Abstract

This trial assessed the feasibility and acceptability of Kidney BEAM, a physical activity and emotional well-being self-management digital health intervention (DHI) for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which offers live and on-demand physical activity sessions, educational blogs and videos, and peer support. In this mixed-methods, multicentre randomised waitlist-controlled internal pilot, adults with established CKD were recruited from five NHS hospitals and randomised 1:1 to Kidney BEAM or waitlist control. Feasibility outcomes were based upon a priori progression criteria. Acceptability was primarily explored via individual semi-structured interviews (n = 15). Of 763 individuals screened, n = 519 (68%, 95% CI 65 to 71%) were eligible. Of those eligible, n = 303 (58%, 95% CI 54–63%) did not respond to an invitation to participate by the end of the pilot period. Of the 216 responders, 50 (23%, 95% CI 18–29%) consented. Of the 42 randomised, n = 22 (10 (45%) male; 49 ± 16 years; 14 (64%) White British) were allocated to Kidney BEAM and n = 20 (12 (55%) male; 56 ± 11 years; 15 (68%) White British) to the waitlist control group. Overall, n = 15 (30%, 95% CI 18–45%) withdrew during the pilot phase. Participants completed a median of 14 (IQR 5–21) sessions. At baseline, 90–100% of outcome data (patient reported outcome measures and a remotely conducted physical function test) were completed and 62–83% completed at 12 weeks follow-up. Interview data revealed that remote trial procedures were acceptable. Participants’ reported that Kidney BEAM increased their opportunity and motivation to be physically active, however, lack of time remained an ongoing barrier to engagement with the DHI. An randomised controlled trial of Kidney BEAM is feasible and acceptable, with adaptations to increase recruitment, retention and engagement.

Trial registration NCT04872933. Date of first registration 05/05/2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects over 800 million adults worldwide and is associated with lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL)1,2. Physical activity and emotional- wellbeing self-management support have a beneficial impact on HRQoL in this population3, and are key elements in the management of many long-term conditions4. Despite this, there is limited access to this type of care for people with CKD4,5.

Digital health interventions (DHIs) may offer a clinically and cost-effective means of addressing barriers to accessing support for physical activity and emotional well-being6,7,8. Digital health interventions can significantly improve clinical outcomes in people with CKD, but existing DHIs do not specifically focused upon physical activity and emotional well-being4,9. There is an urgent need for high-quality, large-scale trials focussing upon patient-centred outcomes9. In addition, reviews of barriers and facilitators to physical activity DHIs suggest that they need to be tailored to the requirements of the specific long-term condition10, yet here is little research into the specific views of people with CKD concerning DHIs9,11. Understanding these perspectives and beliefs is crucial to ensuring that DHIs meet the needs of a diverse range of people9.

Aims

Kidney BEAM is a DHI which has been co-developed with people with CKD to support physical activity and emotional well-being self-management. A multicentre prospective, wait-list randomised controlled trial (RCT) will evaluate whether Kidney BEAM improves HRQoL12. The aims of this trial’s internal pilot were to (1) establish the feasibility of a RCT investigating the effectiveness of Kidney BEAM and (2) explore participants’ perceptions of trial and intervention acceptability. This paper describes the development of Kidney BEAM, and the methods and results of the internal pilot.

Methods

Reporting is informed by relevant CONSORT extensions13,14,15 and reporting guidance for remote trials16 and qualitative research17.

Design

A prospective, mixed-methods, multicentre randomised waitlist-controlled internal pilot trial was conducted. An internal pilot is a phase in a trial after which progress is assessed against pre-specified progression criteria18. Internal pilots are a cost-effective way of assessing whether it is feasible to continue to a definitive trial, as data collected during the internal pilot phase contribute towards the final analyses18. The results may allow trialists to modify the processes used to enhance the chances of successful recruitment and retention, alongside other important feasibility parameters13. All procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The trial was prospectively registered (NCT04872933). Date of first registration 05/05/2021.

Settings and participants

Adults > 18 with established CKD were recruited from five NHS hospitals within the UK. Centres selected were those first open to recruitment. Inclusion and exclusion criteria mirrored the definitive trial (Table 1)12. CKD was defined as kidney damage or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m(2) for 3 months or more, irrespective of cause19.

Recruitment

Routine clinical staff who were engaged in delivering routine care at each hospital site screened medical records to identify eligible participants. Suitable adults were primarily approached via telephone, or face-to-face during routine clinic visits, by trained research staff. Posters were also displayed at each kidney unit, allowing potential participants to contact the trial team if they were interested. Written informed consent was obtained primarily via an online link or face-to-face at a routine clinic visits.

Baseline demographic and clinical variables

In addition to the outcome measures collected (see below), demographic and clinical characteristics were gathered from participant records.

