Abstract

This paper documents and analyzes the alternations between glides and fricatives in Atayal, an endangered Austronesian language spoken in northern Taiwan. Distributional gaps and morphophonological alternations suggest that onset glides in the Jianshi variety of Squliq Atayal do not appear before a schwa or a homorganic vowel. The paper argues that the restrictions on onset glides are motivated by the needs to achieve an optimal sonority profile within a syllable and to avoid homorganic glide-vowel sequences. In the proposed OT account, sonority dispersion and similarity avoidance are formalized as separate constraints, which is supported by the attested typology across Atayal dialects. The strengthening data justify the placement of schwa lower in the sonority hierarchy than high vowels, and the adopted conjoined constraints further suggest that sonority-based co-occurrence restrictions are not necessarily restricted to syllable margins (cf. Steriade in Language 64:118–129, 1988a). The paper also shows that (1) the behavior of j and w is asymmetrical in some dialects, with w combining more freely with the following nucleus vowel than j does; and (2) Atayal phonemic /w/ primarily alternates with velar [ɣ], which is peculiar among Formosan languages. The fact that Atayal consonantal w strengthens to velar [ɣ] instead of a labial falsifies the feature theories in which /w/ is characterized only by the [Labial] articulator (Halle et al. in Linguist Inq 31:387–444, 2000; Halle in Linguist Inq 36: 23–41, 2005; Levi in The representation of underlying glides: a cross-linguistic study, 2004; Lingua 118:1956–1978, 2008).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The figure is based on the monthly demographic data (as of October 2019) provided by the Council of Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan. Speakers who can speak the language fluently, however, are mostly above the age of 50.

The reconstructed *y presumably stands for a palatal glide. Li (1974) attempts to identify the phonetic values of the Pan phonemes *j and *v as reconstructed by Dempwolff, and *y and *w as reconstructed by Dyen; he concludes that the direction of changes is from semi-consonants to fricatives or liquids. The reconstructed symbol *y from the original sources is retained here without modification.

Although the term Mayrinax has been widely used in the literature so far, the present study adopts the endonym Matu’uwal preferred by the consultants, rather than the exonym Mayrinax.

The Sqoyaw data are from Yamada and Liao (1974) and Liao (2014); all the other data are based on the author’s fieldwork unless noted otherwise. Some of the Jianshi Squliq data are from the online dictionary (https://e-dictionary.apc.gov.tw/tay/Search.htm) maintained by the Council of Indigenous Peoples, Taiwan, R.O.C.

The six dialects are commonly referred to as Squliq (distributed in all seven counties/cities; see the map below), Matu’uwal (often by the name Mayrinax in the literature so far), Skikun (in Tatung Township of Yilan County), Plngawan (in Ren’ai Township of Nantou County), C’uli’ in Yilan (including Pyahaw), and C’uli’ (in other areas than Yilan, including Hsinchu, Miaoli, Taichung, and Nantou).

The Squliq data for the present study include the Mrqwang variety of Jianshi Squliq, the R’uyan variety of Taoshan Squliq, and Sqoyaw in Taichung. The terms Jianshi and Taoshan refer to the names of the townships (administrative divisions) where the dialects are spoken, and they are commonly used in the Atayal literature. Mrqwang, R’uyan, Sqoyaw (and Pyasan, of Fuhsing Squliq) are the traditional terms for the clans/tribes or the places.

Some postconsonantal prenuclear glides are phonemic due to an optional rule that deletes the vowel preceding the onset glide of the penultimate syllable, followed by resyllabification (Huang 2014:819). Vocalic glides do not occur syllable-initially.

The main point here is that the expected schwa becomes homorganic to the preceding sibilant. Atayal consultants indicate that the pronunciations of [sɿ] and [ʦɿ] resemble the Mandarin spoken in Taiwan (which does not have *[zɿ]), while Mandarin corresponding sounds are reported in Lee-Kim (2014), based on Beijing Mandarin, to be syllabic approximants without frication noise rather than syllabic fricatives or apical vowels. The symbol [ɿ] is used here to represent the articulation of the syllabic element, and its phonetics awaits future research.

Onset glides may be optionally strengthened to fricatives before /u a/ vowels; see more discussion in Sect. 6.

