Abstract

Within the last decade, non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity (NCGS) has been increasingly discussed not only in the media but also among medical specialties. The existence and the possible triggers of NCGS are controversial. Three international expert meetings which proposed recommendations for NCGS were not independently organized and only partially transparent regarding potential conflicts of interest of the participants. The present position statement reflects the following aspects about NCGS from an allergist’s and nutritionist’s point of view: (A) Validated diagnostic criteria and/or reliable biomarkers are still required. Currently, this condition is frequently self-diagnosed, of unknown prevalence and non-validated etiology. (B) Gluten has not been reliably identified as an elicitor of NCGS because of high nocebo and placebo effects. Double-blind, placebo-controlled provocation tests are of limited value for the diagnosis of NCGS and should be performed in a modified manner (changed relation of placebo and active substance). (C) Several confounders hamper the assessment of subjective symptoms during gluten-reduced or gluten-free diets. Depending on the selection of food items, e.g., an increased vegetable intake with soluble fibers, diets may induce physiological digestive effects and can modify gastrointestinal transit times independent from the avoidance of gluten. (D) A gluten-free diet is mandatory in celiac disease based on scientific evidence. However, a medically unjustified avoidance of gluten may bear potential disadvantages and risks. (E) Due to a lack of diagnostic criteria, a thorough differential diagnostic work-up is recommended when NCGS is suspected. This includes a careful patient history together with a food-intake and symptom diary, if necessary an allergy diagnostic workup and a reliable exclusion of celiac disease. We recommend such a structured procedure since a medically proven diagnosis is required before considering the avoidance of gluten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) or non-celiac wheat sensitivity is an increasingly discussed disorder. The mechanism is unknown and reliable biomarkers for diagnosis are lacking. Whether it is a specific disease entity and which wheat component is the responsible trigger is a long-running controversy [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Reported symptoms may be caused by undiagnosed celiac disease, variants of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or other undiagnosed functional disorders of the gut [7, 8]. Thus, individuals reporting gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms after wheat consumption may be wrongly characterized with NCGS. Three international expert meetings concerning NCGS have taken place [9,10,11]. Those meetings were not organized independent of “interested parties” and findings did not convincingly exclude possible conflict of interest of the participants and/or sponsors. From an allergist’s point of view, the diagnostic algorithm proposed during the third expert meeting is inappropriate for the diagnosis of NCGS [11]. The following issues will be discussed:

-

1.

Absence of validated diagnostic criteria and/or suitable biomarkers, frequent self-diagnosis, undocumented prevalence and unconfirmed etiology of reported symptoms.

-

2.

No reliable identification of gluten as trigger of NCGS during controlled food challenges due to an a priori bias of the subject toward experiencing symptoms.

-

3.

Several variables confounding the evaluation of subjective symptoms during gluten-reduced and/or -free diet.

-

4.

Potential disadvantages and risks will prevail in case of medically unjustified gluten avoidance.

-

5.

Proposed diagnostic procedure in suspected NCGS.

Issue 1

Absence of validated diagnostic criteria and/or suitable biomarkers, frequent self-diagnosis, undocumented prevalence and unconfirmed etiology of reported symptoms. As validated diagnostic criteria are lacking to date, the prevalence of NCGS cannot be assessed. Recent survey results are based primarily on self-diagnosis and reveal how many people think that they are affected rather than proving actual prevalence [12,13,14]. Moreover, the exclusion of other diseases such as IBS, celiac disease or functional GI disorders has not been systematically evaluated in published surveys and studies [4, 7, 8, 15,16,17]. Without an appropriate differential diagnosis these data should be interpreted with caution [18]. A recent study in individuals reporting wheat sensitivity suggests a compromised intestinal epithelial barrier as cause for a systemic immune activation [19]. The identification of possible triggers was not the aim of the study. The authors consider their findings only as a basis for further research.

Issue 2

No reliable identification of gluten as trigger of NCGS during controlled food challenges due and an a priori bias of the subject toward experiencing symptoms. Results from various studies with food challenges of classical double-blind, placebo-controlled (DBPCFC) design reveal that only a minority of individuals suspected of suffering from NCGS are able to correctly identify gluten as trigger [20,21,22,23]. It cannot be excluded that positive test results are triggered by the expectation of symptoms rather than gluten as a true elicitor [5, 20,21,22]. This postulate is supported by the observation that most patients react comparably to actual gluten and placebo [20,21,22]. In order to mitigate the expectations of a patient, the number of placebo challenges can be increased [24, 25]. Such an approach may identify true gluten responders better than the proposed recommendation to increase the number of gluten challenges [11]. We recommend a ratio of placebo to active of at least 2:1 in controlled challenges. This approach has been successfully utilized in a current study, determining that the majority of patients with suspected NCGS cannot identify gluten as trigger of their symptoms [26].

