Abstract

Over a decade has passed since the first human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was introduced. These vaccines have received unequivocal backing from the scientific and medical communities, yet continue to be debated in the media and within the general public. The current review is an updated examination that the authors made five years ago on some of the key sociocultural and behavioral issues associated with HPV vaccine uptake and acceptability, given the changing HPV vaccine policies and beliefs worldwide. We explore current worldwide HPV vaccination rates, outline HPV vaccine policies, and revisit critical issues associated with HPV vaccine uptake including: risk compensation, perceptions of vaccine safety and efficacy, age of vaccination, and healthcare provider (HCP) recommendation and communication. While public scrutiny of the vaccine has not subsided, empirical evidence supporting its safety and efficacy beyond preventing cervical cancer has amassed. There are conclusive findings showing no link that vaccinated individuals engage in riskier sexual behaviors as a result of being immunized (risk compensation) both at the individual and at the policy level. Finally, HCP recommendation continues to be a central factor in HPV vaccine uptake. Studies have illuminated how HCP practices and communication enhance uptake and alleviate misperceptions about HPV vaccination. Strategies such as bundling vaccinations, allowing nurses to vaccinate via “standing orders,” and diversifying vaccination settings (e.g., pharmacies) may be effective steps to increase rates. The successes of HPV vaccination outweigh the controversy, but as the incidence of HPV-related cancers rises, it is imperative that future research on HPV vaccine acceptability continues to identify effective and targeted strategies to inform HPV vaccination programs and improve HPV coverage rates worldwide.

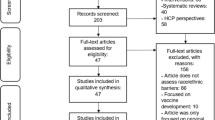

(From Cervical Cancer Action. Global maps: global progress in HPV vaccination. 2017. Available at: http://www.cervicalcanceraction.org/comments/comments3.php. Accessed 24 Aug 2017)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

HPV up-to-date rates were defined as those with three or more doses, and those with two doses when the first HPV vaccine dose was initiated before age 15 years and the time between the first and second dose was at least 5 months minus 4 days.

References

Zimet GD, Rosberger Z, Fisher WA, Perez S, Stupiansky NW. Beliefs, behaviors and HPV vaccine: correcting the myths and the misinformation. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):414–8.

Brotherton JML, Zuber PLF, Bloem PJN. Primary prevention of HPV through vaccination: update on the current global status. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2016;5(3):210–24.

Daley EM, Vamos CA, Thompson EL, Zimet GD, Rosberger Z, Merrell L, et al. The feminization of HPV: how science, politics, economics and gender norms shaped US HPV vaccine implementation. Papillomavirus Res. 2017;3:142–8.

Petrosky E, Bocchini JJ, Hariri S, Chesson H, Curtis CR, Saraiya M, et al. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(11):300–4.

Wigle J, Fontenot HB, Zimet GD. Global delivery of human papillomavirus vaccines. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2016;63(1):81–95.

Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, et al. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(7):e453–63.

Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Munoz N, Block SL, Brown DR, DiNubile MJ, et al. Impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review of ten years of real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):519–27.

Drolet M, Bénard É, Boily M-C, Ali H, Baandrup L, Bauer H, et al. Population-level impact and herd effects following human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):565–80.

Kjaer SK, Nygård M, Dillner J, Brooke Marshall J, Radley D, Li M, et al. A 12-year follow-up on the long-term effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in 4 Nordic countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):339–45.

Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O-E, Bouchard C, Mao C, Mehlsen J, et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–23.

Luostarinen T, Apter D, Dillner J, Eriksson T, Harjula K, Natunen K, et al. Vaccination protects against invasive HPV-associated cancers. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(10):2186–7.

Costa APF, Cobucci RNO, da Silva JM, da Costa Lima PH, Giraldo PC, Goncalves AK. Safety of human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:3736201.

Gee J, Weinbaum C, Sukumaran L, Markowitz LE. Quadrivalent HPV vaccine safety review and safety monitoring plans for nine-valent HPV vaccine in the United States. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12(6):1406–17.

Van Damme P, Olsson SE, Block S, Castellsague X, Gray GE, Herrera T, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 9-valent HPV vaccine. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e28–39.

Larson HJ. Japanese media and the HPV vaccine saga. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(4):533–4.

