Peer-Hendrik Kuhn48, Julia Slotta-Huspenina48, Gregor Weirich48, Peter Barth49, Eva Wardelmann49, Alexander Schnepper49, Katja Evert50, Andreas Büttner51, Johannes Manhart51, Stefan Nigbur51, Iris Bittmann52, Falko Fend53, Hans Bösmüller53, Massimo Granai53, Karin Klingel53, Verena Warm53, Konrad Steinestel54, Vincent Gottfried Umathum54, Andreas Rosenwald55, Florian Kurz55, Niklas Vogt55

4Center for Translational & Clinical Research (CTC-A), University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany; 5Institute for Medical Informatics, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany; 6Institute of Neuropathology, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany; 7Institute of Pathology, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany; 8Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, University Hospital Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; 9Gastroenterology, University Hospital Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; 10General Pathology and Molecular Diagnostics, University Hospital Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; 11Hematology and Oncology, University Hospital Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; 12Laboratory Medicine and Microbiology, University Hospital Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; 13Radiology, University Hospital Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany; 14Department of Neuropathology, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 15German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 16Cluster of Excellence, NeuroCure, Berlin, Germany; 17Institute of Pathology, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 18Department of Pathology, University Hospital Cologne, Cologne, Germany; 19Institute of Pathology, University Hospital OWL of the Bielefeld University, Campus Lippe, Detmold, Germany; 20Department of Pathology, Klinikum Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany; 21Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Dresden, Dresden, Germany; 22Gemeinschaftspraxis für Pathologie, Dresden, Germany; 23Institute of Forensic Medicine, University Hospital Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany; 24Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany; 25Department of Nephropathology, University Hospital Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany; 26Institute of Neuropathology, University Hospital Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany; 27Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany; 28Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany; 29Institute of Forensic Medicine, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany; 30Senckenberg Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany; 31Institute for Surgical Pathology, Medical Center-University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; 32Institute of Neuropathology, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Giessen, Germany; 33Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Giessen, Germany; 34Institute of Neuropathology, University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany; 35Institute of Pathology, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany; 36Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Halle (Saale), Halle (Saale), Germany; 37Institute of Legal Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg- Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; 38Institute of Medical Microbiology, Virology, and Hygiene, University Medical Center Hamburg- Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; 39Institute of Neuropathology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; 40Institute of Pathology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany; 41Institute of Pathology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany; 42Department of Pathology, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, Germany; 43Department of Pathology, University Hospital Cologne, Lüdenscheid, Germany; 44Institute of Pathology, Klinikum Magdeburg, Magdeburg, Germany; 45Institute of Pathology, University Medical Center Mainz, Mainz, Germany; 46Institute of Pathology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, Munich, Germany; 47Department of Nephrology, TUM School of Medicine of Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany; 48Institute of Pathology, TUM School of Medicine of Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany; 49Gerhard Domagk Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany; 50Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany; 51Rostock University Medical Center, University Hospital Rostock, Rostock, Germany; 52Institute of Pathology, Agaplesion Diakonieklinikum Rotenburg, Rotenburg, Germany; 53Institute of Pathology and Neuropathology, University Hospital Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany; 54Department of Pathology, Bundeswehrkrankenhaus Ulm, Ulm, Germany; 55Institute of Pathology, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the German Registry of COVID-19 Autopsies (www.DeRegCOVID.ukaachen.de), funded Federal Ministry of Health (ZMVI1-2520COR201), by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the framework of the network of university medicine (DEFEAT PANDEMIcs, 01KX2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Drs SVS and PB had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data, which were provided by the study collaborators, and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: SVS, RDB, RR, PB. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: SVS, RDB, RR, PB. Drafting of the manuscript: SVS, RDB, RR, PB. Obtained funding: Boor. Administrative, technical, or material support: SVS, RDB, RR, PB. Supervision: PB. All authors and collaborators approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Only cases with a consent given by the deceased or next of kin for autopsy or request for autopsy by the health authorities or by the prosecutor’s office were included in the registry. The registry was approved by the ethical committee of the medical faculty of the RWTH Aachen University (EK 092/20). Additionally, each participating center had a local ethical approval. The registry was registered with the German Clinical Trials Registry [13].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Methods and Discussion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

von Stillfried, S., Bülow, R.D., Röhrig, R. et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in COVID-19 patients during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory failure: a nationwide register study report. Crit Care 26, 83 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03945-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03945-x