The data in this paper include the following affixes: -an, lv; -un, pv; -i, pv/lv.at;-aj, lv.proj; -anaj, cv.proj; -a, av.proj; m-/mə-/<əm>, av; p-/pə-, caus;k-/kə-, stat; <in>/<ən>, pfv. The abbreviations used are as follows: av, Agent Voice; lv, Locative Voice; pv, Patient Voice; cv, Circumstantial Voice; at, Atemporal; proj, Projective; pfv, Perfective; nom, Nominative; gen, Genitive; caus, Causative; stat, Stative; sg, Singular. Angled brackets < > indicate surface infixes and a tilde connects the reduplicant and the stem, following Leipzig Glossing Rules.

There are constraints on the combination of stems and suffixes for morphosyntactic or semantic reasons, so forms with other suffixes (i.e /-aj/ ‘lv.proj’ here) will be provided when an-suffixed forms are not available to illustrate the environment before a low vowel.

One might argue that the root contains the underlying form /ћŋaw/, which contains a consonant cluster. It is assumed here that an empty vowel slot (‘V’) is present in the penultimate position (see related discussion in Huang (2018)). These alternatives do not bear on the main points of the data here.

The historical development of the irrealis usage of un-forms in Atayal has not received a full treatment in the literature, and it remains unclear at what stage such an innovation has emerged. If the usage developed at an early stage in Atayal, it would be Taoshan Squliq that underwent further reduction. The main point of the proposed analysis remains unaffected, though: stem-final w is observed to strengthen to ɣ when it precedes the vowel u. See Yeh (2013) for more discussion on the distinctions between un- and an-forms in both Wulai Squliq and Jianshi Squliq, citing Huang (1993).

The syllable boundaries in the data are meant to indicate the presence of derived diphthongs such as ia in (5a) [zɿ.ŋian], iu in (5b) [pə.zɿ.ŋiun], and ua in (5d) [ћə.ɣə.ruan]. For the insertion of word-final glottal stops (e.g. (5a) [ju.ŋiʔ]), see Huang (2015b).

The two scales are compatible with most works on sonority hierarchy, although they are not as fine-grained as, e.g., the scales in Parker (2002). The two hierarchies given here omit the constraints against the presence of vocalic elements in onset and consonantal elements in peak position, such as *O/a and *P/t, which are of course higher ranked than any of the constraints given in the hierarchies under discussion.

Matu’uwal mə/ma- and um correspond to Squliq m-/-m- (av), respectively; pa- corresponds to p-(caus). Please refer to Note 10.

Matu’uwal is a conservative Atayal dialect and preserves the distinction between male and female forms of speech (Li 1982).

A minor pattern in the antepenultimate position is that the empty vowels harmonize to the vowels to their right; this seems to be subject to inter-speaker variation.

The underlying forms of the roots are inferred by the author rather than provided by Liao. Liao (2014) does not use the phonetic symbol [ʑ] in his dictionary. Sounds transcribed as [ʑi] in (20) are represented by zi in the dictionary and transcribed as [zi] (Liao 2014:VIII). The narrow transcriptions here are based on Yamada and Liao (1974:111), where it is remarked that the z sound is [ʑ] in IPA, occurring only before /i/.

The only exception of ji in the dictionary is the occurrence of [təwaji] (ordinarily [təwaʑ-i]) ‘cook without mixing other types of food; drink without eating’ (Liao 2014:1631). There are some variations in the dictionary, too. For example, at least 37 instances of the word ‘forget’ [jəŋijan] (/juŋi, an/) can be identified in the dictionary, with jə, but the exceptional [zəŋijan] is found only once (p. 1247).

It seems that the root /tiwaya/ can be further decomposed into separate morphemes, but its morphological composition calls for more research. Moreover, it is unclear whether the underlying form is /tiwaya/ or /ʦiwaya/ because both /t/ and /ʦ/ (as well as /s/ and z) palatalize before /i/.

The Sqoyaw form (23c) [k-i-təsaw-an] presumably involves dropping the coda n of the surface infix in (‘pfv’), a rule not found in Jianshi or Taoshan Squliq. The root-initial consonant of (23c) varies between t~ʦ.