Tsuda K, Yamamoto K, Leppold C, Tanimoto T, Kusumi E, Komatsu T, et al. Trends of media coverage on human papillomavirus vaccination in Japanese newspapers. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(12):1634–8.

Tanaka Y, Ueda Y, Egawa-Takata T, Yagi A, Yoshino K, Kimura T. Outcomes for girls without HPV vaccination in Japan. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):868–9.

Power J. HPV vaccine uptake rate falls 15% among young girls. Irish Times. 2017;3:2017.

Dawar M, Dobson S, Deeks S. Literature review on HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18: disease and vaccine characteristics. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC); 2007. p. 1–33. Retrieved from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/naci-ccni/pdf/lr-sl_2_e.pdf.

Mariani L, Vici P, Suligoi B, Checcucci-Lisi G, Drury R. Early direct and indirect impact of quadrivalent HPV (4HPV) vaccine on genital warts: a systematic review. Adv Ther. 2015;32(1):10–30.

Cuzick J. Gardasil 9 joins the fight against cervix cancer. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(8):1047–9.

Cervical Cancer Action. Global progress in HPV vaccine introduction. 2017. Retrieved from: http://www.cervicalcanceraction.org/comments/comments3.php.

LaMontagne DS, Bloem PJ, Brotherton JM, Gallagher KE, Badiane O, Ndiaye C. Progress in HPV vaccination in low-and lower-middle-income countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2017;138(S1):7–14.

Gallagher KE, Howard N, Kabakama S, Mounier-Jack S, Griffiths UK, Feletto M, et al. Lessons learnt from human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in 45 low-and middle-income countries. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0177773.

Owsianka B, Gańczak M. Evaluation of human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination strategies and vaccination coverage in adolescent girls worldwide. Prz Epidemiol. 2015;69(1):53–8.

Machalek DA, Garland SM, Brotherton JML, Bateson D, McNamee K, Stewart M, et al. Very low prevalence of vaccine human papillomavirus types among 18- to 35-year old australian women 9 years following implementation of vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:1590–600.

Chow EP, Danielewski JA, Fehler G, Tabrizi SN, Law MG, Bradshaw CS, et al. Human papillomavirus in young women with Chlamydia trachomatis infection 7 years after the Australian human papillomavirus vaccination programme: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(11):1314–23.

Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, Read TR, Regan DG, Grulich AE, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2013;18(346):f2032.

Lee LY, Garland SM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: the population impact. F1000Research. 2017;6(F1000 Faculty Rev):866. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10691.1.

Hull BP, Hendry AJ, Dey A, Beard FH, Brotherton JM, McIntyre PB. Immunisation coverage annual report, 2014. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2017;41(1):E68–90.

Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years—United States, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):909–917.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canada’s provincial and territorial routine (and catch-up) vaccination programs for infants and children. 2017 December 2017 [cited]. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information/childhood_schedule-12-2017.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2018.

El Emam K, Samet S, Hu J, Peyton L, Earle C, Jayaraman GC, et al. A protocol for the secure linking of registries for HPV surveillance. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(7):e39915.

Busby C, Chesterley N. A Shot in the Arm: How to Improve Vaccination Policy in Canada (March 12, 2015). C.D. Howe Institute Commentary, No. 421. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2578035 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2578035. Accessed 21 Mar 2018.

Bird Y, Obidiya O, Mahmood R, Nwankwo C, Moraros J. Human papillomavirus vaccination uptake in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:71.

Shapiro GK, Guichon J, Kelaher M. Canadian school-based HPV vaccine programs and policy considerations. Vaccine. 2017;35(42):5700–7.

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Immunization coverage report for school pupils: 2013–14, 2014–15 and 2015–16 school year. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2017.

McClure CA, MacSwain MA, Morrison H, Sanford CJ. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in boys and girls in a school-based vaccine delivery program in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Vaccine. 2015;33(15):1786–90.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Vaccine schedule. 2019 [cited]. https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu. Accessed 19 July 2018.

Kalinowski P, Grzadziel A. HPV vaccinations in Lublin Region, Poland. Postepy higieny i medycyny doswiadczalnej (Online). 2017;71:92–7.

Latsuzbaia A, Arbyn M, Weyers S, Mossong J. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage in Luxembourg - Implications of lowering and restricting target age groups. Vaccine. 2018;36(18):2411–6.

