Abstract

Based on the concept of service-dominant logic as the emerging organizing logic of marketing that would replace the traditional goods-dominant view, Vargo and Lusch (2004) originally proposed that among several other approaches to research and marketing practice that had emerged, relationship marketing would be subsumed by this broader view. More recently, however, Vargo (2009) suggested that because relationship marketing focuses on increasing the series of on-going transactions with a customer, coupled with the goal of enhancing their long-term patronage, that relationship marketing extends the goods-dominant perspective, rather than transcending into the service-dominant logic. This article counters that the relationship marketing view of the customer has already transcended the goods-dominant view to the to service-dominant view based on the way that customers are brought into the relationship as active participants in the service creation, and act as “co-producers” of value. To address the apparent goods-dominant approach in two widely used relationship marketing practices and measures, customer relationship management and customer lifetime value, this article proposes that these tools can be used from a goods-dominant view, but they can also serve as essential steps towards the practice of relationship marketing from the service-dominant logic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

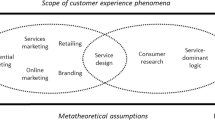

In the seminal article that introduced the concept of “Service-Dominant Logic” as shift in perspective as the organizing approach to marketing, Vargo and Lusch (2004) proposed that marketing is evolving to a “new dominant logic” that subsumes what they identified as seven developing separate lines of thought towards marketing as a “social and economic process.” These lines of thought have developed around various themes such as market orientation, services marketing, relationship marketing, quality management, network analysis, and so on, and these occurred where academic researchers found the goods-dominant (G-D) perspective of marketing lacking in its ability to explain the phenomena that was being investigated. Among these approaches to marketing is “relationship marketing.” While only one of seven lines of thought used in the development of the service dominant (S-D) view, the concept of the relationship is critical to its understanding. The S-D logic proposes that, “marketing has moved from a goods-dominant view, in which tangible output and discrete transactions were central, to a service-dominant view, in which intangibility, exchange processes, and relationships are central” (Vargo and Lusch 2004, p. 2, italics added). Thus, the S-D perspective relies on relationship marketing for some of its fundamental ideas or propositions (FPs), particularly where the firm-customer relationship is considered.

In more recent work on the S-D perspective, Vargo (2009) examines practices and concepts that have been derived from relationship marketing, such as customer lifetime value (CLV) and customer relationship management (CRM), and sees these—through their focus on repeat patronage—as being at least to some degree anchored in the G-D logic. From this basis, he questions the degree to which relationship marketing can evolve into the S-D logic, and if there is a higher-order relationship conceptualization that can transcend its traditional understanding that is rooted in the G-D logic (Vargo 2009, p. 373).

In this article, we address these two questions by focusing on the relationship marketing view of the customer. First, we examine the degree to which the primary logic of relationship marketing is consistent with and can be the S-D logic compatible. Second, we examine the practices of relationship marketing that appear to be anchored in the G-D logic, particularly CRM and CLV, and examine the degree to which these could be prerequisites for co-production and co-created value, and thereby contribute to Vargo’s quest for “a higher-order, S-D logic-compatible relationship conceptualization.”

The Goods-Dominant and Service-Dominant Logic Perspectives of the Customer

To understand the S-D view of the customer, it is best to contrast it with the G-D view. In the goods-centered approach to marketing, customers are acted on (marketers segment them, distribute to them, promote to them, satisfy them). From a perspective of value, the value of a good is contained in the good itself, and the key focus is on the exchange, i.e., value for value: the good in exchange for money (assuming a monetary and not a barter economy). At the point of exchange, the good is handed off to the customer who then consumes it, thus consuming or destroying the value inherent in the good. Whether or not the customer purchases the good in a single transaction, or repurchases many times, the focus remains on the exchange of value for value at a specific point in time (or multiple points of time). Through market research, the firm seeks to improve the value of the good by enhancing customer satisfaction though product improvements, price improvements, place improvements, or information and communication improvements. It is important to note that the good does not have to be a physical item, but can be services such as car repair, manicure, or tax return. In summary, in the G-D approach, the customer is “acted-upon.” Another particular limitation of the G-D approach to the customer is that it assumes that the dyadic nature of the relationship is self-contained, i.e., party 1 acts upon, or interacts with party 2. This narrow view does not consider the networks surrounding the firm and the customer that affect and are affected by the relationship.

