Abstract

Background

The YOu and Ulcerative colitis: Registry and Social network (YOURS) is a large-scale, multicenter, patient-focused registry investigating the effects of lifestyle, psychological factors, and clinical practice patterns on patient-reported outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis in Japan. In this initial cross-sectional baseline analysis, we comprehensively explored impacts of symptom severity or proctocolectomy on nine patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

Patients receiving tertiary care at medical institutions were consecutively enrolled in the YOURS registry. The patients completed validated questionnaires on lifestyle, psychosocial factors, and disease-related symptoms. Severity of symptoms was classified with self-graded stool frequency and rectal bleeding scores (categories: remission, active disease [mild, moderate, severe]). The effects of symptom severity or proctocolectomy on nine scales for quality of life, fatigue, anxiety/depression, work productivity, and sleep were assessed by comparing standardized mean differences of the patient-reported outcome scores.

Results

Of the 1971 survey responses analyzed, 1346 (68.3%) patients were in remission, 583 (29.6%) had active disease, and 42 (2.1%) had undergone proctocolectomy. A linear relationship between increasing symptom severity and worsening quality of life, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and work productivity was observed. Patients with even mild symptoms had worse scores than patients in remission. Patients who had undergone proctocolectomy also had worse scores than patients in remission.

Conclusions

Ulcerative colitis was associated with reduced mood, quality of life, fatigue, and work productivity even in patients with mild symptoms, suggesting that management of active ulcerative colitis may improve patient-reported outcomes irrespective of disease severity. (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: UMIN000031995, https://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index-j.htm).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing and remitting inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the colon and rectum [1,2,3]. The majority of patients first present with symptoms of UC between their late 10 s and early 30 s [1]. The hallmark feature of active UC is bloody diarrhea, often accompanied by abdominal pain [1, 2]. To avoid unwanted clinical outcomes, including relapse, hospitalization, and colectomy, patients need to continue treatment throughout their lives with good communication and support from their healthcare providers (HCPs).

A major therapeutic target in IBD involves addressing and improving the patient’s overall burden of disease [4]. UC symptoms are distressing for patients, and the disease affects relationships, careers, and family life, with significant psychosocial impacts reported even in patients with ‘controlled’ symptoms [5, 6]. In a French study involving the administration of six validated questionnaires on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for patients with IBD, approximately half reported disease-induced depression and low quality of life (QOL) [7]. In another study, one-third of UC patients reported that they felt anxious and stigmatized [8]. Using the United States and European Union 5 data from the 2015 and 2017 Adelphi Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Specific Programme, a recent retrospective study in patients with moderate-to-severe UC demonstrated that active UC was significantly associated with reduced health-related QOL and leisure- and work-related impairment [9]. Thus, evaluating QOL, work productivity, fatigue, disability, anxiety, and depression by PROs is now recognized as an essential element in the management of IBD, and it is important for both patients and their HCPs to understand how the burden of disease may change with disease presentation [2, 7, 9].

Four key categories of modifiable factors to consider in improving patient outcomes have been identified: lifestyle (diet, physical activity, sleep, work); psychosocial factors (stress, depression, social support); practice patterns; and gaps between patients’ needs and HCPs’ practice [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The degree to which each of these factors influences outcomes in patients with UC is uncertain and the optimal lifestyle, psychosocial support, and practice patterns for this group of patients have been debated. The YOu and Ulcerative colitis: Registry and Social network (YOURS) is a large-scale, observational study investigating the effect of lifestyle, psychological factors, and clinical practice patterns on PROs and hospitalization and colectomy rates over 3 years in patients with UC in Japan [16]. The YOURS is a patient-focused registry that allows patients to access and compare their own data with summarized data from other patients. Patient-focused registries may improve healthcare by enabling patients, HCPs, and scientists to co-produce better health outcomes and support practice-based improvement [17]. Here, we report data focused on the impact of disease-related symptoms and proctocolectomy on PROs from the initial baseline survey for patients enrolled in the YOURS registry.