Both (24e–f) contain the derivational prefix t- preceding the root /ʔaβaw/ ‘leaf’ in (24e) and /sasaw/ ‘shadow, shade’ in (24f). The forms [ʦəsaw-an] and [ʦəsaw-un] have variants [təsaw-an] and [təsaw-un], respectively.

Seventeen of the nineteen consultants had passed away when the dictionary was published (Liao 2014:III).

The example [pə-təqajaw-un] in (24d) contains an unreduced antepenultimate vowel [a], which appears to be a typo in the original source.

Some in-affixed forms are not affected by the prepenultimate reduction rule in both Jianshi and Taoshan Squliq.

The word illustrates the rule of /ɣ/ → [w] / ___#. See Sect. 6 for more details.

Also see Baertsch (2012) and the references cited therein for more work on a sonority distinction between front and back vowels/glides.

The orthographic symbols b, g, y, and h in Li (1980) are changed to the corresponding IPA symbols β, ɣ, j, and ħ here.

Sqoyaw [maɣ-an], [maɣ-un], [maɣ-i] involves the dropping of unstressed syllables (here, ʔi) toward the left edge, which is also a common process in Jianshi Squliq, Fuhsing Squliq, and especially in Wulai Squliq.

It is controversial whether words such as [maʑij] and [maħij] contain a word-final glide homorganic to the preceding vowel. Egerod (1980) transcribes Li’s stem-final ij as ii (and uw as uu). If stem-final ij and uw are well-formed, the proposed OCPsim constraint will need to be restricted to initial demisyllables.

IPA transcriptions are not provided for the suffixed forms with -un and -an here because it is not clear from the original descriptions as to whether the z is alveolar or alveolo-palatal. In an- and un-suffixed forms, the realization of the surface stem-final fricatives in Taoshan Squliq is always [ʑ].

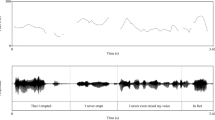

The texts (approximately 1000 words) and audio files are from the website http://ilrdc.tw/grammar/index.php?l=2&p=19, which accompany the reference grammar by Huang and Hayung (2018). The corresponding glossing of the text material can be found in Appendix III of the book (in Chinese).

It happens that in the two texts there is no syllable-initial phonemic w followed by i, so it cannot be determined whether strengthening would affect wi sequences.

Another point worth mentioning in Li’s (1974) study is concerned with the conditioning environments where strengthening takes place in Tanan Rukai. Li (ibid.) gives the rules of j → ð / __+a and w → v / __ +a, showing that strengthening takes place only before low vowels across morpheme boundaries, but not before high vowels, which is contrary to the proposed phonetically based motivations of Squliq Atayal glide strengthening. More research is needed to shed light on the nature of the Rukai data.

Li (1974:171) specifies that the Atayal reflex for Pan *w is w in both non-final and final positions; the Atayal data in his study do not contain words with onset w preceding weak vowels, however.

Jacobs and van Gerwen (2006:82) state that the Spanish reflexes of Germanic [w] are labiovelar [gw] or [ɣw] besides the delabialized [g] or [ɣ], but summarizes that the reflexes are [g]/[gw]~[ɣw]/[w] in the introduction (Jacobs and van Gerwen 2006:78). The paper adopts the former statements and considers the latter ones as typing mistakes.

The pronunciation [wǝ.riuŋ] can also be found in Taoshan Squliq.

In the speech of a less conservative Taoshan Squliq speaker, the affixed forms of /wajaɣ/ ‘choose’ (see the data in (26b)) are found to contain a β variant: /wajaɣ, i/ [βǝjaɣi] and /in, wajaɣ, an/ [βin.ja.ɣan]; however, this is the only example involving synchronic w~β alternations that have been identified in my fieldwork on Taoshan Squliq.

This is also due to the fact that unstressed syllables farther away from the right edge are more likely to drop in Jianshi Squliq, so it is more difficult to find relevant data showing how pretonic wǝ alternates.