The S-D view takes a very different approach to the customer. Vargo (2009, p. 374) notes that “the central tenet of S-D logic is that service is the fundamental basis for exchange.” It is important to clarify the term “service,” which is the application that is rendered from the offering, and contrast that with the category of offers that are called “services” generally due to their intangible nature (like the car repair or manicure mentioned previously). The service that is rendered is seen as a collection of resources available to the customer who then adds and blends the resources provided by the seller, which in combination provides a benefit or a service to the customer and the seller. This collection of resources brought together by the seller and the customer includes an entire network of resources that have already been working to produce value, and in their meeting are transformed to create new value in the form of service to both the seller and the customer. In the S-D view of Vargo and Lusch (2004), the customer functions as an active participant in the creation of value, and in doing so becomes a co-producer of the service that is also being consumed. This point is crucial because, as Vargo (2009, p. 374) states, “in S-D logic, the firm cannot create value, but only offer value propositions (FP7) and the collaboratively create value with the beneficiary (FP6),” (note that the terms FP6 and FP7 will be described below). In the SD view, value is customer determined and this is consistent with the dominant view of value being defined as a calculation by the customer of benefits proportional relative to costs (Kotler 2003).

From a relationship perspective of the firm and the customer, in the S-D logic of marketing, “the customer is primarily an operant resource. Customers are active participants in relational exchanges and co-production” (Vargo and Lusch 2004, p. 7). They continue, “The service-centered view of marketing perceives marketing as a continuous learning process that involves…cultivating relationships that involve the customers in developing customized, competitively compelling value propositions to meet specific needs” (p. 5). Vargo (2009, p. 375) summarizes, “It is through these joint, interactive, collaborative unfolding and reciprocal roles in value creation that S-D logic conceptualizes relationship.”

The S-D logic is captured in ten foundational premises, or FPs (Vargo and Lusch 2004, 2008). While the notion of the customer relationship is imbedded in all of the ten FPs, three of the ten FPs of the S-D logic directly address the customer relationship and need to be stated in order to compare the RM view of the customer with the S-D view of the customer. These include (quoted from Vargo and Lusch 2004, pp. 10–12):

-

FP6: The Customer is Always a Coproducer of Value

-

The customer is always involved in the production of value.

-

In using the product, the customer is continuing the marketing, consumption, and value-creation and delivery processes.

-

The customer becomes primarily an operant resource (coproducer) rather than an operand resource (target) and can be involved in the entire value and chain.

-

-

FP7: The enterprise cannot deliver value, but only offer value propositions

-

Instead of being embedded in goods, value emerges for customers through use and is perceived by customers. The firm cannot create value alone.

-

-

FP8: A Service-Centered View is Customer Oriented and Relational

-

Even if the firm or the customer does not desire multiple transactions, neither are freed from the relationship.

-

The above summarize and provide the basic view of SD logic and the customer. To compare this view of relationship with the view of RM, a complex array of definitions of RM need to be examined.

The RM View of the Customer

The RM view of the customer has been confusing because of the multitude of definitions of relationship marketing. Here are a few that represent typical but various perspectives. Each of these contribute to some degree to Vargo’s (2009) question regarding the ability of a RM conceptualization to be S-D logic compatible.

-

Relationship Marketing refers to all marketing activities directed toward establishing, developing, and maintaining successful relational exchanges (Morgan and Hunt 1994). In this view, the customer is being acted upon by a set of marketing activities focused on multiple, repetitive exchanges.

-

Relationship Marketing is attracting, maintaining, and enhancing customer relationships (Berry 1983). This definition emphasizes the quality and duration of the relationship with the customer.

-

Relationship Marketing is part of the developing “network paradigm” that recognizes that global competition occurs increasingly between networks of firms (Thorelli 1986). This view emphasizes the role of the customer as co-producer of value in supply chains.