Restivo V, Costantino C, Fazio T, Casuccio N, D’Angelo C, Vitale F, et al. Factors associated with HPV vaccine refusal among young adult women after ten years of vaccine implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):770.

Top G. The HPV vaccination programme in Flanders. In: Building trust, managing risk: vaccine confidence and human papillomavirus vaccination, London, England; 2017. Retrieved from https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/projects/hpv-prevention-control-board/meetings-/building-trust--mana/. Accessed 21 Mar 2018.

HPV Prevention and Control Board. Meeting Report. Paper presented at the Building trust, managing risks: vaccine confidence and human papillomavirus vaccination, London, England. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.uantwerpen.be/images/online/hpv/meeting-report-london/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#1.

Klinsupa W, Pensuk P, Thongluan J, Boonsut S, Tragoolpua R, Yoocharoen P, et al. HPV vaccine introduction in Thailand. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91(Suppl 2):A61.

Yin Y. HPV vaccination in China needs to be more cost-effective. Lancet. 2017;390(10104):1735–6.

Heffelfinger J (2018) HPV Vaccination in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia Regions: Overview, Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: https://www.sabin.org/sites/sabin.org/files/james_heffelfinger.pdf.

Fisher WA, Laniado H, Shoval H, Hakim M, Bornstein J. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability in Israel. Vaccine. 2013;31:I53–7.

Velan B, Yadgar Y. On the implications of desexualizing vaccines against sexually transmitted diseases: health policy challenges in a multicultural society. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017;6(1):30.

RIVM (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment). Vaccination rate again drops slightly, HPV vaccination rate drops considerably. Netherlands; 2018. Retrieved from https://www.rivm.nl/en/Documents_and_publications/Common_and_Present/Newsmessages/2018/Vaccination_rate_again_drops_slightly_HPV_vaccination_rate_drops_considerably. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

World Health Organization. Denmark campaign rebuilds confidence in HPV vaccination. Features 2018 [cited]. Retrieve from http://www.who.int/features/2018/hpv-vaccination-denmark/en/. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Corcoran B, Clarke A, Barrett T. Rapid response to HPV vaccination crisis in Ireland. Lancet. 2018;391(10135):2103.

Hanley SJ, Yoshioka E, Ito Y, Kishi R. HPV vaccination crisis in Japan. Lancet. 2015;385(9987):2571.

Saldaña A, Avendaño M. Vaccination campaign against human papilloma virus in Chile. In: Building trust, managing risk: vaccine confidence and human papillomavirus vaccination, London, England; 2017. Retrieved from https://www.uantwerpen.be/images/uantwerpen/container39248/files/2017%2006%20London/06_%20Jan%20Wilhelm.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2018.

Agosti JM, Goldie SJ. Introducing HPV vaccine in developing countries—key challenges and issues. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1908–10.

Casper MJ, Carpenter LM. Sex, drugs, and politics: the HPV vaccine for cervical cancer. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30(6):886–99.

Haber G, Malow RM, Zimet GD. The HPV vaccine mandate controversy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20(6):325–31.

Markowitz LE, Tsu V, Deeks SL, Cubie H, Wang SA, Vicari AS, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction—the first five years. Vaccine. 2012;30:F139–48.

Colgrove J, Abiola S, Mello MM. HPV vaccination mandates—lawmaking amid political and scientific controversy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):785–91.

Guichon J, Mitchell I, Buffler P, Caplan A. Citizen intervention in a religious ban on in-school HPV vaccine administration in Calgary, Canada. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):409–13.

Malagón T, Franco E. Human papillomavirus vaccination: making sense of the public controversy. In: Campisi P, editor. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Cham: Springer; 2018.

Stein R. Cervical cancer vaccine gets injected with a social issue. Washington Post; 2005. Retrieved from: https://pol285.blog.gustavus.edu/files/2009/08/WP_HPV_Vaccine_Politics.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2018.

Gibbs N. Defusing the war over the “promiscuity” vaccine. Time; 2006. Available at: http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1206813,00.html. Accessed 21 Feb 2018.

Forster AS, Marlow LAV, Stephenson J, Wardle J, Waller J. Human papillomavirus vaccination and sexual behaviour: cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys conducted in England. Vaccine. 2012;30(33):4939–44.