References

Baertsch, Karen. 1998. Onset sonority distance constraints through local conjunction. In CLS 34: The Panels (The Proceedings from the Panels of the Chicago Linguistic Society’s Thirty-Fourth Meeting), vol. 34-2, ed. M. Catherine Gruber, Derrick Higgins, Kenneth S. Olson, and Tamra Wysocki, 1–15. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Baertsch, Karen. 2008. Asymmetrical glide patterns in American English: The resolution of CiV vs. CuV sequences. Language Research 44: 223–240.

Baertsch, Karen. 2012. Sonority and sonority-based relationships within American English monosyllabic words. In The Sonority Controversy, ed. Steve Parker, 3–37. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Bernhardt, Barbara H., and Joseph P. Stemberger. 1998. Handbook of Phonological Development: From the Perspective of Constraint-Based Nonlinear Phonology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Blust, Robert. 1990. Patterns of sound change in the Austronesian languages. In Philip Baldi, ed. Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology, 231–267. Berlin; New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

Blust, Robert. 1994. Obstruent epenthesis and the unity of phonological features. Lingua 93: 111–139.

Blust, Robert. 2013. The Austronesian Languages, Revised edition. Canberra ACT: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Bradley, Travis G., and Jacob J. Adams. 2018. Sonority distance and similarity avoidance effects in Moroccan Judeo-Spanish. Linguistics 56: 1463–1511.

Browman, Catherine P., and Louis Goldstein. 1992. Articulatory phonology: An overview. Phonetica 49: 155–180.

Chen, Kang, and Zhong Lin. 1985. Taiwan gaoshanzu Taiyeeryu gaikuang [A brief description of Atayal spoken by gaoshan nationality in Taiwan]. Minzu Yuwen 5: 68–80. (In Chinese).

Chen, Yi-Jie Joyce. 2012. Affixation Induced Phonological Variation in Plngawan Atayal. MA thesis, National Tsing Hua University.

Chen, Yin-Ling C. 2011. Issues in the Phonology of Ilan Atayal. Ph.D. dissertation, National Tsing Hua University.

Cheng, Ju Chang. 2001. A Phonological Perspective of Phonetic Symbolic System of Atayal: The Case of Tausa [Cong Yinyunxue de Jiaodu Kan Taiyayu de Biaoyin Xitong: Yi Taoshan Fangyan Weili]. MA thesis, National Hsinchu Teachers’ College. (In Chinese)

Chung, Raung-fu. 1991. On [V] initials in Hakka [Lun Kejiahua de V shengmu]. Chinese Phonology 3: 435–455.

Clements, George N. 1988. The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabification. Working Papers of the Cornell Phonetics Laboratory 2: 1–68.

Clements, George N. 1990. The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabification. In Laboratory Phonology I: Between the Grammar and Physics of Speech, ed. John Kingston and Mary E. Beckman, 283–333. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clements, George N., and Elizabeth V. Hume. 1995. The internal organization of speech sounds. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory, ed. John A. Goldsmith, 245–306. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Davis, Stuart, and Michael Hammond. 1995. On the status of onglides in American English. Phonology 12: 159–182.

de Carvalho, Joaquim Brandão, Tobias Scheer, and Philippe Ségéral. 2008. Introduction to the volume. In Lenition and Fortition, ed. Joaquim Brandão de Carvalho, Tobias Scheer, and Philippe Ségéral, 1–8. Berlin; New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

de Lacy, Paul V. 2002. The Formal Expression of Markedness. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

de Lacy, Paul. 2004. Markedness conflation in optimality theory. Phonology 21: 145–199.

de Lacy, Paul. 2006. Markedness: Reduction and Preservation in Phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Lacy, Paul. 2010. Review of Dresher (2009). Phonology 27: 532–536.

Dresher, B.Elan. 2009. The Contrastive Hierarchy in Phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Egerod, Søren. 1965a. Verb inflexion in Atayal. Lingua 15: 251–282.

Egerod, Søren. 1965b. An Atayal-English vocabulary. Acta Orientalia 29: 203–220.

Egerod, Søren. 1966. A statement on Atayal phonology. Artibus Asiae Supplementum XXIII (Felicitation Volume for the 75th Birthday of Prof. G.H. Luce) 1: 120–130.

Egerod, Søren. 1980. Atayal-English Dictionary. Scandinavian Institute of Asian Studies Monograph Series No. 35. London and Malmö: Curzon Press.