-

It is the creation and retention of profitable customers through ongoing collaborative business and partnering activities between a supplier and a customer on a one-to-one basis for the purpose of creating better customer value at reduced cost (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1995b). While this view emphasizes the co-producing nature of the relationship, it focuses on the dyadic nature of a firm and a customer.

Based on this sampling of definitions of relationship marketing—from individual customer relationships (Berry) to global networks (Thorelli)—one can draw the conclusion similar to Vargo’s (2009) that RM is rooted in a G-D perspective, while based on the co-producing nature, RM has elements of the S-D logic FPs outlined in the previous section.

Such confusion was at the center of an exchange between Gruen (1997) and Petrof (1997). In opposing articles, Petrof argued that RM was a mere restatement of the marketing concept, while Gruen argued that RM was distinct from the marketing concept in both theory and practice. Placed in the context of the SD logic today, this argument would be stated differently in current terms. Petrof’s arguments would mirror Vargo’s (2009) concerns that RM is anchored in G-D view, and thus is not different from the established marketing concept (Webster 1992). Gruen’s views would suggest that the fundamental aspects of RM theory and practice are distinct and clearly fit the S-D logic.

Similar to the way Vargo and Lusch (2004) distinguished G-D from S-D, Gruen (1997) distinguished transaction marketing from relationship marketing by both the way value is created and by the type of relationship. He argues that in the transaction approach, competition and self-interest are drivers of value creation, and that marketing efficiency is gained through an arms-length relationship, even while the customer is considered the nucleus of business decision making, a key principle of the marketing concept. In practice, improved manipulation of the marketing mix would lead to sustainable competitive advantage through enhanced customer satisfaction. Alternatively, the relationship orientation developed as the assumptions of the transaction approach were being challenged. Gruen (1997, 33) states, “the axiom that held competition and self-interest as the drivers of value creation was being challenged by the notion of interdependence and cooperation as more efficient and effective at creating value. Founded on this notion of interdependence and cooperation, relationship marketing developed as a business strategy paradigm that focuses on the systematic development of ongoing, collaborative business relationships as a key source of sustainable competitive advantage.”

He continues (p. 34), “Relationship marketers consider value creation a fundamental concept upon which strategic competitive advantage is built. Previously, value was considered to be created by the supplier and then determined in the exchange with the buyer. Under the marketing concept, the job of marketing is to satisfy a customer through the value obtained in the exchange (transaction). In relationship marketing, however, supplier and customer organizations recognize that though interdependent, collaborative relationships, they are able to create greater value than they can through independent arm’s-length exchanges. Proctor & Gamble and Wal-Mart, for example, have joined hands to clash the overall costs of production, distribution, and inventory. Such value is passed along to the consumer who rewards the companies with loyal patronage.”

In summary, there are three general clusters of the view of the customer in RM. The first is clearly G-D anchored as it focuses on increased profit to the firm by focusing on maintaining and enhancing relationships with existing customers. The second in somewhat mixed between a G-D anchoring and the S-D logic, as it focuses on providing improved value to the customer through better understanding of customer needs, but the customer is involved to some degree in this process. Examples of this cluster are customer-specific co-developed products, such as those produced by Bosch for Mercedes-Benz, and aligned business processes, such as the Proctor & Gamble/Wal-Mart described above. The third cluster is anchored in the S-D logic, and it involves the co-creation of customer value through the involvement with the selling firm and/or its offering.

The Paradox of RM and the S-D View of the Customer

As the above discussion shows, there is clearly good reason that Vargo (2009) questions the ability of RM to find its place as the marketing evolves to the SD view. As Vargo (2009) states, RM has gravitated towards a prescriptive imperative with a focus on long-term relationships with repetitive transactions, which is anchored in G-D logic. The focus of RM is often on maximizing repeat patronage, as customers consolidate and become more scarce, and the cost of serving existing customers is viewed as being clearly lower than the cost of acquiring new customers. This is seen as a unidirectional, firm-centric approach where measures include such terms as share of wallet, retention rates, and customer lifetime value (CLV). In practice, this view of RM is manifested in customer relationship management (CRM), which will be described in more detail later. Thus, Vargo (2009) argues that RM has become an extension of the customer orientation, maintaining firm-customer bonds (Dwyer et al. 1987), and governed by relational norms (Morgan and Hunt 1994), which is a G-D approach. Moreover, Vargo (2009) sees RM as focusing on the dyad of the seller and the customer, whereas the S-D view sees relationships as being nested in networks and occurring between networks of relationships. He concludes (p. 374), “As RM has developed, it has increasingly gravitated toward a prescriptive imperative—to foster long term associations resulting in repetitive transactions.” To evolve into S-D logic, RM needs a higher-order S-D logic-compatible conceptualization.