Randomisation

Following baseline assessments, participants were randomised (1:1) to Kidney BEAM or the waitlist control group, using randomly permuted blocks. Randomisation was performed by an independent researcher using a validated web-based system (Sealed Envelope Ltd).

Wait list group

Participants who were allocated to the wait-list control group continued with their usual care and refrained from participating in a structured exercise programme. They were invited to use Kidney BEAM following the end of their involvement in the trial.

Overview of the development of the Kidney BEAM intervention

Initial development phase

The development process, and intervention logic model, are detailed in Supplementary Material 1. Development was informed by INDEX, DHI and co-production guidance20,21,22,23. Fifteen researchers and clinicians with backgrounds in rehabilitation, physical activity, nephrology and digital health, five web developers, six partners from kidney charities (Supplementary Material 1) and six stakeholders with expertise through lived experience of CKD (50% male; 53 ± 17 years; 50% White British; 33% pre-dialysis CKD, 33% dialysis, 33% transplanted) co-produced the intervention. Stakeholders with lived experience volunteered for this role and were engaged via Kidney Research UK networks, or via the hospital sites involved in the trial.

The initial theory-informed development of Kidney BEAM included four iterative stages, which occurred rapidly over four-weeks:

-

1.

Existing evidence and ongoing research were reviewed and matched to the COM-B model within a behavioural analysis24,25,26,27,28,29.

-

2.

Potential levers for change, identified by the behavioural analysis, were linked with intervention functions using the Behaviour Change Wheel30. The affordability, practicality, effectiveness, acceptability, safety, equity (APEASE)29 and contextual fit20 of the proposed functions were considered.

-

3.

Identified functions were linked to appropriate behaviour change techniques using the behaviour change taxonomy31.

-

4.

Participatory co-design23 and user-centred agile software design32 were used to create an intuitive and engaging DHI.

User testing phase

A six-month user testing phase to direct further refinement followed development. This is reported elsewhere7 and summarised in Supplementary Material 1. The final intervention is described in detail in Table 233. Briefly, Kidney BEAM is a digital health intervention (DHI) co-developed with people with CKD to support physical activity and emotional well-being self-management. Kidney BEAM can be accessed via a range of devices (including smartphones) and offers: online live exercise classes modelled on kidney rehabilitation programmes led by a kidney physiotherapist; on-demand exercise videos offering a range of different types of physical activity of varying durations and for different levels of fitness and ability; educational blogs and videos on a variety of topics relating to CKD self-management; virtual groups for peer support; a personalised schedule for booking live classes, organising activities, setting personal goals, and reminders and; a personalised physical activity diary to monitor progress and record off-DHI activity. The materials on BEAM were provided by a wide range of kidney professionals and qualified exercise instructors who themselves were living with CKD.

Participants were encouraged to attend a minimum of twice weekly physical activity sessions, to achieve 150 min/per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 min/per week of vigorous activity, and muscle resistance training on 2 days of the week. All participants had access to the DHI for 12 weeks. At the end of the 12-week programme, participants were encouraged by phone and email to maintain their engagement and self-manage their activity using the DHI.

Sample size

Determinations of sample size around a primary outcome are not relevant to an internal pilot, and sample sizes of 24–50 are considered sufficient34. For the qualitative component, maximum variation sampling was used to ensure diversity35. Primary importance was given to sampling participants with a diverse range of engagement with Kidney BEAM. Fifteen interviews were conducted, with data collection ceasing when information power was sufficient to address the research aims36.

Primary outcome for the internal pilot

Eligibility and recruitment

The feasibility of remote recruitment was established by recording rates of eligibility and recruitment. The demographics of those who declined were also recorded.

Randomisation and baseline assessments

The acceptability of randomisation and remote assessment procedures were explored by examining the proportion of participants withdrawing at each time point by group.

Intervention acceptability

To explore the acceptability of Kidney BEAM, in addition to the qualitative interviews described below, adherence was assessed using the number of sessions (live and on-demand) completed, minutes of physical activity undertaken and the proportion of participants who completed at least one (a key progression criterion) and two (the minimum recommended number) sessions per week over 12 weeks.

Outcome acceptability

Rates of outcome completion were used to determine the ability to collect data remotely at baseline and 12 weeks. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) were gathered using a secure online questionnaire (SurveyMonkey Ltd) (Table 3). Participants also remotely undertook the Sit-to-Stand in 60 Seconds (STS60), a validated measure of muscle endurance37. Blinding of the intervention providers and the participants was not possible. Outcome assessors were, however, blinded to treatment allocation.

Safety and monitoring

All adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded and considered for severity, causality and expectedness.

Assessment of feasibility

For key feasibility outcomes, a priori criteria (Table 4) were used to establish progression to a definitive trial38. For each criterion, ‘stop’ (indicating there were fundamental challenges that may impede a definitive trial) and ‘go’ thresholds (indicating there were no challenges) were established. Results falling between these thresholds indicated that adaptations may render the definitive trial viable38.