Egerod, Søren. 1999. Atayal-English Dictionary, 2nd edition, ed. Jens Østergaard Petersen. Copenhagen: The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters.

Gick, Bryan. 2003. Articulatory correlates of ambisyllabicity in English glides and liquids. In Phonetic Interpretation: Papers in Laboratory Phonology VI, ed. John Local, Richard Ogden, and Rosalind Temple, 222–236. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon, Matthew, Edita Ghushchyan, Bradley McDonnell, Daisy Rosenblum, and Patricia A. Shaw. 2012. Sonority and central vowels: A cross-linguistic phonetic study. In The Sonority Controversy, ed. Steve Parker, 219–256. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Gordon, Matthew Kelly. 2016. Phonological Typology. Oxford Surveys in Phonology and Phonetics 1. New York: Oxford University Press.

Halle, Morris. 2005. Palatalization/velar softening: What it is and what it tells us about the nature of Language. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 23–41.

Halle, Morris, Bert Vaux, and Andrew Wolfe. 2000. On feature spreading and the representation of place of articulation. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 387–444.

Henke, Eric, Ellen M. Kaisse, and Richard Wright. 2012. Is the sonority sequencing principle an epiphenomenon? In The Sonority Controversy. Phonology and Phonetics 18, ed. Steve Parker, 65–100. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Ho, Dah-an. 1978. A preliminary comparative study of five Paiwan dialects. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 49: 565–681.

Hsu, Hui-Chuan. 2003. A sonority model of syllable contraction in Taiwanese Southern Min. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 12: 349–377.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2006a. Resolving vowel clusters: A comparison of Isbukun Bunun and Squliq Atayal. Language and Linguistics 7: 1–26.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2006b. Squliq Atayal syllable onset: Simple or complex? In Streams Converging into an Ocean: Festschrift in Honor of Professor Paul Jen-kuei Li on his 70th Birthday, ed. Henry Y. Chang, Lillian M. Huang, and Dah-an Ho, 489–505. Taipei, Taiwan: Academia Sinica.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2014. Phonological patterning of prevocalic glides in Squliq Atayal. Language and Linguistics 15: 801–823.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2015a. The phonemic status of /z/ in Squliq Atayal revisited. In Capturing Phonological Shades Within and Across Languages, ed. Yuchau E. Hsiao and Lian-Hee Wee, 243–265. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2015b. Syllable types in Bunun, Saisiyat, and Atayal. In New Advances in Formosan Linguistics, ed. Elizabeth Zeitoun, Stacy F. Teng, and Joy J. Wu, 47–74. Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2017. Matu’uwal (Mayrinax) vowel syncope. Poster presented at The 14th Old World Conference on Phonology, Dusseldorf, Germany, 20–22 February.

Huang, Hui-chuan J. 2018. The nature of pretonic weak vowels in Squliq Atayal. Oceanic Linguistics 57: 265–288.

Huang, Lillian M. 1993. A Study of Atayal Syntax. Taipei: Crane.

Huang, Lillian M. 1995. A Study of Mayrinax Syntax. Taipei: Crane.

Huang, Lillian M. 2000. Verb classification in Mayrinax Atayal. Oceanic Linguistics 39: 364–390.

Huang, Lillian M., and Tali’ Hayung. 2018. An Introduction to Atayal Grammar [Taiyayu Yufa Gailun], 2nd edition. Formosan Language Series, No. 2. New Taipei City: Council of Indigenous Peoples. (In Chinese)

Hume, Elizabeth V. 1992. Front Vowels, Coronal Consonants and Their Interaction in Nonlinear Phonology. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University.

Hunt, Elisabeth Hon. 2009. Acoustic Characterization of the Glides /j/ and /w/ in American English. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Itô, Junko, and Armin Mester. 1998. Markedness and word structure: OCP effects in Japanese. Unpublished ms., University of California, Santa Cruz (ROA-255).

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2003. Japanese Morphophonemics: Markedness and Word Structure. Cambridge, MA, London: MIT Press.