Issue 3

Several variables confounding the evaluation of subjective symptoms during gluten-reduced and/or -free diet. A gluten-reduced diet can, according to food selection (i. e., if rich in vegetables with soluble fiber), induce physiological digestive effects and alter intestinal transit time independently of gluten content. Therefore, certain food components such as soluble fiber are supposed to elicit a therapeutic effect. Hence, patients may benefit from a gluten-free diet by changing food composition and thereby inducing physiological digestive effects and, thus, altering intestinal transit time physiologically rather than by eliminating gluten [21]. A temporary gluten reduction, but not total gluten avoidance is recommended in the German IBS guideline [27]. As mentioned therein, IBS-afflicted individuals can benefit from a change of fiber quality. Optimal benefit can be achieved if soluble fiber, such as those in psyllium husks and certain vegetables, are increased in parallel to a reduction of cereal fiber [27]. Thus, IBS patients will benefit from their food selection in favor of soluble fiber but not from gluten avoidance. This view is supported by the observation made in several studies that many individuals benefit from a diet free from gluten while only a minority identified gluten in a DBPCFC [6, 20,21,22,23, 26]. Apart from gluten, many other potential triggers are discussed, such as fructans, amylase-trypsin inhibitors (ATIs), etc. [3, 4, 28].

Issue 4

Potential disadvantages and risks will prevail in case of medically unjustified gluten avoidance. A strict gluten-free diet is mandatory in confirmed celiac disease. In contrast, potential disadvantages and risks exist in the case of self-diagnosis without professional dietetic support [27, 29, 30]. Risks of gluten-free diet without a medically proven indication are as follows:

-

triggering of an eating disorder, such as Orthorexia nervosa [15],

-

eliciting or worsening of constipation, potentially causing rectal diseases [31, 32], and

-

increased risk of dyslipidemia [33].

Furthermore, there are known disadvantages of a gluten-free diet regarding

Therefore, a recommendation for a temporarily limited gluten reduction (as mentioned in the German IBS guideline) is reasonable. In contrast, a recommendation for a gluten-free diet without medically proven diagnosis (celiac disease) is not currently warranted.

Issue 5

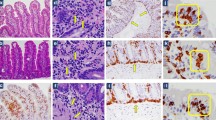

Proposed diagnostic procedure in suspected NCGS. Lacking viable criteria, a proven diagnosis of NCGS is not possible. A thorough differential diagnostic work-up is mandatory (Fig. 1), which includes the following: a comprehensive and interdisciplinary patient history in combination with the evaluation of a food intake/symptom diary; if justified an allergy work-up; and a definitive exclusion of celiac disease—to be meaningful, gluten must be part of the diet for at least three months in sufficiently high amounts (15–20 g gluten per day, equaling 4–5 slices of bread).

Conclusion

Without a confirmed diagnosis, a gluten-free diet is unjustified and not recommended. Patients who intend to continue to restrict their diet despite the recommendation should be encouraged to seek professional nutritional counselling.

Abbreviations

- ATI:

-

Amylase-trypsin inhibitors

- DBPCFC:

-

Double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge

- DGAKI:

-

German Society of Allergology and Clinical Immunology

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- NCGS:

-

Non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity

References

Makharia A, Catassi C, Makharia GK. The overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a clinical dilemma. Nutrients. 2015;7:10417–26.

Kabbani TA, Vanga RR, Leffler DA, Villafuerte-Galvez J, Pallav K, Hansen J, et al. Celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity? An approach to clinical differential diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:741–6. quiz 747.

Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1195–204.

Gibson PR, Skodje GI, Lundin KEA. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:86–9.

Molina-Infante J, Carroccio A. Suspected nonceliac gluten sensitivity confirmed in few patients after gluten challenge in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:339–48.

Lebwohl B, Leffler DA. Exploring the strange new world of non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1613–5.

Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, Farmer AD, Fukudo S, Mayer EA, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16014.

Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1257–61.

Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, Dolinsek J, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012;10:13.

Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Calabro A, Carroccio A, et al. Non-Celiac Gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5:3839–53.

Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Carroccio A, Castillejo G, et al. Diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS): the Salerno experts’ criteria. Nutrients. 2015;7:4966–77.

van Gils T, Nijeboer P, IJssennagger CE, Sanders DS, Mulder CJ, Bouma G. Prevalence and characterization of self-reported gluten sensitivity in the Netherlands. Nutrients. 2016;8:E714.

Aziz I, Lewis NR, Hadjivassiliou M, Winfield SN, Rugg N, Kelsall A, et al. A UK study assessing the population prevalence of self-reported gluten sensitivity and referral characteristics to secondary care. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:33–9.