Relationship Marketing and Coproduction of Value

The notion of viewing customers as co-producers has long been a well-established foundation of RM thought (Gummesson 1987). In RM practice, involving the customer into increasingly greater co-production roles has been a strategy that many successful firms have followed, lowering costs through joint planning and shared tasks. In doing so, they have given up traditional activities provided for the customer, and required the customer to absorb these roles. A customer that learns the processes of the supplier firm not only lessens the need for the supplier to be involved with the customer’s activities, but the customer may also assist other customers learning the processes through networking, both on-line (communities) and off-line (user meetings) (Gruen et al. 2006). As such, the value equation (benefits less costs) would seem to indicate that some costs of the customer would increase, thus decreasing value. One would think that customers would not appreciate having extra work to obtain what they need, but that has not been the case. Apparently the benefits of joint production, control, and customized outputs appear to outweigh the extra costs of learning and involvement, increasing the value to the customer. This reconfiguration of roles along the value chain allows for the various economic actors to work together to co-produce value (Normann and Ramirez 1993).

As an example or this reconfiguration of roles, in the airline industry, loyalty of frequent flyers remains crucial. These customers are generally more time sensitive than price sensitive, providing major airlines higher profits. The primary rewards offered to these customers in exchange for their loyalty (assuming the basic service level has been met, such as safety, schedules, destinations, and general on-time performance) are convenience benefits and preferential treatment benefits (Gwinner et al. 1998). The top customer groups for airline, normally referred to as “elite” level frequent fliers, are offered preferential treatment as the primary reward in exchange for their loyalty. For the elite group, airlines offer the advantages of going to the front of the line, preferred seating in the roomy exit rows and near the front of the aircraft, and the opportunity of an upgrade to First Class. However, these elite customers also must do more work for themselves to coproduce this value. These customers can book a reservation directly on the airline’s web site, check-in, and print their boarding pass before leaving for the airport. The first airline employee they need to interact with is at the gate when they are ready to get on board, and even some airlines now provide automated self check-in at the gate. The airline has effectively shifted multiple work tasks previously performed by an airline employee onto the customer, who expends more personal effort while being involved with the airline’s web site, and subsuming other processes that were previously handled by airline personnel. However, rather than receiving less value (assuming the extra work is viewed as an increased cost), the customer is now an active participant in the service creation, and with the added responsibility and sense of control, obtains more value through co-production than when being “acted upon” by a customer service agent.

The concept of partnering with customers that has grown out of relationship marketing. Rackham et al. (1995) present a three component model of partnering based on their research. These components include impact, intimacy, and vision. Each of these is considered to be bilateral and jointly shared. Impact involves specific value that will be formed when the partnership is established, intimacy involves sharing of information, and vision needs to be jointly created and understood as initiator and the long-term driver of the partnership. In the partnership view, interdependence and cooperation replace arms-length antagonism, enabling joint, trust-based collaboration to drive new value. For example, Eaton, a supplier of gas valves and Whirlpool partnered to develop a new gas stove (Rackham et al. 1995). In a traditional approach, Whirlpool would ask Eaton and other suppliers to submit a bid for the job and then select the best supplier based on criteria established for the bidding process. Eaton focused its marketing activities to build a relationship with Whirlpool so that they could become a partner through all the design and production processes of the new stove. By reshaping organizational boundaries and coordinating design teams of both companies to jointly work together, the new stove came to market several months faster that if Whirlpool had relied on its own design capacity. Moreover, a long and expensive search for a supplier was eliminated. While Whirlpool gave up the ability to guarantee lowest price, they gained the ability to slash costs and time to market through the partnership with Eaton. This example shows how the concept of the partnership derived in RM fits the S-D logic.