Interviews

One-to-one, semi-structured interviews with participants from the intervention group explored their: (i) perceptions of Kidney BEAM and; (ii) experiences of participating in a remote trial. A topic guide (Supplementary Material 2) was developed in advance and piloted during the first three interviews. These initial interviews were retained within the analysis.

Interviews were conducted by experienced qualitative researchers, all of whom had experience of working with people with CKD (HMLY, EMC, RB, JB). Some of the participants may have been aware of the researchers from their role in developing and delivering physical activity and education as part of the DHI. Any influence of these dual roles on the data collection or analysis process was explored via reflexive journals kept by the qualitative research team throughout, creating an ‘audit trail’ of analytical decisions. The involvement of multiple researchers in the analysis and interpretation of the data facilitated discussion on the level of agreement between coders and ensured that analysis and interpretation remained grounded in the data. To enhance credibility, the findings were discussed with the wider multidisciplinary research team and the patient and public (PPI) group. Interviews were conducted at an appointment separate from the trial assessments via telephone or secure online video conferencing software and were audio-recorded. Participants were interviewed as soon as possible following the completion of their involvement in the trial.

Data analysis

Quantitative analyses were performed using SPSS 28 (IBM UK Ltd, UK). Descriptive statistics were used to estimate feasibility outcomes and summarise adverse events13 and are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (IQR) or n (%), as appropriate.

Qualitative analysis was undertaken according to the framework approach39. Transcripts were reviewed and coded line by line. Initial codes were discussed and refined, culminating in an analytical framework that was then systematically applied to the remaining transcripts. A matrix, which summarised the data from each participant by theme, was created. All qualitative researchers kept a diary to enhance reflexivity and rigour39,40. Data management was facilitated using NVivo (QSR International Ltd, version 20) and Excel software (Microsoft Ltd).

Finally, qualitative and quantitative results were merged in a ‘joint display’ to facilitate a comprehensive overall assessment of feasibility and acceptability41. This was used alongside the progression criteria to inform progression to a definitive trial. The suggested adaptations to the intervention were prioritised using the MoSCoW framework, which is a feature of agile software design32. Prioritisation was informed by the APEASE criteria (Supplementary Material 1)29.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

The PPI group involved in development of the intervention were also involved in the conception of the trial, and throughout its conduct.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The internal pilot was part of the definitive kidney BEAM trial and received ethical approval from the UK National Health Service (NHS) Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 21/LO/0243). All participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Results

Feasibility trial

Eligibility and recruitment

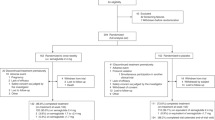

Screening and recruitment occured from May to December 2021, with data collection completed by June 2022. Figure 1 outlines the progression of participants through the pilot trial. Of the 763 adults screened, n = 244 (32%, 95% CI 29 to 35%) were ineligible.

N = 519 (68%, 95% CI 65 to 71%) participants were eligible, but n = 303 (58%, 95% CI 54–63%) did not respond to an invitation to participate by the end of the pilot period. Of the 216 responders, 50 (23%, 95% CI 18–29%) consented. The majority of those who declined did not provide a reason (n = 61, 36%, Fig. 1). Those who declined were similar in demographic to those who participated (Supplementary Material 3).

Cumulative monthly recruitment rates are compared with predicted rates in Fig. 2. Sites recruited a median of 6 (IQR 3–13) participants per month. Of those who consented, n = 8 (16% 95% CI 7–29%) withdrew before randomisation. All withdrew through choice or because they did not attend the baseline remote assessment. Of the n = 42 randomised, n = 22 were allocated to Kidney BEAM and n = 20 to the waitlist control group.

Participant characteristics

At baseline the groups were well-matched, although the control group were older and had more co-morbidity, as assessed using the Charlson co-morbidity index (Table 5). The majority of the sample were White British (n = 29, 69%), and non-frail, as assessed using the Clinical Frailty Scale(n = 42, 100%).

Retention

Seven participants (17%, 95% CI 7–31%) were lost to follow-up; six (14%, 95% CI 5–28%) from the kidney BEAM group and one (2%, 95% CI 0.6–1%) from the waitlist control group. Reasons for withdrawal included kidney transplantation (n = 3), being medically unfit (n = 2) and personal reasons (n = 2).

Exercise adherence

Amongst the remaining participants, a median of 14 (IQR 5–21) sessions were completed, representing a median adherence rate of 58% (IQR 28–86) and a median of 729 (IQR 412–1010) minutes of physical activity over 12 weeks, the equivalent of 61 min per week.Thirteen (59%) participants completed at least 1 session.

Outcome acceptability

At baseline, 90–100% of outcome data (including the primary outcome for the definitive trial) were completed and 62–83% at 12 weeks (Table 6).