Methods

Study design

In this cross-sectional analysis, baseline data from the YOURS registry, a multicenter prospective, observational study, were analyzed [16]. A detailed description of the registry has been previously reported [16]. Briefly, the YOURS registry enrolled 2006 patients who have been diagnosed with UC according to the Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Inflammatory Bowel Disease [1]. Patients were enrolled during visits at five core IBD hospitals in Japan from May 2018 to January 2019. Enrolled patients were asked to complete surveys at the initial visit, 3 months after the initial visit (if in remission), and each year for up to 3 years after the initial visit. A three-item brief symptom survey was also conducted every 3 months after the initial visit. The protocol of this study has been posted to the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000031995).

Lifestyle, psychosocial factors, clinical practice patterns, and gaps between patient need and HCP practice were all assessed for their effects on PROs and unfavorable clinical outcomes, including relapse/exacerbation, hospitalization, and colectomy. Data collected at the initial visit were analyzed in this study.

Upon request, patients who participated in YOURS were given access to the registry website (https://ibd.pedal.or.jp/) where they could review their data over time, compare their data with other patients, and share their data with healthcare professionals, provided the patients have given written consent to transferring their data to the website.

Patient selection

Eligible patients had a diagnosis of UC, were aged ≥ 16 years at informed consent and were attending one of the five investigational sites. Consecutive enrolment commenced at each investigational site following approval by their respective ethics committee and continued until 2000 patients were enrolled in total across the sites or on 31 December 2018, whichever came later.

Survey items

At their initial visit, patients completed written questionnaire surveys with questions on demographic information, disease activity, disease characteristics (disease history, extraintestinal manifestations, abdominal pain, current and previous medication), socioeconomic status (employment, annual income, education, and social factors), lifestyle factors (physical activity, smoking history, sleep, and work), and PROs (Fig. 1).

YOURS Registry: Study Concept. *Collected from patient charts. FACIT-F Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, IPAQ International Physical Activity Questionnaire, JPSS Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale, mMOS-SS modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, PRO-2 Two-item Patient Reported Outcomes, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, QOL quality of life, SIBDQ Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, WPAI Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Remission was defined on the basis of the Two-Item Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO-2) questionnaire [18] as having a stool frequency score of 0 or 1 and a rectal bleeding score of 0 (total PRO-2 score of 0 or 1) [18, 19]. All patients not in remission were deemed as having active disease, and symptom severity was defined according to total PRO-2 score: 1 (excluding those in remission) or 2, mild; 3 or 4, moderate; and 5 or 6, severe.

As a disease characteristic, abdominal pain was measured by Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score [20], which ranges from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (worst pain ever possible). Social factors were assessed by the modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (mMOS-SS) [21, 22] and the Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale (JPSS) [23, 24]. Higher transformed mMOS-SS scores (range 0–100) reflected stronger social support. The sum of JPSS sub-scores (range 0–56) reflected more stress with higher scores. As a lifestyle factor, physical activity was measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [25, 26] and higher total Metabolic Equivalent Task (MET) score corresponds to higher physical activity (range 0–19,278). Physical activity was categorized as high, moderate, or low based on frequency, intensity, and length of activity and total MET [27]. Brinkman index was defined by the number of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years of smoking [28].

PROs were assessed by using the following instruments: Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) [29, 30], Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F) [31], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [32,33,34], Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) [35], and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [36, 37]. Ranges of SIBDQ sub-scores (divided by 10) for bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional function, and social function were 0.3–2.1, 0.2–1.4, 0.3–2.1, 0.2–1.4 (total score 1–7), respectively, with higher scores reflecting better IBD-related QOL. The FACIT-F score (range 0–52) of < 30 indicates severe fatigue [31, 38]. For the HADS scores for anxiety and depression (range 0–21 for each), the severity classes were defined as: normal, 0–7; mild, 8–10; moderate, 11–14; and severe, 15–21 [33]. WPAI outcomes were expressed as % of impairment, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less work productivity; the degree of impairment was defined as: mild 0–19%; moderate 20–49%; and severe ≥ 50% [35]. The PSQI contains 19 self-rated questions combined to form 7 component scores, each with a range of 0–3 (0, no difficulty; 3, severe difficulty) to yield a total PSQI score (range 0–21), with a higher score indicating lower sleep quality and a score > 5 indicating poor sleep quality [36].