Waller J, Marlow LAV, Wardle J. Mothers’ attitudes towards preventing cervical cancer through human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:1257–61.

Kasting ML, Shapiro GK, Rosberger Z, Kahn JA, Zimet GD. Tempest in a teapot: a systematic review of HPV vaccination and risk compensation research. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12(6):1435–50.

Madhivanan P, Pierre-Victor D, Mukherjee S, Bhoite P, Powell B, Jean-Baptiste N, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination and sexual disinhibition in females: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(3):373–83.

Zimmermann M, Kohut T, Fisher WA. HPV unvaccinated status and HPV sexual risk behaviour are common among canadian young adult women and men. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40(4):410–7.

Stern AM, Markel H. The history of vaccines and immunization: familiar patterns, new challenges. Health Aff. 2005;24(3):611–21.

Young A. HPV vaccine acceptance among women in the Asian Pacific: a systematic review of the literature. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(3):641–9.

Garcini LM, Galvan T, Barnack-Tavlaris JL. The study of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake from a parental perspective: a systematic review of observational studies in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(31):4588–95.

Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3546–56.

Chan ZC, Chan TS, Ng KK, Wong ML. A systematic review of literature about women’s knowledge and attitudes toward human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Public Health Nurs. 2012;29(6):481–9.

Hendry M, Lewis R, Clements A, Damery S, Wilkinson C. “HPV? Never heard of it!”: a systematic review of girls’ and parents’ information needs, views and preferences about human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31(45):5152–67.

Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):700–22.

Prue G, Shapiro G, Maybin R, Santin O, Lawler M. Knowledge and acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination in adolescent boys worldwide: a systematic review. J Cancer Policy. 2016;10:1–15.

Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(2–3):107–14.

Klug SJ, Hukelmann M, Blettner M. Knowledge about infection with human papillomavirus: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008;46(2):87–98.

Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards human papillomavirus vaccination for their children: a systematic review from 2001 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:1–12.

Cunningham MS, Davison C, Aronson KJ. HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2014;69:274–9.

Newman PA, Logie CH, Doukas N, Asakura K. HPV vaccine acceptability among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(7):568–74.

Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82.

Nadarzynski T, Smith H, Richardson D, Jones CJ, Llewellyn CD. Human papillomavirus and vaccine-related perceptions among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(7):515–23.

Patel H, Jeve YB, Sherman SM, Moss EL. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and the human papillomavirus vaccine in European adolescents: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(6):474–9.

Radisic G, Chapman J, Flight I, Wilson C. Factors associated with parents’ attitudes to the HPV vaccination of their adolescent sons: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2017;95:26–37.

Santhanes D, Wong CP, Yap YY, San SP, Chaiyakunapruk N, Khan TM. Factors involved in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine hesitancy among women in the South-East Asian Region (SEAR) and Western Pacific Region (WPR): a scoping review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(1):124–33.

Fisher WA. Understanding human papillomavirus vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2012;30:F149–56.

Francis DB, Cates JR, Wagner KPG, Zola T, Fitter JE, Coyne-Beasley T. Communication technologies to improve HPV vaccination initiation and completion: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:1280–6.

Fu LY, Bonhomme LA, Cooper SC, Joseph JG, Zimet GD. Educational interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptance: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32(17):1901–20.

Walling EB, Benzoni N, Dornfeld J, Bhandari R, Sisk BA, Garbutt J, et al. Interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20153863.

Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: a systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12(6):1566–88.

Niccolai LM, Hansen CE. Practice- and community-based interventions to increase human papillomavirus vaccine coverage: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):686–92.

Kang HS, De Gagne JC, Son YD, Chae S-M. Completeness of human papilloma virus vaccination: a systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;39:7–14.

Jemal A, Bray F, Center M, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? 2017 March 3, 2017 [cited]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Accessed July 2018.

Udager AM, McHugh JB. Human papillomavirus-associated neoplasms of the head and neck. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10(1):35–55.

Herrero R, Quint W, Hildesheim A, Gonzalez P, Struijk L, Katki HA, et al. Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PloS One. 2013;8(7):e68329.

Hirth JM, Chang M, Resto VA, Guo F, Berenson AB. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus by vaccination status among young adults (18–30 years old). Vaccine. 2017;35(27):3446–51.