Harms

There were no adverse events, serious adverse events or deaths during the pilot.

Qualitative findings

Twenty participants were approached for an interview and fifteen (75%) agreed. Full characteristics are provided in Table 7. Interviews lasted a median of 43 ± 14 min.

Perceptions of participating in a remote trial

Reasons for participation

Illustrative quotes are presented in Table 8. The majority of participants participated due to a pre-existing desire to be active. Many had previously been active, but found this was negatively impacted by lockdown, and Kidney BEAM was a useful ‘kick-starter’ to addressing this. Participants with low to moderate adherence described how a desire to help others and a feeling of indebtedness to their clinical care team were strong drivers to participation.

Experiences of remote recruitment and assessment

Most participants found the online consent process straightforward but felt that telephone and face-to-face follow-up discussions remained important for informed consent. Emphasising the uniqueness and potential benefits of Kidney BEAM via diverse patient stories were suggested methods of increasing recruitment. Several people worried that allocation to the wait list control group would indicate they were not suitable for a physical activity-based intervention.

Remote trial assessments were universally described as simple and quick, and most people had no concerns regarding safety. The main challenges were lack of space and concerns regarding validity. The remote PROMS were less acceptable and described as repetitive, with some of the questions within the KDQoL-SF1.3 perceived as irrelevant.

Preferred methods for dissemination of the results

The majority of participants wanted to be informed about the results of the trial, and how these might impact clinical care. Information should be disseminated via email or video in an accessible manner.

Perceptions of Kidney BEAM

Kidney BEAM within the CKD journey

Kidney BEAM was considered particularly relevant at the start of participants CKD journey. It was viewed as a trusted resource to address knowledge gaps and provide peer support. It was also felt to be useful following kidney transplantation, when participants were open to making lifestyle changes, but where there was a lack of specific guidance around effective and safe physical activity.

Inclusive

Kidney BEAM was described as positively framed and praised for offering standing and seated physical activity options, which allowed people to adapt the sessions to their ability. The video format was helpful for those participants managing fatigue, as it was easier to concentrate and the ability to pause the on-demand videos enabled periods of rest. The opportunity to choose from a wide range of physical activity types was also valued. Participants suggested providing additional CKD and life stage specific content, and more detailed information for people with a good existing understanding (Table 9).

Enhancing the opportunity to be physically active, and the challenge of time

Participants were managing hectic and unpredictable work and caring responsibilities. Those receiving dialysis were additionally managing high levels of treatment and symptom burden. Fatigue was exacerbated by these busy lifestyles and, together with fluctuations in health and ability, this made scheduling physical activity challenging. Kidney BEAM allowed participants to save time by reducing travel and offering flexible opportunities to be physically active. Despite this, they continued to report having limited time to engage with the DHI. Most participants focused on the physical activity sessions and personally relevant educational topics and were unaware of the breadth of content available.

Suggestions for refinement centred around helping participants to maximise their available time. Kidney BEAM could be made easier to navigate, and participants suggested that a short video ‘tour’ and increased telephone or online support would also help. They also felt it was important to highlight new content and provide guidance on key content. Shorter session durations, a more extensive live class timetable and greater leeway with live class bookings were also suggested (Table 10).

Enhancing motivation to be physically active

Despite the challenges with attending the live classes due to lack of time, those able to attend found them highly engaging. The instructors were perceived as warm, inclusive and knowledgeable. Areas for enhancement included making the relevance of increased physical activity on CKD more evident and offering one-to-one reviews. Participants with higher adherence underlined the importance of the community and accountability created by the live classes, which fostered ongoing participation. Text message reminders, mandating more than two classes per week, and using personal goals were highlighted as methods for further enhancing accountability. People with lower adherence were more likely to describe feeling self-conscious.

The physical activity diary was described as a motivational means of tracking progress and increasing ‘offline’ physical activity. Participants felt the ability to sync the diary with wearable monitors would reduce burden. Introducing summary analytics to help them understand how their physical activity levels are influenced by factors such as symptoms and time of the day was also suggested to support activity planning.

External support for Kidney BEAM

Other sources of support and motivation were family, friends and the Kidney BEAM team. Many participants completed the sessions alongside a family or friends and had subsequently been encouraged by them to engage in offline physical activity.‘Check-ins’ by the Kidney BEAM team were also described as supportive and useful for increasing accountability (Table 11).

Integrated mixed methods analyses

Integrated analyses highlight that the ‘go’ criterion for progression to the definitive trial was met for outcome acceptability, alongside the ‘change’criteria for recruitment, intervention acceptability and retention. Quantitative and qualitative analyses were both complementary and confirmatory, indicating that progression to the definitive trial would be feasible and that Kidney BEAM is acceptable, following adaptations to increase recruitment, reduce loss to follow-up and promote increased engagement. The integrated analysis and the planned adaptations to the trial and intervention are outlined within Table 12, with the rationale for suggested intervention refinements included within in Supplementary Material 4.