Statistical analysis

Analysis groups were determined for each survey item and outcome measures. Descriptive statistics for demographic, lifestyle, and PRO data were computed for remission, active disease (mild, moderate, severe, and total), and post-proctocolectomy. Quantitative variables were summarized by the median (interquartile range [IQR]), and qualitative variables were expressed as the number (%). To compare the effect of symptom severity and proctocolectomy on the PROs, the standardized mean difference (SMD) [39] of the PROs and their 95% confidence intervals were computed using remission as the comparator, with the following formula:

The magnitude of the effect size was interpreted as: small, SMD = 0.2; medium, SMD = 0.5; and large, SMD = 0.8 [39]. In patients in remission and those with active disease, the variance of each PRO was modelled by linear regression and the fraction of variance explained by symptom severity was calculated. Correlations among pairs of PROs were assessed by calculating Spearman correlation coefficients in patients in remission and those with active disease who were assessable. For two-dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis, patients in remission and those with active disease who were assessable for all nine PROs were included. The PRO scores were standardized by subtracting the variable’s mean from each observed score, then dividing it by the variable’s standard deviation. For SIBDQ and FACIT-F, the sign of the standardized scores was flipped so that negative and positive values would correspond to better and worse symptoms, respectively. Euclidian distance between the variables was computed and clustered using the complete linkage algorithm.

The total number of analyzed patients and the number of missing cases were reported for each variable in the analysis. Imputation of missing data and data cleaning were carried out according to the instructions for each validated questionnaire. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 32-bit. Heatmaps and hierarchical clustering dendrograms were generated using heatmap.2 function from the gplots package (version 3.1.0) in R version 3.6.3.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and all applicable Japanese laws and guidelines. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the following five investigational sites (approval number) prior to study start: Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Medical Hospital (M2017-327-10); Kitasato University Kitasato Institute Hospital (18010); Kyorin University Hospital (1096); Tokyo Women's Medical University Hospital (4817); and Toho University Sakura Medical Center (S18043). All participants gave written informed consent before participating in this study. The study was registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000031995) before enrolment of the first patient.

Results

Patient demographics by disease activity and history of proctocolectomy

Of a total of 2731 UC patients attending the participating centers, 2006 (73.5%) patients were enrolled in the study. Of 1971 patients whose data were analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 1), 1346 (68.3%) patients were in remission, 583 (29.6%) had active disease, and 42 (2.1%) had undergone proctocolectomy. Patient demographics and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients who were in remission or had active disease was 44.0 years and 42.0 years, respectively, and 53–56% of these patients were male. Patients who had undergone proctocolectomy had a median age of 45.0 years, were 78.6% male, and 12 patients received ongoing treatment with immunomodulators (n = 2), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors (n = 6), systemic steroids (n = 5), tofacitinib (n = 1), and vedolizumab (n = 1).

Socioeconomic, educational, and social factors by disease activity and history of proctocolectomy

Socioeconomic and social factors are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1. Approximately 70% of patients in remission, those who had active disease, and those who had undergone proctocolectomy were in paid employment. Among patients with active disease, 22.4%, 20.0%, and 38.5% of those with mild, moderate, or severe symptoms, respectively, were unemployed. The proportion of patients with an annual income of JPY < 5 million (approximately USD 46,300) was 36.2% of patients in remission; 44.9% of patients with active disease, including 47.2%, 37.9%, and 65.4% of patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, respectively; and 52.3% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy.

Education profiles were similar across patient groups (remission, active disease, post-proctocolectomy); however, the proportion of patients whose highest level of educational attainment was high school or junior high school was disproportionally high in patients with severe symptoms.

Stress in patients with active disease increased with increasing symptom severity, with median values on the JPSS of 25, 26, and 29 for patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, respectively. Levels of social support were lowest for patients with severe symptoms and for those who had undergone proctocolectomy, with median mMOS-SS values of 68.75, compared with values of 75.00 for patients in remission and 71.88 for patients with mild or moderate symptoms (Supplementary Table 1). The proportion of patients living alone was 15.7% of patients in remission, 16.3% of patients with active disease (mild, moderate, or severe), and 28.6% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy. Among patients with active disease, 30.8% of patients with severe symptoms lived alone compared with 16.0% and 14.9% of patients with mild or moderate symptoms, respectively.