This reconfiguration of roles provides new ways for value to be created. In the language of S-D logic FP7, this provides new ways that the enterprise can offer “…value propositions that strive to be better or more compelling than competitors” (Vargo and Lusch 2004, p. 11). From the basic understanding that value is a calculation by the customer of benefits less costs, the new value propositions that can be offered provide new means of increasing benefits or lowering costs. Another example here is furniture retailer IKEA who has shifted traditional tasks of furniture manufacturers and retailers to the shoppers to provide a different set of value propositions from their competitors. As Normann and Ramirez (1993, p. 67) state, “IKEA wants its customers to understand that their role is not to consume value, but to create it…IKEA invents value by enabling customers’ own value-creating activities” (italics in original). As the above examples and discussion shows, the RM view of value creation is consistent with S-D logic FP6 with the customer viewed as always a co-producer.

Relationship Marketing and Organizational Structure of Marketing

In order to implement the S-D logic approach where the customer is always a co-producer, the way that firms organize for marketing must support this approach. The organization of marketing in the firm that has been developed in the RM view supports the S-D logic by distributing the role of marketing throughout the organization. Gummesson (1996) espoused the idea that in the RM view, everyone in the organization should be considered a “part-time marketer.” And indeed, we have seen huge changes in firms to implement a customer-focused perspective that pervades the entire organization. Consistent with SD logic FP7, the dissemination of the role of marketing throughout the organization provides the ability of the firm to make an increased number of value propositions due to increased points of contact with the customer.

The marketing concept sanctioned a strong marketing function in the firm in order to inform the other business functions of customer needs (Webster 1992). RM distributes the role of marketing throughout the firm, thus shrinking the size of the function while the role of marketing expands throughout the firm. Gronroos (2004) goes so far as to suggest that a strong marketing department can actually be counterproductive to the development of a market orientation. The distribution of marketing across organizational functions provides the opportunity for an increased number of touch points to make an increased number of value propositions (FP7) with the customer. It also brings a greater number of network nodes into play which further increases the potential number and mix of resources that can be employed in coproduction.

As one example, supplier–manufacturer collaboration in product development has led to an entire research stream. As another example, the fast-moving consumer goods industry has seen the establishment of Customer Business Development (CBD) teams, multi-functional teams that have been organized around a customer to work with the customer to produce joint solutions to problems and joint value for both organizations. Some of these teams are even located near the customer premises. These can include members from sales, merchandising, logistics, manufacturing, finance, accounting, and human resources. Recognizing that within key accounts there are often separate buyers, payers, and users (Sheth and Mittal 2004), the selling organization needs to match their sales reps with the buyers, their finance and accounting with the payers, and their customer service with the users. The opportunity for value creation with the customer is distributed across the entire group that maintains the relationship with the customer. The CBD team interfaces with multiple entities at the customer, which is also multifunctional (in the Sheth and Mittal context, the buyers, payers and users). When these two groups interface, their intermingling goes well beyond a series of presentation of proposals from the CBD team, and rather focuses on joint value creation. The CBD team and the customer counterparts jointly team develop plans that deliver improved offerings to their common customer, the shopper/consumers in the store. By jointly developing plans, they are able to gain great efficiencies in terms of speed and cost, and deliver this savings to the consumer.

This view of the relationship with the customer is expressed in the following diagrams (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1995a). This has been labeled the “reverse bow-tie” model of B2B relationships. In Fig. 1, the traditional exchange relationship is shown as a bow-tie, where at the point of exchange, the seller and the buyer represent many other inputs, but the value of the exchange is created at a single point. In Fig. 2, the bow-tie is reversed, showing that there are multiple contacts between the manufacturer and the customer where value propositions can be offered, and where joint value can be created. Figure 3 then shows that this relationship does not exist for the sole purpose of the value to each other, but rather that the joint value is created for the customer’s customer. Figure 4 then recognizes that these relationships do not operate in a confined space, but rather exist in a larger network of interdependence.