Discussion

The results of this pilot trial suggest that progression to a definitive trial is warranted, provided adaptations are made to enhance recruitment and retention rates. The progression criterion for outcome acceptability was achieved and there were no adverse events. Feedback regarding the acceptability of Kidney BEAM was positive, with suggested refinements focused on supporting people maximise their available time.

This trial is the first to demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of a physical activity and emotional well-being DHI for people with CKD. The pre-specified progression criteria supported continuation and identified adaptations to enhance recruitment and retention. The recruitment rates observed in this trial are lower than those seen in other multi-centre trials of physical activity programmes delivered across the CKD spectrum, which range from ~ 41 to 69%42,43,44. The reason for this discrepancy is likely due to these trials using face to face recruitment, rather than remote, recruitment and the interventions being highly structured and supervised, rather than delivered entirely online. Importantly, these interventions have failed to have been widely implemented within routine practice because the workforce and expertise required to do this are not routinely available to people with CKD45. When compared with other trials of self-management and physical activity DHIs for long-term conditions, rates of refusal within this pilot are comparable (also ~ 32%)46. Optimising the recruitment for Kidney BEAM and ensuring the wide reach and acceptability of this intervention, using the learning gathered from this internal pilot and the subsequent definitive trial, will ensure that safe, scaleable and effective physical activity and self-management intervention may be delivered to a demographically and geographically diverse population, bridging this significant translational gap.

Notably, the trial was also conducted during the pandemic, when many centres were not actively recruiting to trials. This undoubtedly contributed to the lower-than-expected recruitment rates. Trials planned during this time required protocols that were safe and deliverable, whilst also maintaining scientific validity and integrity47,48. A shift to remote trial delivery increased exponentially during this period, paving the way for more remote trials in the future. The results of our trial demonstrated challenges with converting potential participants into enrolees, supporting the findings of a recent systematic review, where conversion rates were higher in those recruited ‘offline’, and in some cases led to the recruitment of ‘atypical’ populations49. Existing evidence recommends a combination of on, and offline recruitment be used to derive a representative sample49 and a tool kit for remote trial delivery has been published since the inception of the Kidney BEAM trial, recommending staff training, follow-up and support for participants being recruited online47. The learning from the pilot has led to several adaptations to the recruitment process which are outlined in Table 12. The adaptations needed to achieve the required sample size for the definitive trial included: the addition of further centres, following-up non-responders, and a script to support the recruitment of people not already contemplating becoming more active (Supplementary Material 5). Similar recruitment strategies are effective in trials of DHIs in other long-term conditions10 and may also address the high rates of non-responders and post-randomisation withdrawals.

Similarly, retention rates did not reach our a priori criteria. We were not able to explore this further within the interviews, which were conducted with participants who completed the trial. Other studies have reported similar challenges, and rates of retention of around 48%, within online trials and DHIs50,51. Considering this, our retention rate of 70% compares favourably, particularly for a physical activity intervention which requires significant engagement and motivation. Loss to follow up in online trials and digital interventions appears to be positively influenced by a range of factors including referral from a clinical team member, targeting motivated participants, incentivisation, nudges and reducing study complexity50,51. These strategies may be employed to increase retention, but must be balanced with the potential dangers of selecting participants which are not representative of all people with CKD.

The baseline characteristics of those recruited were largely representative of the UK CKD population52, providing reassurance relating to the potential external validity of the definitive trial. Whilst the demographics of those who declined were similar to those who participated, frailer participants were not recruited. The incidence of frailty is approximately 75% within the CKD population53 and physical activity is an important component of frailty management54. Physical activity DHIs for frail older people are effective55 and Kidney BEAM may represent an important intervention for this particularly vulnerable group, but it remains uncertain whether the challenges to recruiting this group are reflective of the acceptability of Kidney BEAM, or because the research teams inadvertently acted as gatekeepers to the trial, as has been observed in other trials10.

Kidney BEAM was well received due to its inclusivity, accessibility and flexibility. Similar findings have been reported in DHIs for other long-term conditions, where choice over how and where support is accessed increased a sense of control and reduced anxiety8,10. Kidney BEAM also increased participants’ opportunity and motivation to be physically active, however, lack of time continued to be the predominant ongoing barrier to engagement. Competing priorities has been highlighted as a major barrier to engagement with DHIs in other long-term conditions10. Although the ‘go’ criteria for intervention acceptability was not achieved, adherence to kidney BEAM (58%) compared favourably with physical activity DHIs for other long-term conditions (55%)56 and face-to-face renal rehabilitation programmes (59%)57.