Lifestyle factors

Levels of physical activity, sleep and work in the remission, active disease, and post-proctocolectomy patient groups are shown in Table 2. On the basis of the IPAQ, the median total MET (minutes/week) of physical exercise was 1386 in the remission group, 1188 in patients with active disease, and 1164 in the post-proctocolectomy group. In terms of exposure to smoking, 61.3% of patients in remission, 61.4% of patients with active disease, and 45.2% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy had never smoked. Patients in the remission group slept for a median of 6.5 h per day, as did those in the post-proctocolectomy group. Patients who had active disease slept for a median of 6.0 h per day. The median number of work hours per week was 40.0 h for all patient groups.

Patient-reported outcomes

Median total SIBDQ scores were 5.9, 5.2, and 5.0 in patients in remission, patients with active disease, and those who had undergone proctocolectomy, respectively (Table 3). QOL was assessed as low in 17.1% of patients with a mild symptom score, 39.0% of those with a moderate symptom score, and 61.5% of those with a severe symptom score, versus 5.7% and 35.7% of patients in remission and those who had undergone proctocolectomy, respectively (Fig. 2a).

Proportion of patients reporting a QOL as low, normal or high on SIBDQ; b severe fatigue on FACIT-F; c depression or d anxiety on the HADS scale; e absenteeism, f presenteeism, g work productivity, and h activity impairment on WPAI; and i poor sleep quality on PSQI. FACIT-F Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, QOL quality of life, SIBDQ Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, WPAI Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Patients in remission had a median FACIT-F score of 44.0. In patients with active disease and those who had undergone proctocolectomy, median FACIT-F scores were 40.0 and 38.0, respectively (Table 3). The level of fatigue was assessed as severe in 6.6%, 13.8%, and 11.5% of patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptom scores, and 3.3% and 14.3% of patients in remission and those who had undergone proctocolectomy, respectively (Fig. 2b).

The median depression and anxiety sub-scores of HADS were 3.0 and 4.0, respectively, for patients in remission, versus 4.0 and 5.0, respectively, for patients with active disease, and 6.0 for both scores in patients who had undergone proctocolectomy (Table 3). HADS scores indicated that approximately 22% of patients with active disease and a mild symptom score had mild to moderate depression, and 24% had mild to moderate anxiety (Fig. 2c and d).

Responses to the WPAI questionnaire for patients in paid employment indicated severe absenteeism of 50% or more in 0.2% of patients in remission, 0%, 1.6%, and 13.3% of patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptom scores, respectively, and 7.7% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy (Fig. 2e). Severe presenteeism (≥ 50%) was reported by 8.2%, 29.7%, and 60.0% of patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptom scores, and 3.2% and 30.8% of patients in remission and those who had undergone proctocolectomy (Fig. 2f). Severe work productivity loss (≥ 50%) was reported by 3.4% of patients in remission, 9.1%, 29.7%, and 60.0% of patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptom scores, respectively, and 38.5% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy (Fig. 2g). In all patients irrespective of employment status, severe activity impairment of 50% or more was reported by 4.3% of patients in remission, 14.1%, 36.9%, and 65.4% of patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptom scores, respectively, and 42.9% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy (Fig. 2h). According to the PSQI, poor sleep quality was experienced by 54.8% of patients in remission, 62.7–70.8% of patients with active disease, and 73.8% of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy (Fig. 2i).

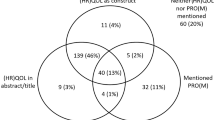

Multidimensional PROs and UC disease activity

Linear correlations were revealed between symptom severity and most PRO scores (Fig. 3). The magnitude of the impact of symptom severity varied widely among the nine PROs. Three WPAI sub-scores had the largest variance explained by symptom severity: activity impairment (23.0%), presenteeism (21.0%), and work productivity loss (20.2%) (Fig. 3). These three WPAI sub-scores showed strongest Spearman correlations (0.85–0.99) among one another (Table 4). Other PROs also showed strong positive correlations (FACIT-F and SIBDQ; and depression and anxiety) or negative correlations (WPAI impairment and SIBDQ; and depression and fatigue) (Table 4).