This view of customer relationships shows where RM fits the S-D logic, and it also addresses the concern that Vargo (2009) expresses about the focus of RM on the dyad. Here the dyad is shown in the context with its greater network.

In the views provided above, RM reorients the positions of suppliers and customers through a business strategy of bringing them together in cooperative, trusting, and mutually beneficial relationships. These in turn are able to provide increased value propositions to their joint customers. The domain of RM seeks to provide the means and direction for organizations to create and manage an environment dedicated to mutual value creation.

RM Practices: CRM and CLV

The two previous sections have shown where the RM provides consistency with the S-D view through co-production of value with the customer (FP6), and organizing structures to allow new forms of value propositions (FP7). However, as Vargo (2009) shows, some of the key tools and measurements that have grown out of the relationship marketing perspective, notably CLV and CRM systems, are anchored in the G-D view, and have yet to transcend (or fit) into the S-D logic view. CRM and CLV are two of the dominant themes in the practice of RM. Other RM practices and measures include share of customer (or share of wallet), and the treatment of the customer as an asset, and these practices are, as Vargo suggests, rooted in the G-D view. Perhaps, however, depending on the way these measures and practices are deployed, that there are some consistencies with S-D logic. That is what we will examine in this section. We begin by describing CRM and CLV, and then examine a perspective that shows how these can transcend their traditional definitions and approaches and move into the S-D logic.

Customer relationship management (CRM) grew out of relationship marketing as an industry practice. There were two driving forces of this. The first was that firms had learned that existing customers generally had a greater ability to be more profitable than new customers, and thus a focus on customer retention of the more profitable customers became a company objective. Second, when working with key accounts, the organization has multiple contacts in the organization to match the multiple contact points of a single customer. As discussed in the previous section, within key accounts there are typically separate buyers, payers, and users (Sheth and Mittal 2004). While sales reps, finance/accounting, and customer service people are all likely to be in contact with the customer, few organizations are structured so that internally these groups talk with each other. From these two driving forces, organizations recognized that they needed to embed systems to share customer information across multiple functions in their organization. The systems that emerged were called customer relationship management, or “CRM,” and they were developed on basic database platforms that could hold all of the information about a customer in a central depository. Customer information could be accessed and updated by all individuals involved with the customer, which total enhanced the ability to effectively manage the relationship with the customer.

These applications have continued to develop and become central to the organization’s strategy. Many of these have been extended to operate remotely beyond the organization’s walls through internet access, and some are even shared with customers, allowing customer access. However, the objectives of CRM systems remain unchanged: maintain all information about a customer so that customers can be served according to their level of profitability, and allow all individuals in the organization who have contact with a customer to have access to complete customer information. In this view of CRM systems, customers are viewed from a G-D perspective.

Customer lifetime value (CLV) is also similar in a G-D perspective in that it creates a valuation of the customer to the firm. Typical CLV calculations take a rudimentary approach to calculating the value to the firm, and do not begin to examine value provided to the customer. It is one-way, and focuses on the dyad of the customer and the firm. At its most basic level, CLV generally requires three variables for its calculation. The first is the retention rate, or the expected time a customer will be with the firm. This estimate is based on history, and is typically presented as a percentage rate out of 100% that the customer will defect during the next subsequent time period (this varies based on the opportunity when a customer can leave the relationship). The second variable is the net marketing contribution of the customer. This is also estimated based on historical data, and includes the gross margin the customer will produce over the same time period used for the retention rate, less estimated marketing expenditures specifically spent towards retaining the customer. The third variable is the cost of capital, recognizing that calculating future value must be discounted to its current value. This is typically estimated on historical cost of capital, and the time period is the same as for the other two variables. These variables are placed in a relatively simple algebraic formula to calculate the expected CLV. If the cost of acquisition of a customer is known, then this is typically subtracted from the CLV amount.