Pinto LA, Kemp TJ, Torres BN, Isaacs-Soriano K, Ingles D, Abrahamsen M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine induces HPV-specific antibodies in the oral cavity: results from the Mid-Adult Male Vaccine Trial. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(8):1276–83.

Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, Pickard RKL, Tong Z-Y, Xiao W, et al. Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on oral HPV infections among young adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(3):262–7.

Frisch M, Smith E, Grulich A, Johansen C. Cancer in a population-based cohort of men and women in registered homosexual partnerships. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(11):966–72.

Goldstone S, Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Moreira ED Jr, Aranda C, Jessen H, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among HIV-seronegative men who have sex with men. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(1):66–74.

Forster A, Wardle J, Stephenson J, Waller J. Passport to promiscuity or lifesaver: press coverage of HPV vaccination and risky sexual behavior. J Health Commun. 2010;15(2):205–17.

Kahn JA, Lee J, Belzer M, Palefsky JM, Consortium AM. Interventions AMTNfHA. HIV-infected young men demonstrate appropriate risk perceptions and beliefs about safer sexual behaviors after human papillomavirus vaccination. AIDS Behav. 2017;22(6):1–9.

Mullins TLK, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, Ding L, Morrow C, Huang B, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine-related risk perceptions do not predict sexual initiation among young women over 30 months following vaccination. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(2):164–9.

Vázquez-Otero C, Thompson EL, Daley EM, Griner SB, Logan R, Vamos CA. Dispelling the myth: exploring associations between the HPV vaccine and inconsistent condom use among college students. Prev Med. 2016;93:147–50.

Cook EE, Venkataramani AS, Kim JJ, Tamimi RM, Holmes MD. Legislation to increase uptake of HPV vaccination and adolescent sexual behaviors. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20180458.

Schuler CL, Reiter PL, Smith JS, Brewer NT. Human papillomavirus vaccine and behavioural disinhibition. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(4):349–53.

Marlow LAV, Forster AS, Wardle J, Waller J. Mothers’ and adolescents’ beliefs about risk compensation following HPV vaccination. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(5):446–51.

Brabin L, Roberts SA, Stretch R, Baxter D, Chambers G, Kitchener H, et al. Uptake of first two doses of human papillomavirus vaccine by adolescent schoolgirls in Manchester: prospective cohort study. Br Med J. 2008;336(7652):1056–8.

Mayer MK, Reiter PL, Zucker RA, Brewer NT. Parents’ and sons’ beliefs in sexual disinhibition after human papillomavirus vaccination. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(10):822.

Beavis A, Krakow M, Levinson K, Rositch A. Reasons for persistent suboptimal rates of HPV vaccination in the US: shifting the focus from sexuality to education and awareness. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:4.

Perez S, Tatar O, Shapiro GK, Dubé E, Ogilvie G, Guichon J, et al. Psychosocial determinants of parental human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine decision-making for sons: methodological challenges and initial results of a pan-Canadian longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1223.

Shapiro GK, Perez S, Naz A, Tatar O, Guichon JR, Amsel R, et al. Investigating Canadian parents’ HPV vaccine knowledge, attitudes and behaviour: a study protocol for a longitudinal national online survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017814.

Public Health Agency of Canada. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS). National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Update on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. Internet; 2012. Report No. ASC-1. ISSN:1481-8531.

Public Health Agency of Canada. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Update on the recommended human papillomavirus vaccine immunization schedule. Internet; 2015. Report No. ISBN:978-1-100-25456-2. Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/aspc-phac/HP40-128-2014-eng.pdf.

Macartney KK, Chiu C, Georgousakis M, Brotherton JML. Safety of human papillomavirus vaccines: a review. Drug Saf. 2013;36(6):393–412.

Vichnin M, Bonanni P, Klein NP, Garland SM, Block SL, Kjaer SK, et al. An overview of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine safety: 2006 to 2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(9):983–91.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine safety monitoring. 2016. June 7 2016 [cited]. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/index.html. Accessed July 2018.

Immunize Canada. Safety. 2016 [cited 2017 May 31]. http://www.immunize.ca/en/vaccine-safety.aspx. Accessed Feb 2018.

English K. Public editor criticizes the Star’s Gardasil story. Toronto Star; 2015.