Associations of symptom severity and proctocolectomy with patient-reported outcomes. Data indicate SMD and their 95% confidence intervals. The fraction of variance of symptom severity explained by each outcome is shown in parentheses. The magnitude of the effect size was interpreted as: small, SMD = 0.2; medium, SMD = 0.5; and large, SMD = 0.8 [39]. Total number of patients included in the analysis were: SIBDQ (N = 1956), FACIT-F (N = 1935), HADS-D (N = 1958), HADS-A (N = 1958), WPAI-A (N = 1346), WPAI-P (N = 1346), WPAI-L (N = 1346), WPAI-I (N = 1909), and PSQI (N = 1917) (see Table 3 footnotes for breakdown by patient group). FACIT-F Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (A, anxiety; D, depression), PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, SIBDQ Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire, SMD standardized mean difference, WPAI Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (A, absenteeism; I, impairment of activity; L, loss of productivity; P, presenteeism)

In all nine measures, patients who had undergone proctocolectomy had scores closer to those obtained in patients in remission, but the scores did not completely revert (Fig. 3). Even a mild symptom score yielded a medium to large effect size (SMD ≥ 0.5) on SIBDQ and WPAI (activity impairment, presenteeism, and work productivity loss), whereas the effect size of PSQI and FACIT-F was small (SMD < 0.5) in patients with mild symptoms. Severe symptoms yielded an SMD of > 1.9 on WPAI subscales and 2.2 on SIBDQ (Fig. 3).

Hierarchical clustering analysis of PROs

To characterize the profiles of the PROs in patients in remission and those with active disease (mild, moderate, and severe), the nine PROs were clustered based on the Euclidian distances of their standardized scores using hierarchical clustering analysis. The four WPAI sub-scores clustered into one group (left side of the heatmap, Supplementary Fig. 2) and PSQI, HADS, FACIT-F, and SIBDQ into another (right side of the heatmap, Supplementary Fig. 2). Most patients with moderate or severe symptoms had worse PRO scores as did some patients with mild or no symptoms.

Discussion

The YOURS study is the first large-scale, prospective study assessing lifestyle and PROs in approximately 2000 patients with UC in Japan. In this initial baseline analysis, we found that UC is associated with reduced mood, QOL, fatigue, and work productivity even in patients with mild symptoms. The magnitude of the impact of UC on PROs increased with symptom severity and varied depending on the PRO assessed. PRO scores were favorable in patients in remission versus patients who had undergone proctocolectomy. UC symptom severity had the greatest magnitude of impact on WPAI among the PROs on a standardized scale, suggesting that decreased work productivity may represent a major challenge for working UC patients. Our results highlight the importance of monitoring work productivity in patients with UC to inform on treatment strategies to reduce the disease burden in patients.

Expectedly, QOL, as measured by the SIBDQ, was lower in patients with active disease than in those in remission. For patients in the active disease state, a worsening trend in QOL was observed for all measured SIBDQ domains, including bowel and systemic symptoms and emotional and social functioning, with increasing symptom severity. These findings echo the findings of recent research in the USA and Europe [9]. Our results showed that median SIBDQ scores were favorable in patients who had undergone proctocolectomy versus those with moderate-to-severe active disease, consistent with a recent meta-analysis showing that ileal pouch–anal anastomosis is associated with improved QOL [40]. This suggests that surgery remains an important intervention option for patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms and highlights the importance of surgical management in improving physical symptoms as well as QOL.

In line with previous studies in Austria, the USA, and Europe [9, 41], our data indicate that work productivity is substantially affected by UC, as reflected by the WPAI findings. In our study, the mean absenteeism increased as symptom severity increased (data not shown). Importantly, work productivity significantly decreased in patients with increasing symptom severity even though the work hours per week were similar across the patient groups. The loss of work productivity is inevitably associated with financial and societal costs. An important finding of our study is that even patients with mild symptom severity reported reductions in work productivity. Patients with severe symptoms, who reported the greatest loss in work productivity, were over-represented in the lower income or unemployed groups. Moreover, as symptom severity increased, social support decreased and stress and living alone increased. These results imply significant burden of the disease on the patient’s financial status and social life. Therefore, physicians must recognize the effect of UC symptoms on work productivity and its impact on their patients.

Our study also found that symptom severity correlates with mood. We found a linear relationship between increasing symptom severity and moderate decreases in HADS or FACIT-F scores. In a recent nationwide prospective cohort study conducted in Korea, significant mood disorders requiring psychological interventions (HADS score ≥ 11) were identified in 17–21% of patients with UC, but there was no significant difference in the mean HADS score according to symptom severity [42]. Villoria and colleagues found that fatigue was prevalent in quiescent IBD patients with moderate-to-severe disease [43]. Efficacy of current interventions for fatigue (including cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacological interventions) was inconclusive, highlighting the need for further research in this area [44].