Jacobs, Haike, and Robbie Van Gerwen. 2006. Glide strengthening in French and Spanish and the formal representation of affricates. In Historical Romance Linguistics: Retrospective and Perspectives, ed. Randall S. Gess and Deborah L. Arteaga, 77–95. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Jaggers, Zachary S. 2018. Evidence and characterization of a glide-vowel distinction in American English. Laboratory Phonology: Journal of the Association for Laboratory Phonology 9: 1–27.

Johnson, Keith. 2012. Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics, 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Willey-Blackwell.

Kawasaki, Haruo. 1982. An Acoustical Basis for Universal Constraints on Sound Sequences Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Berkeley.

Kenstowicz, Michael. 1996. Quality-sensitive stress. Rivista di Linguistica 9: 157–187.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1979. Metrical structure assignment is cyclic. Linguistic Inquiry 10: 421–441.

Lambert, Wendy Mae. 1999. Epenthesis, Metathesis, and Vowel-Glide Alternation: Prosodic Reflexes in Mabalay Atayal. MA thesis, National Tsing Hua University.

Lavoie, Lisa M. 2001. Consonant Strength: Phonological Patterns and Phonetic Manifestations. New York, London: Garland Publishing.

Lee, Amy Pei-jung. 2012. The segment/w/and contrastive hierarchy in Paiwan and Seediq. Concentric: Studies in Linguistics 38 (1): 1–37.

Lee-Kim, Sang-Im. 2014. Revisiting Mandarin ‘apical vowels’: An articulatory and acoustic study. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 44 (3): 261–282.

Levi, Susannah V. 2004. The Representation of Underlying Glides: A Cross-Linguistic Study. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington.

Levi, Susannah V. 2008. Phonemic vs. derived glides. Lingua 118: 1956–1978.

Levin, Juliette. 1985. A Metrical Theory of Syllabicity. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1974. Alternations between semi-consonants and fricatives or liquids. Oceanic Linguistics 13: 163–186.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1977. Morphophonemic alternations in Formosan languages. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 48: 375–413.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1980. The phonological rules of Atayal dialects. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 51: 349–405.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1981. Reconstruction of Proto-Atayalic phonology. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 52: 235–301.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1982. Male and female forms of speech in the Atayalic group. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 53: 265–304.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1985a. The position of Atayal in the Austronesian family. In Austronesian Linguistics at the 15th Pacific Science Congress, Pacific Linguistics C-88, ed. Andrew Pawley and Lois Carrington, 257–280. Canberra: The Australian National University.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1985b. Linguistic criteria for classifying the Atayalic dialect groups. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 56: 699–718.

Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1995. The case-marking system in Mayrinax Atayal. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 66: 23–52.

Liao, Ying-chu. 2014. Tayal-Chinese Dictionary. Nantou, Taiwan: Liao, Ying-chu.

Lin, Hui-shan. 2015. Squliq Atayal reduplication: Bare consonant or full syllable copying? In New Advances in Formosan Linguistics, ed. Elizabeth Zeitoun, Stacy F. Teng, and Joy J. Wu, 75–100. Canberra ACT: Asia-Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Lin, Wan-Ying. 2004. Vowel Epenthesis and Reduplication in Squliq and C’uli’ Atayal Dialects. MA thesis, National Tsing Hua University.

Maddieson, Ian, and Karen Emmorey. 1985. Relationship between semivowels and vowels: Cross-linguistic investigations of acoustic difference and coarticulation. Phonetica 42: 163–174.

Marin, Stefania Nicoleta. 2007. Vowel to Vowel Coordination, Diphthongs and Articulatory Phonology. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University.

McCarthy, John J., and Alan Prince. 1995. Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers 18: Papers in Optimality Theory, ed. Jill Beckman, Laura Walsh Dickey, and Susan Urbanczyk, 249–384. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Murray, Robert W., and Theo Vennemann. 1983. Sound change and syllable structure in Germanic phonology. Language 59: 514–528.

Nevins, Andrew, and Ioana Chitoran. 2008. Phonological representations and the variable patterning of glides. Lingua 118: 1979–1997.

Ohala, Diane K. 1999. The influence of sonority on children’s cluster reductions. Journal of Communication Disorders 32: 397–422.

Padgett, J. 2008. Glides, vowels, and features. Lingua 118: 1937–1955.