Suggested refinements focused on further enhancing participants’ opportunity and motivation to engage, via individual tailoring. Allowing users to create personalised goals, customise the level of the information within the DHI and receive personalised reminders, have all been shown to increase engagement and effectiveness in other long-term conditions8,56 and DHIs for people with CKD9. DHIs lend themselves well to tailoring10, and the feedback received from participants will be used to further personalise the content on Kidney BEAM in the future. The physical activity diary and goal-setting features were valued for helping participants track personal progress. Enhancing this by syncing the diary with wearable activity trackers and providing personal analytics has been shown to increase adherence across a range of other long-term conditions by supporting users to gain new understanding about how to manage their condition, whilst also reducing burden10,56.

Participants highlighted that ease of use was key to increasing meaningful engagement. Intuitive and easy-to-use DHIs are important for securing initial engagement8,10 and sustained use over time56. In a similar manner to recruitment to the trial, healthcare professional support was also important for the delivery of the DHI, with engagement highlighted as important sources of motivation. The integration of healthcare professional support with DHIs has been consistently associated with increased adherence in other long-term conditions56, via increased self-confidence, development of skills and reduced isolation56,58.

The community created via Kidney BEAM was an important motivator for some participants, but less appealing to others. This ambivalence has been observed in other trials and is related to individual preferences8,56 Kidney BEAM allowed participants to select an option which suited their personal preferences, enhancing acceptability and reducing the potential for negative social comparison56. Interestingly, family and friend support was also crucial for many participants, which was not anticipated in the development phase. Previous research suggests that targeting these wider support networks is important to increasing uptake10 and the results of this current trial indicate that it can also promote ‘offline’ activity outside of the DHI.

Strength and limitations

To our knowledge, this trial is the first to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a remote trial of a CKD-specific DHI focused on physical activity and emotional well-being. A key strength is a strong emphasis on the co-production of the intervention using established, theory-informed approaches which have previously been lacking within this field9. An acknowledged limitation is the lack of exploration of the views of researchers and withdrawing participants which would have provided further useful insight.

One of the reasons the ‘go’ criteria may also not have been achieved was that not all people may have been able to access and use an English language DHI. Existing reviews indicate that although DHIs may lead to improvement in clinical outcomes across a range of long-term conditions, they are most often utilised by digitally and health literate people with access to technology10,59. Up to 20% of the general population do not possess fundamental digital skills, resources, motivation and confidence needed to effectively use DHIs8,10,60. Digital exclusion can perpetuate health inequality60 and, given that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the introduction of DHIs with routine care59, exploration of digital exclusion in relation to online physical activity and emotional wellbeing self-management programmes is warranted. Not all patient populations are affected in the same way, or experience the same barriers, making understanding the perspectives of those who do not participate in the trial particularly important60,61. Strategies that have proven beneficial to engaging frailer participants in other evaluations of DHIs include providing access to technology, providing support to increase ‘readiness’ to use the intervention, addressing concerns about injury, social isolation and security and avoiding stigmatisation62,63. As part of the evaluation of Kidney BEAM, we are conducting a qualitative sub-study12 which will explore these challenges in people who declined to participate in the trial. The findings of this sub-study, alongside a substudy specifically examining the role and effectiveness of Kidney BEAM during the intradialytic period for people receiving HD, will more comprehensively inform strategies to address inequality of access and to improve the reach of Kidney BEAM.

Additionally, some of the qualitative researchers were known to the participants from their roles as physiotherapists delivering the classes or as the Principal Investigator at one of the sites. Although this may have influenced their responses, this risk was mitigated by ensuring participants were interviewed by a researcher unknown to them. In some instances, these dual roles were helpful, as knowledge of the trial and DHI allowed researchers to provide further prompts and explanations.

Conclusion

A definitive trial to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of Kidney BEAM feasible, with adaptation to increase acceptability. The results of this definitive trial will provide robust evidence for the role of DHIs in supporting physical activity and self-management in people with CKD. This will address an area of unwarranted variation in care and potentially lead to a step change in the clinical management of this population.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse events

- APEASE:

-

Affordability, practicality, effectiveness, acceptability, safety, equity

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DHI:

-

Digital health intervention

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- MoSCoW:

-

Must have, should have, could have and would like

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- PPI:

-

Patient and public involvement

- PROMS:

-

Patient reported outcome measures

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse events

- STS60:

-

Sit-to-stand in sixty seconds

References

Bikbov, B. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395(10225), 709–733 (2020).

Fletcher, B. R. et al. Symptom burden and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 19(4), e1003954 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Therapeutic effects of exercise interventions for patients with chronic kidney disease: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMJ Open 12(9), e054887 (2022).

Jeddi, F. R., Nabovati, E. & Amirazodi, S. Features and effects of information technology-based interventions to improve self-management in chronic kidney disease patients: A systematic review of the literature. J. Med. Syst. 41, 1–13 (2017).