PROs are of increasing importance given the shift to a more patient-centered approach towards IBD management. In fact, Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE)-II recommends the inclusion of PROs as an important treatment target in addition to clinical and endoscopic outcomes [45]. Our study serves to highlight current unmet needs in the management of UC across a varying disease severity spectrum. Over the past decade, many treatment options have emerged for the management of moderate-to-severe UC. However, our study finds that even in mild active disease, QOL and work productivity are substantially affected by UC. This highlights the need for improvement in the management of patients even at the mild end of the disease severity spectrum.

In our study, each PRO was assessed by multiple questions [16], which provides a deeper insight into the relationship between mild stages of UC and patient-reported QOL. Although the nine PRO assessment methods chosen in this study are all well established and/or validated [31, 46], the use of all these PRO tools may not be feasible in clinical practice. The IBD Disability Index was developed to measure disability in patients with IBD in daily practice [47]. The IBD Disk, a self-administered adaption of the IBD Disability Index, is an example of a valid and reliable tool for quantifying and monitoring IBD-related disability [4, 48]. The IBD Disk can be used to track changes in disease burden, and therefore it may be able to help in identifying patient-reported disability-related issues in the clinical setting [4].

The PRO scores of patients who had undergone proctocolectomy should be interpreted carefully. First, the sample size for patients who had undergone proctocolectomy was small (n = 42). Second, 12 (28.6%) of the 42 patients were receiving advanced therapies. This suggests that patients who had favorable surgery outcomes may be underrepresented in this study, possibly due to their less frequent hospital visits which may not have been captured during the 6-month enrolment period of this study. Despite these limitations, in all nine measures, patients who had undergone proctocolectomy had scores closer to those obtained in patients in remission than patients who had active disease. Whereas bowel symptoms or systemic symptom scores in SIBDQ were comparable in patients who had undergone proctocolectomy and patients in remission, emotional function and social function scores were lower in the patients who had undergone proctocolectomy. The reasons for these results should be explored in future studies.

The strengths of our study are (1) consecutive enrolment and large study size (more than 2000) and (2) usage of validated scales for all PROs. Conversely, the assessment of disease activity in our study lacked objective measures (endoscopy or fecal calprotectin). Although PRO-2 is reported to have significant correlation with UC disease activity based on endoscopic and histological features [49], it is solely based on patient self-reporting. Despite having a large patient cohort, patients were enrolled from a small number of investigation sites from the central region of Japan and thus may not represent the wider patient population in Japan. Patient numbers were also unequally distributed across symptom severity.

Further subgroup analyses on the correlation between PROs and symptom severity are required. Longitudinal evaluation of the relationships between disease status change and changes in PROs would be of value. Furthermore, evaluation of the relationships between PROs and types of therapeutic drug is of importance.

In summary, this study is the first large-scale prospective study assessing the challenges affecting PROs of patients with UC in Japan. The baseline data at the initial visit of this study demonstrated that many PROs were affected by UC symptom severity and proctocolectomy. There was a consistent trend of increasing impact on PROs with increasing symptom severity. The impact on PROs was found even in mild UC, suggesting that management of UC may improve PROs at all stages of disease severity.

Change history

30 May 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-024-02116-9

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FACIT-F:

-

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HCP:

-

Healthcare providers

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IPAQ:

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- JPSS:

-

Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale

- MET:

-

Metabolic Equivalent Task

- mMOS-SS:

-

Modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey

- NRS:

-

Numerical Rating Scale

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- PRO-2:

-

Two-item Patient Reported Outcomes

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- SIBDQ:

-

Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- STRIDE:

-

Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

- WPAI:

-

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

- YOURS:

-

YOu and Ulcerative colitis: Registry and Social network

References

Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:305–53.

Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:74.

da Silva BC, Lyra AC, Rocha R, et al. Epidemiology, demographic characteristics and prognostic predictors of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9458–67.

Ghosh S, Louis E, Beaugerie L, et al. Development of the IBD Disk: a visual self-administered tool for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333–40.

Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life—discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1281–6.