Health Protection Surveillance Centre. 2018 [cited]. Retrieved from: http://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/vaccinepreventable/vaccination/immunisationuptakestatistics/hpvimmunisationuptakestatistics/HPV%20Uptake%20Academic%20Year%202016%202017%20v1.1%2009012018.pdf. Uptake Academic Year 2016 2017 v1.1 09012018.pdf. Accessed July 2018.

Soares LC, Brollo JLA. Response to: Survey of Japanese mothers of daughters eligible for human papillomavirus vaccination on attitudes about media reports of adverse events and the suspension of governmental recommendation for vaccination. J Obstetr Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(5):593–4.

Sample I. Doctor wins 2017 John Maddox prize for countering HPV vaccine misinformation. The Guardain. 30 November 2017; 2017.

Guichon J, Kaul R. Science shows HPV vaccine has no dark side. Toronto Star. 2015;11:2015.

Paul KT. “Saving lives”: adapting and adopting human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination in Austria. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:193–200.

Bendik M, Mayo RM, Parker VG. Contributing factors to HPV vaccine uptake in college-age women. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24(1):17.

Perez S, Tatar O, Gilca V, Shapiro GK, Ogilvie G, Guichon J, et al. Untangling the psychosocial predictors of HPV vaccination decision-making among parents of boys. Vaccine. 2017;35(36):4713–21.

Tatar O, Perez S, Naz A, Shapiro GK, Rosberger Z. Psychosocial correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability in college males: a cross-sectional exploratory study. Papillomavirus Res. 2017;4:99–107.

Stokley S, Jeyarajah J, Yankey D, Cano M, Gee J, Roark J, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2014—United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):620–4.

Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(11):1673–9.

Shay LA, Street RL, Baldwin AS, Marks EG, Lee SC, Higashi RT, et al. Characterizing safety-net providers’ HPV vaccine recommendations to undecided parents: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(9):1452–60.

Sturm L, Donahue K, Kasting M, Kulkarni A, Brewer NT, Zimet GD. Pediatrician-parent conversations about human papillomavirus vaccination: an analysis of audio recordings. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(2):246–51.

Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161764.

Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34:1187–92.

Krantz L, Ollberding NJ, Beck AF, Carol Burkhardt M. Increasing HPV vaccination coverage through provider-based interventions. Clin Pediatr. 2017;57:319–26.

Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, Heritage J, DeVere V, Salas HS, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):1998–2004.

Dexter PR, Perkins SM, Maharry KS, Jones K, McDonald CJ. Inpatient computer-based standing orders vs physician reminders to increase influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2366–71.

Calo WA, Gilkey MB, Shah P, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Parents’ willingness to get human papillomavirus vaccination for their adolescent children at a pharmacy. Prev Med. 2017;99:251–6.

Briones R, Nan X, Madden K, Waks L. When vaccines go viral: an analysis of HPV vaccine coverage on YouTube. Health Commun. 2012;27(5):478–85.

Dyer O. Canadian academic’s call for moratorium on HPV vaccine sparks controversy. BMJ 2015;351:h5692. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5692.

Kata A. A postmodern Pandora’s box: anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine. 2010;28(7):1709–16.

HPV Awareness.org. Quebec children deserve the same cancer protection as the rest of Canada. Retrieved from: https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/quebec-children-deserve-the-same-cancer-protection-as-the-rest-of-canada---why-change-an-hpv-vaccination-program-that-has-stood-the-test-of-time-693627001.html.

Kreimer AR, National Cancer Institute. Scientific evaluation of one or two doses of the bivalent or nonavalent prophylactic hpv vaccines. Costa Rica: National Cancer Institute (NCI) Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03180034.

Dilley SE, Peral S, Straughn JM Jr, Scarinci IC. The challenge of HPV vaccination uptake and opportunities for solutions: lessons learned from Alabama. Prev Med. 2018;113:124–31.

Spencer JC, Brewer NT, Trogdon JG, Wheeler SB, Dusetzina SB. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine follow-through among privately insured US patients. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(7):946–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Authors SP, OT, NS, and ZR have no conflicts of interest to declare. Author WF has served as a speaker concerning HPV vaccination for Merck Canada. GZ has received an honorarium from Sanofi Pasteur for participation in an adolescent immunization initiative meeting.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perez, S., Zimet, G.D., Tatar, O. et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: Successes and Future Challenges. Drugs 78, 1385–1396 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0975-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0975-6