Greenwood, S. A. et al. Exercise counselling practices for patients with chronic kidney disease in the UK: A renal multidisciplinary team perspective. Nephron Clin. Pract. 128(1–2), 67–72 (2014).

Kyaw, T. L. et al. Cost-effectiveness of digital tools for behavior change interventions among people with chronic diseases: Systematic review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 12(1), e42396 (2023).

Mayes, J. et al. The rapid development of a novel kidney-specific digital intervention for self-management of physical activity and emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: Kidney Beam. Clin. Kidney J. 15(3), 571–573 (2022).

Taylor, M. L. et al. Digital health experiences reported in chronic disease management: An umbrella review of qualitative studies. J. Telemed. Telecare 28(10), 705–717 (2022).

Stevenson, J. K. et al. eHealth interventions for people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012379.pub2 (2019).

O’connor, S. et al. Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 16, 1–15 (2016).

Antoun, J. et al. Understanding the impact of initial COVID-19 restrictions on physical activity, wellbeing and quality of life in shielding adults with end-stage renal disease in the United Kingdom dialysing at home versus in-centre and their experiences with telemedicine. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(6), 3144 (2021).

Walklin, C. et al. The effect of a novel, digital physical activity and emotional well-being intervention on health-related quality of life in people with chronic kidney disease: Trial design and baseline data from a multicentre prospective, wait-list randomised controlled trial (Kidney BEAM). BMC Nephrol. 24(1), 122 (2023).

Eldridge, S. M. et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 355, i5239 (2016).

Boutron, I. et al. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann. Internal med. 167(1), 40–47 (2017).

Eysenbach G, Group C-E. CONSORT-EHEALTH: Improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 13(4), e1923 (2011).

Research NIoH. Remote trial delivery 2022. https://sites.google.com/nihr.ac.uk/remotetrialdelivery/home (Accessed December 2022).

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19(6), 349–357 (2007).

Herbert, E., Julious, S. A. & Goodacre, S. Progression criteria in trials with an internal pilot: An audit of publicly funded randomised controlled trials. Trials 20(1), 1–9 (2019).

Levey, A. S. et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 67(6), 2089–2100 (2005).

O’Cathain, A. et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 9(8), e029954 (2019).

West, R. & Michie, S. A Guide to Development and Evaluation of Digital Behaviour Interventions in Healthcare (Silverback Publishing, 2016).

NIHR. Guidance on co-producing a research project. https://www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/?opportunity=nihr-guidance-on-co-producing-a-research-project (2021).

Clemensen, J. et al. Participatory design in health sciences: Using cooperative experimental methods in developing health services and computer technology. Qual. Health Res. 17(1), 122–130 (2007).

Zeng, J. et al. The exercise perceptions of people treated with peritoneal dialysis. J. Renal Care 46(2), 106–114 (2020).

Barriers and facilitators for engagement and implementation of exercise in end‐stage kidney disease: Future theory‐based interventions using the behavior change wheel. Seminars in dialysis (Wiley Online Library, 2019).

Clarke, A. L. et al. Motivations and barriers to exercise in chronic kidney disease: A qualitative study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 30(11), 1885–1892 (2015).

Castle, E. M. et al. Usability and experience testing to refine an online intervention to prevent weight gain in new kidney transplant recipients. Br. J. Health Psychol. 26(1), 232–255 (2021).

Billany, R. E. et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators to exercise in kidney transplant recipients: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 25(2), 764–774 (2022).

Michie, S., Atkins, L. & West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions 1st edn, 1003–1010 (Silverback Publishing, 2014).

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. sci. 6(1), 1–12 (2011).

Michie, S. et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 46(1), 81–95 (2013).

Brhel, M. et al. Exploring principles of user-centered agile software development: A literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 61, 163–181 (2015).

Hoffmann, T. C. et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687 (2014).

Sim, J. & Lewis, M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65(3), 301–308 (2012).

Ritchie, J. et al. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers (Sage, 2013).

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D. & Guassora, A. D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 26(13), 1753–1760 (2016).

Ozalevli, S. et al. Comparison of the Sit-to-Stand Test with 6 min walk test in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Med. 101(2), 286–293 (2007).

Avery, K. N. et al. Informing efficient randomised controlled trials: Exploration of challenges in developing progression criteria for internal pilot studies. BMJ Open 7(2), e013537 (2017).

Gale, N. K. et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13(1), 1–8 (2013).

Tracy, S. J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inquiry 16(10), 837–851 (2010).

Creswell, J. W. & Clark, V. L. P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (Sage publications, 2017).

Anding-Rost, K. et al. Exercise during hemodialysis in patients with chronic kidney failure. NEJM Evid. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2300057 (2023).

Manfredini, F. et al. Exercise in patients on dialysis: A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 28(4), 1259 (2017).