Calvet X, Argüelles-Arias F, López-Sanromán A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the impact of ulcerative colitis on social and professional life: results from the UC-LIFE survey of outpatient clinics in Spain. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1815–23.

Williet N, Sarter H, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in a French nationwide survey of inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:165–74.

Taft TH, Ballou S, Keefer L. A preliminary evaluation of internalized stigma and stigma resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Health Psychol. 2013;18:451–60.

Armuzzi A, Tarallo M, Lucas J, et al. The association between disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in the United States and Europe. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:18.

Jones PD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, et al. Exercise decreases risk of future active disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1063–71.

Parekh PJ, Oldfield Iv EC, Challapallisri V, et al. Sleep disorders and inflammatory disease activity: chicken or the egg? Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:484–8.

Tinsley A, Ehrlich OG, Hwang C, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding the role of nutrition in IBD among patients and providers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2474–81.

Barnes EL, Nestor M, Onyewadume L, et al. High dietary intake of specific fatty acids increases risk of flares in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission during treatment with aminosalicylates. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1390–6 (e1).

Kochar B, Barnes EL, Long MD, et al. Depression is associated with more aggressive inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:80–5.

Slonim-Nevo V, Sarid O, Friger M, et al. Effect of social support on psychological distress and disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1389–400.

Yamazaki H, Matsuoka K, Fernandez J, et al. Ulcerative colitis outcomes research in Japan: protocol for an observational prospective cohort study of YOURS (YOu and Ulcerative colitis: registry and social network). BMJ Open. 2019;9: e030134.

Nelson EC, Dixon-Woods M, Batalden PB, et al. Patient focused registries can improve health, care, and science. BMJ. 2016;354: i3319.

Jairath V, Khanna R, Zou GY, et al. Development of interim patient-reported outcome measures for the assessment of ulcerative colitis disease activity in clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1200–10.

Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, et al. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1660–6.

Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:798–804.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–14.

Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, et al. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:1107–16.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

Mimura C, Griffiths P. A Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale: translation and preliminary test. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41:379–85.

Murase N. Validity and reliability of Japanese version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire. J Health Welfare Stat. 2002;49:1–9.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95.

IPAQ Research Committee. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)-short and long forms. 2005. https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol. Accessed Sep 2022

Brinkman GL, Coates EO Jr. The effect of bronchitis, smoking, and occupation on ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1963;87:684–93.

Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571–8.

Casellas F, Alcala MJ, Prieto L, et al. Assessment of the influence of disease activity on the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease using a short questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:457–61.

Tinsley A, Macklin EA, Korzenik JR, et al. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1328–36.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Stern AF. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64:393–4.

Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Sarmiento-Aguilar A, García-Alanis M, et al. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): validation in Mexican patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:477–82.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–65.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213.

Doi Y, Minowa M, Uchiyama M, et al. Psychometric assessment of subjective sleep quality using the Japanese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-J) in psychiatric disordered and control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2000;97:165–72.

Saraiva S, Cortez-Pinto J, Barosa R, et al. Evaluation of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease - a useful tool in daily practice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:465–70.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Baker DM, Folan AM, Lee MJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after elective surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:18–33.

Walter E, Hausberger SC, Gross E, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity and costs related to patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Austria. J Med Econ. 2020;23:1061–71.

Moon JR, Lee CK, Hong SN, et al. Unmet psychosocial needs of patients with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis: results from the nationwide prospective cohort study in Korea. Gut Liver. 2020;14:459–67.

Villoria A, Garcia V, Dosal A, et al. Fatigue in out-patients with inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and predictive factors. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181435.

Farrell D, Artom M, Czuber-Dochan W, et al. Interventions for fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4: CD012005.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–38.

Han SW, Gregory W, Nylander D, et al. The SIBDQ: further validation in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:145–51.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, et al. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut. 2012;61:241–7.

Le Berre C, Flamant M, Bouguen G, et al. VALIDation of the IBD-disk instrument for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases in a French cohort: the VALIDate study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1512–23.

Dragasevic S, Sokic-Milutinovic A, Stojkovic Lalosevic M, et al. Correlation of patient-reported outcome (PRO-2) with endoscopic and histological features in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:2065383.