Paradis, Carole. 1987. Glide alternations in Pulaar (Fula) and the theory of Charm and Government. In Current Approaches to African Linguistics, ed. David Odden, 327–338. Dordrecht, Holland: Foris Publications.

Parker, Steve. 2008. Sound level protrusions as physical correlates of sonority. Journal of Phonetics 36: 55–90.

Parker, Stephen G. 2002. Quantifying the Sonority Hierarchy. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Pons-Moll, C. 2011. It is all downhill from here: A typological study of the role of Syllable Contact in Romance languages. Probus 23: 105–173.

Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 1993/2004. Optimality Theory: Constraint Interaction in Generative Grammar. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing (2004). Technical Report, Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science and Computer Science Department, University of Colorado at Boulder (1993).

Rau, Der-Hwa Victoria. 1992. A Grammar of Atayal. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University. Published Taipei: Crane.

Ray, Sidney H. 1913. The languages of Borneo. SMJ (The Sarawak Museum Journal) 1 (4): 1–196.

Ségéral, Philippe, and Tobias Scheer. 2008. Positional factors in lenition and fortition. In Lenition and Fortition, ed. Tobias Scheer, Philippe Ségéral, and Joaquim Brandão de Carvalho, 131–172. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

Shih, Shu-hao. 2018a. On the existence of sonority-driven stress in Gujarati. Phonology 35: 327–364.

Shih, Shu-hao. 2018b. Non-Moraic Schwa: Phonology and Phonetics. Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers University.

Smith, Jennifer Lynn. 2002. Phonological Augmentation in Prominent Positions. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Smolensky, Paul. 1993. Harmony, markedness, and phonological activity. Handout to talk presented at Rutgers Optimality Workshop 1, 23 October, New Brunswick, N.J. [ROA-87, http://roa.rutgers.edu].

Steriade, Donca. 1982/1990. Greek Prosodies and the Nature of Syllabification. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT. New York: Garland Press.

Steriade, Donca. 1988a. Review of Clements and Keyser (1983). Language 64: 118–129.

Steriade, Donca. 1988b. Reduplication and syllable transfer in Sanskrit and elsewhere. Phonology 5: 73–155.

Uffmann, Christian. 2006. Epenthetic vowel quality in loanwords: Empirical and formal issues. Lingua 116: 1079–1111.

Vennemann, Theo. 1988. Preference Laws for Syllable Structure and the Explanation of Sound Change. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Wilbur, Ronnie B. 1973. The Phonology of Reduplication. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Yamada, Yukihiro, and Ying-chu Liao. 1974. A phonology of Atayal. Research Reports of the Kochi University 23 (6): 109–117.

Yeh, Maya Yuting. 2013. Event Conceptualization and Verb Classification in Squliq Atayal. Ph.D. dissertation, National Taiwan University.

Zeitoun, Elizabeth, and Chen-huei Wu. 2006. An overview of reduplication in Formosan languages. In Streams Converging into an Ocean: Festschrift in Honor of Professor Paul Jen-kuei Li on his 70th Birthday, ed. Henry Y. Chang, Lillian M. Huang, and Dah-an Ho, 97–142. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Zuraw, Kie. 2002. Vowel reduction in Palauan reduplicants. In Proceedings of AFLA 8, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 44, ed. Andrea Rackowski and Norvin Richards, 385–398.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the JEAL reviewers and Editors for their insightful comments and help, which have significantly improved the quality of the work presented here. This paper has benefited from the comments and questions by the audience at the 19th Old World Conference on Phonology in Verona, Italy. I would like to thank Rachel Walker and Yifang Yang for discussing relevant issues with me. Various parts of the paper were presented at the 1st International Symposium on Frontiers of Chinese Linguistics in Hong Kong and at a phonology workshop in the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, on December 3, 2019. Sincere thanks go to Lian-Hee Wee, San Duanmu, Carlos Gussenhoven, Paul Jen-kuei Li, Jackson Sun, Jonathan Evans, and the audiences for their valuable comments. All remaining errors are my own. This research is supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (MOST106-2410-H-001-039 and MOST107-2410-H-001-057-MY2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Hc.J. Glide strengthening in Atayal: sonority dispersion and similarity avoidance. J East Asian Linguist 29, 77–117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-020-09204-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-020-09204-w