Hellberg, M. et al. Randomized controlled trial of exercise in CKD—The RENEXC study. Kidney Int. Rep. 4(7), 963–976 (2019).

Ancliffe, L. C. E., Wilkinson, T. & Young, H. M. L. The Stark Landscape of Kidney Rehabilitation Services in the UK: Is the kidney Therapy Workforce Really a Priority? (UK Kidney Week, 2023).

Gorst, S. L. et al. Home telehealth uptake and continued use among heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A systematic review. Ann. Behav. Med. 48(3), 323–336 (2014).

Masoli, J. A. et al. A report from the NIHR UK working group on remote trial delivery for the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Trials 22(1), 1–10 (2021).

McDermott, M. M. & Newman, A. B. Remote research and clinical trial integrity during and after the coronavirus pandemic. JAMA 325(19), 1935–1936 (2021).

Brøgger-Mikkelsen, M. et al. Online patient recruitment in clinical trials: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22(11), e22179 (2020).

Daniore, P., Nittas, V. & von Wyl, V. Enrollment and retention of participants in remote digital health studies: Scoping review and framework proposal. J. Med. Internet Res. 24(9), e39910 (2022).

Pratap, A. et al. Indicators of retention in remote digital health studies: A cross-study evaluation of 100,000 participants. NPJ Digit. Med. 3(1), 21 (2020).

Registry UR. UK Renal Registry 24th Annual Report—Data to. https://ukkidney.org/audit-research/annual-report (Accessed 31 December 2020) (2022).

Wilkinson, T. J. et al. Associations between frailty trajectories and cardiovascular, renal, and mortality outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13(5), 2426–2435 (2022).

Silva, R. et al. The effect of physical exercise on frail older persons: A systematic review. J. Frailty Aging 6(2), 91–96 (2017).

Solis-Navarro, L. et al. Effectiveness of home-based exercise delivered by digital health in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 51(11), afac243 (2022).

Jakob, R. et al. Factors influencing adherence to mHealth apps for prevention or management of noncommunicable diseases: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 24(5), e35371 (2022).

Greenwood, S. A. et al. Evaluation of a pragmatic exercise rehabilitation programme in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27(suppl_3), iii126–iii34 (2012).

Shen, H. et al. Electronic health self-management interventions for patients with chronic kidney disease: Systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J. Med. Internet Res. 21(11), e12384 (2019).

Stauss, M. et al. Opportunities in the cloud or pie in the sky? Current status and future perspectives of telemedicine in nephrology. Clin. Kidney J. 14(2), 492–506 (2021).

Unit TS. Improving Digital Health Inclusion: evidence scan 2020. https://www.strategyunitwm.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/2021-04/Digital%20Inclusion%20evidence%20scan.pdf (Accessed 29th March 2023).

Herrera, S., Salazar, A. & Nazar, G. Barriers and supports in eHealth implementation among people with chronic cardiovascular ailments: Integrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(14), 8296 (2022).

Linn, N. et al. Digital health interventions among people living with frailty: A scoping review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 22(9), 1802–1812 (2021).

Mitchell, U. A., Chebli, P. G., Ruggiero, L. & Muramatsu, N. The digital divide in health-related technology use: The significance of race/ethnicity. Gerontologist 59(1), 6–14 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the work of the various research teams at each site and thank all the participants involved in this research. This research was prospectively registered NCT04872933.

Funding

This trial was funded by a grant from Kidney Research UK. Funding for Kidney Beam is currently supported by the four major UK charities: Kidney Research UK, Kidney Care UK, National Kidney Federation and the UK Kidney Association. HMLY is funded by the NIHR [NIHR302926]. Part of this research was carried out at the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, or writing of this protocol.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authorship followed ICMJE guidelines. S.G., H.M.L.Y., R.E.B., N.B., J.B., E.M.C., Z.L.S., H.N., A.H, K.B., A.C.N., M.P.M.G.-B., T.J.W. and J.M. were responsible for the inception and design of the project. S.G., H.M.L.Y., R.E.B., N.B., J.B., E.M.C., C.W., A.H., K.B., V.D., L.H., H.N., A.C.N., T.W., N.B., J.C., N.C., S.B., J.B., P.K., P.A.K., D.W., J.T, M.J., M.W.T., C.S., J.B., E.A., K.M., Z.L.S., M.P.M G.-B., T.J.W., H.W., J.M. and all made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript text, tables, figures and supplementary material. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. HMLY has had full access to the data in the trial and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

King’s College Hospital NHS Trust and SG were involved in the conception and development of Kidney Beam. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, H.M.L., Castle, E.M., Briggs, J. et al. The development and internal pilot trial of a digital physical activity and emotional well-being intervention (Kidney BEAM) for people with chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 14, 700 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50507-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50507-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.