Acknowledgements

We thank Philippe Pinton from JMO Takeda for review of initial draft of the manuscript. Statistical analysis was provided by Sven Demiya, Masafumi Okada, and Chihiro Foellscher of IQVIA, sponsored by Takeda. We thank the patients and healthcare professionals involved in this study. We are grateful to the Japanese Society for Inflammatory Bowel Disease for their input in the study design. Medical writing assistance was provided by Milly Farrand and Fumiko Shimizu on behalf of MIMS, sponsored by Takeda, in compliance with the Good Publication Practice guidelines (updated on 30 August 2022; https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Funding

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited funded this study, assisted with designing the study, and supported data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM, HY, TK, JF, SF, and TaH contributed to the conception and design of the study. KM, MN, TK, TO, and TaH contributed to the acquisition of data. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation, as well as revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval for the manuscript to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Katsuyoshi Matsuoka has received honoraria and research grants from AbbVie, EA Pharma, Pfizer, Mochida, Kyorin, ZERIA, Kissei, Nippon Kayaku, JIMRO, and honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe, Takeda, Janssen, MIYARISAN and Celltrion Healthcare. Hajime Yamazaki has received an honorarium from Takeda. Masakazu Nagahori has received honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe, Janssen, Kyorin, AbbVie, and research grants from Takeda, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. Taku Kobayashi has received honoraria and research grants from Takeda, Activaid, Alfresa, ZERIA, Kyorin, Nippon Kayaku, Mitsubishi Tanabe, AbbVie, Pfizer, Janssen, JIMRO, EA Pharma, Mochida, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, honoraria from Thermo Fisher diagnostics, Galapagos, Kissei, and research grants from JMDC, Gilead Sciences, Otsuka and Google Asia Pacific. Teppei Omori has received an honorarium from Takeda. Toshimitsu Fujii has received honoraria and research grants from AbbVie, EA Pharma, Janssen, Kissei, Nichiiko, Takeda, ZERIA, honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mochida, Nippon Kayaku, and research grants from Alfresa, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Gilead Sciences. Shinichiro Shinzaki has received honoraria from AbbVie, Alfresa, AstraZeneca, EA Pharma, Eisai, Gilead Sciences, Kissei, Kyorin, Janssen, JIMRO, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mochida, Nippon Kayaku, Pfizer, Sekisui Medical, Takeda, ZERIA, and a research grant from Sekisui Medical. Masayuki Saruta has received honoraria and scholarship grants from AbbVie, EA Pharma, ZERIA, Kissei, Mochida, and honoraria from Janssen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences and Takeda. Minoru Matsuura has received honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Kyorin, Mochida, Viatris, Nippon Kayaku, EA Pharma, JIMRO, ZERIA and Aspen. Toshifumi Hibi has received honoraria and research grants from AbbVie, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mochida, Takeda, ZERIA, Kyorin, JIMRO, honoraria from Sandoz, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, EA Pharma, APO PLUS STATION, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Nichi-Iko, and research grants from Otsuka, Alfresa and MIYARISAN. Mamoru Watanabe has received honoraria and research grants from EA Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Takeda, ZERIA, Kissei, Mochida, AbbVie, honoraria from Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Celltrion Healthcare, JIMRO, Eli Lilly, and research grants from Nippon Kayaku, Kyorin and Alfresa. Jovelle Fernandez was an employee of Takeda when the study was conducted and owns restricted stocks of Takeda and GlaxoSmithKline. Shunichi Fukuhara has received an honorarium from Takeda. Tadakazu Hisamatsu has received honoraria from EA Pharma, AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer, Nichi-Iko, Mitsubishi Tanabe, AbbVie, Kyorin, JIMRO, Mochida, Takeda, research grants from Alfresa and EA Pharma, and scholarship grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe, EA Pharma, AbbVie, JIMRO, ZERIA, Daiichi Sankyo, Kyorin, Nippon Kayaku, Takeda, Pfizer and Mochida. Yohei Mikami, Takayuki Yamamoto, and Satoshi Motoya declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuoka, K., Yamazaki, H., Nagahori, M. et al. Association of ulcerative colitis symptom severity and proctocolectomy with multidimensional patient-reported outcomes: a cross-sectional study. J Gastroenterol 58, 751–765 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-023-02005-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-023-02005-7