CLV does not take into account a multitude of other potential value enhancers or detractors. A prominent omitted factor is word-of-mouth from the customer, which can add considerably to the customer’s value, or seriously decrease it if the customer is dissatisfied, or cannot make a strong recommendation. Since other customers are greatly impacted by current customers, this is a major limitation of CLV calculations. CLV also only examines the dyadic relationship, and does not consider the impact of the networks that surround the firms. For example, if the customer represents a strong identity, then anyone affected by this identity (supporters and detractors) can also have an impact on the firm. Finally, CLV doesn’t consider non-monetary costs and benefits, such as the resource commitment to manage the relationship or the knowledge and learning potential from the customer.

CRM and CLV: G-D or S-D Logic?

While the above discussion validates Vargo’s (2009) argument that RM practices are rooted in the G-D view, they can be viewed—at least to some degree—from the S-D logic side when considered in a broader context. The following is provided to suggest that these RM practices can fit in S-D logic.

-

1.

The focus on CRM is actually a prerequisite for the ability of the firm to engage in collaborative value-creation practices with customers. When a business understands that it may cost six to ten times more to acquire a customer that to retain a customer, the anonymous faceless customer base begins to become a well-defined and well-understood set of distinct customers, with whom relationships can be built and joint value can be created. At this point the firm can maintain a G-D approach, and use this information database to act on the customer, or it can use it to become more relational (FP8) and find more value propositions for the customer (FP7).

-

2.

CLV forms the rudimentary basis for valuation and determination of ongoing collaborative relationships. While CLV typically only considers an estimated retention rate, an estimated net marketing contribution, and the discount rate (time value of money), this can also serve as the starting point of more sophisticated key performance indicator (KPI) analysis of the firm to the customer. While initially one-way (seller to customer), this can evolve into a joint evaluation of the firm to the customer and the customer back to the selling firm. When this information is shared between both parties, it becomes the place where sources of joint value creation can be identified. For example, the consumer packaged goods industry has developed a joint scorecard where suppliers and retailers can score each other on a number of shared KPIs, then view the score from their respective partners. Moreover, because this data gets aggregated at an industry level, industry benchmarks can be provided to see how scores rank relative to industry averages (www.globalscorecard.net). The overall aggregated results of this data are regularly shared at an industry conference where the manufacturers and retailers can learn about best practices in collaboration. This broader view recognizes that in addition to the dyad, the relationship is part of a greater network, where there are a number of interdependencies.

-

3.

Using CRM and CLV to focus on profitable customers and to design partnering strategies to leverage customer resources, the efficiency and effectiveness of marketing efforts can be enhanced. When relationships are properly formed and managed, productivity is increased not only through lower search and transactions costs, but also through the new value that is created from integrating supplier and customer functions. An example of this was shown in the relationship between Eaton and Whirlpool. Such relationships and joint value creation do not spontaneously appear. They grow over time and have to be actively managed.

-

4.

CRM and CLV also provide the place for a firm to know which customers they should not invest time and resources, i.e., where co-produced value is likely to be minimal. Partnering with a customer to develop joint value can take considerable resources. Since resources of co-production of value are finite to both the firm and the customer, knowing which relationships to dissolve or at best treat at an arms-length transaction is beneficial. Even a rudimentary CLV calculation can help point the firm in the direction of customers where joint value creation may be more likely to be realized.

-

5.

In RM, a fundamental transformation in approach from traditional marketing occurs. The relationships shift from adversarial to cooperative, and the goals shift from market share to share of customers. The view of “share of customer,” or “share of wallet,” can be a G-D approach, where the firm is seen as having and keeping their hands in the customer’s pocket as long as possible. However, RM sees the key to attaining a higher share of each customer’s lifetime business is the systematic development and management of cooperative and collaborative partnerships. Cooperation and collaboration have to be managed and governed in some manner. RM views trust-based relational governance to be superior to contractual governance for cooperation and collaboration, and ultimately increased opportunities for co-produced value.

-

6.

The RM concepts of the treatment of the customer as an asset to be managed appears to be anchored in the G-D view, where the firm acts upon and manages the customer asset. As long as the focus is on the asset side of the balance sheet, then the G-D view would appear to prevail. However, an asset must be offset with either liabilities or equity on the balance sheet. In consumer goods, this termed brand equity, and in B2B this is termed relationship equity. Equity, by its nature, is valued by the market, not by the firm. This is consistent with the S-D view where value is defined by the customer. When RM takes the perspective that the equity represents the composite of the total consumer loyalty towards the brand, then in essence the value does not rest with the brand itself, but rather with the relationship that the consumer has with the brand. This latter view is in line with the S-D logic.