Lis DM, Stellingwerff T, Shing CM, Ahuja KD, Fell JW. Exploring the popularity, experiences, and beliefs surrounding gluten-free diets in nonceliac athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2015;25:37–45.

Marild K, Stordal K, Bulik CM, Rewers M, Ekbom A, Liu E, et al. Celiac disease and anorexia nervosa: a nationwide study. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20164367.

Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Characterization of adults with a self-diagnosis of nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:504–9.

Biesiekierski JR, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Is gluten a cause of gastrointestinal symptoms in people without celiac disease? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:631–8.

Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, Biagi F, Fasano A, Green PH, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62:43–52.

Uhde M, Ajamian M, Caio G, De Giorgio R, Indart A, Green PH, et al. Intestinal cell damage and systemic immune activation in individuals reporting sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease. Gut. 2016;65:1930–7.

Zanini B, Basche R, Ferraresi A, Ricci C, Lanzarotto F, Marullo M, et al. Randomised clinical study: gluten challenge induces symptom recurrence in only a minority of patients who meet clinical criteria for non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:968–76.

Di Sabatino A, Volta U, Salvatore C, Biancheri P, Caio G, De Giorgio R, et al. Small amounts of gluten in subjects with suspected nonceliac gluten sensitivity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1604–1612.e3.

Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, Rosella O, Muir JG, Gibson PR. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:320–328.e1–3.

Elli L, Tomba C, Branchi F, Roncoroni L, Lombardo V, Bardella MT, et al. Evidence for the presence of non-celiac gluten sensitivity in patients with functional gastrointestinal symptoms: results from a multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge. Nutrients. 2016;8:84.

Dölle S, Grünhagen J, Worm M. Dem Täter auf der Spur: Indikation und praktische Umsetzung von Nahrungsmittelprovokationen im Erwachsenenalter. Allergologie. 2016;39:523–32.

Niggemann B, Beyer K, Erdmann S, Fuchs T, Kleine-Tebbe J, Lepp U, et al. Standardisierung von oralen Provokationstests bei Verdacht auf Nahrungsmittelallergie. Allergo J. 2011;20:149–60.

Dale HF, Hatlebakk JG, Hovdenak N, Ystad SO, Lied GA. The effect of a controlled gluten challenge in a group of patients with suspected non-coeliac gluten sensitivity: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled challenge. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13332.

Layer P, Andresen V, Pehl C, Allescher H, Bischoff SC, Claßen M, et al. S3-Leitlinie Reizdarmsyndrom: Definition, Pathophysiologie, Diagnostik und Therapie. Gemeinsame Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neurogastroenterologie und Motilität (DGNM). Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:237–93.

Skodje GI, Sarna VK, Minelle IH, Rolfsen KL, Muir JG, Gibson PR, et al. Fructan, rather than gluten, induces symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:529–539.e2.

Lebwohl B, Cao Y, Zong G, Hu FB, Green PHR, Neugut AI, et al. Long term gluten consumption in adults without celiac disease and risk of coronary heart disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j1892.

Fry L, Madden AM, Fallaize R. An investigation into the nutritional composition and cost of gluten-free versus regular food products in the UK. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31:108–20.

Andresen V, Enck P, Frieling T, Herold A, Ilgenstein P, Jesse N, et al. S2k guideline for chronic constipation: definition, pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy. Z Gastroenterol. 2013;51:651–72.

Muller-Lissner S, Tack J, Feng Y, Schenck F, Specht Gryp R. Levels of satisfaction with current chronic constipation treatment options in Europe—an internet survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:137–45.

Welstead L. The gluten-free diet in the 3rd millennium: rules, risks and opportunities. Diseases. 2015;3:136–49.

Shah S, Akbari M, Vanga R, Kelly CP, Hansen J, Theethira T, et al. Patient perception of treatment burden is high in celiac disease compared with other common conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1304–11.

Pfeiffer K, Kohlenberg-Müller K. Was kostet eine glutenfreie Ernährung bei Zöliakie? Verzehrserhebungen und Selbsteinschätzungen zum diätetisch bedingten Aufwand. Aktuel Ernahrungsmed. 2015;40:P1_6.

Bulka CM, Davis MA, Karagas MR, Ahsan H, Argos M. The unintended consequences of a gluten-free diet. Epidemiology. 2017;28:e24–e5.

Raehsler SL, Choung RS, Marietta EV, Murray JA. Accumulation of Heavy Metals in People on a Gluten-Free Diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:244–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank Steve Love, PhD, Laguna Niguel, CA, USA, for reading the manuscript, helpful suggestions, and editorial assistance with the English translation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Reese, I., Schäfer, C., Kleine-Tebbe, J. et al. Non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity (NCGS)—a currently undefined disorder without validated diagnostic criteria and of unknown prevalence. Allergo J Int 27, 147–151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-018-0070-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-018-0070-2