Even though some practices and tools of RM appear to be coming from the transaction-based G-D logic, the goal of these is to provide the ability for firms to manage in an ever more complex and information rich environment. RM practices such as CRM and CLV can be practiced in a dyadic fashion, from a G-D logic approach, and in many situations (probably most), that is the case. But the practice can also transcend the dyad and the view that the customer is to be acted upon. Practices such as CRM and measures such as CLV can provide a necessary basis for firms to select, deselect, and manage their resources towards joint value creation with the customer, rather than simply marketing an offering to the customer.

Conclusion

This article has shown that RM offers two views of the customer, one that is anchored in the S-D logic, and another one that is anchored in the G-D. Studying the history of relationship marketing shows that these represent dual paths in the development of research and practice in relationship marketing. Understanding these dual paths helps sort through the issues posed by Vargo (2009) as to the extent that RM is compatible with the S-D view. The answer proposed in this article is that for one path, where the customer is seen as co-producer of value, the answer is yes, they are compatible. For the other path, it appears anchored in the G-D view. However, seen in the light as facilitators of larger processes, tools and measures such as CRM, CLV, share of wallet, and the asset view of the customer of RM can be viewed in a larger context that transcends its traditional understanding and is part of a higher-order SD conceptualization.

References

Berry, L. (1983). Relationship marketing. In L. L. Berry, G. L. Shostack, & G. D. Upah (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on services marketing (pp. 25–26). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Dwyer, R. F., Schurr, P., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(April), 11–27.

Gruen, T. W. (1997). Relationship marketing: The route to marketing efficiency and effectiveness. Business Horizons, November-December, 32–38.

Gruen, T. W., Osmonbekov, T., & Czaplewski A.(2006). eWOM: The impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 59(4), 449–456.

Gronroos, C. (2004). The relationship marketing process: Communication, interaction, dialogue, value. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 19(2), 99–113.

Gummesson, E. (1987). The new marketing—Developing long-term interactive relationships. Long Range Planning, 20(4), 10–20.

Gummesson, E. (1996). Relationship marketing: The emperor’s new clothes or paradigm shift? Research methodologies for ‘The New Marketing’ (pp. 3–19). Latimer: ESOMAR/EMAC.

Gwinner, K., Gremler, D., & Bitner, M. J. (1998). Relational benefits in services industries: The customer’s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 101–114.

Kotler, P. (2003). A Framework for Marketing Management. New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.

Morgan, R., & Hunt, S. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, July, 20–38.

Normann, R., & Ramirez, R. (1993). From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. Harvard Business Review, July–August, 65–77.

Petrof, J. (1997). Relationship marketing: The wheel reinvented? Business Horizons, November–December, 25–31.

Rackham, N., Friedman, L., & Ruff, R. (1995). Getting Partnering Right. Columbus: McGraw-Hill.

Sheth, J., & Parvatiyar, A. (1995a). The evolution of relationship marketing. International Business Review, 4(4), 397–418.

Sheth, J., & Parvatiyar, A. (1995b). Relationship marketing in consumer markets: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 255–271.

Sheth, J., & Mittal, B. (2004). Consumer behavior: A managerial perspective. Thompson: Southwestern Press.

Thorelli, H. B. (1986). Networks: Between markets and hierarchies. Strategic Management Journal, 7(1), 37–51.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(January), 1–17.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch R. F. (2008). Service dominant logic: Continuing the evolutions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(Spring), 1–10.

Vargo, S. L. (2009). Toward a transcending conceptualization of relationship: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 24(5/6), 373–379.

Webster, F. E. Jr. (1992). The changing role of marketing in the corporation. Journal of Marketing, October, 1–17.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gruen, T.W., Hofstetter, J.S. The Relationship Marketing View of the Customer and the Service Dominant Logic Perspective. J Bus Mark Manag 4, 231–245 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12087-010-0043-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12087-010-0043-3