Abstract

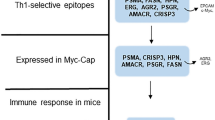

The ability of two plasmid DNA vaccines to stimulate lymphocytes from normal human donors and to generate antigen-specific responses is demonstrated. The first vaccine (truncated; tPSMA) encodes for only the extracellular domain of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). The product, expressed following transfection with this vector, is retained in the cytosol and degraded by the proteasomes. For the “secreted” (sPMSA) vaccine, a signal peptide sequence is added to the expression cassette and the expressed protein is glycosylated and directed to the secretory pathway. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DCs) are transiently transfected with either sPSMA or tPSMA plasmids. The DCs are then used to activate autologous lymphocytes in an in vitro model of DNA vaccination. Lymphocytes are boosted following priming with transfected DCs or with peptide-pulsed monocytes. Their reactivity is tested against tumor cells or peptide-pulsed T2 target cells. Both tPSMA DCs and sPSMA DCs generate antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses. The immune response is restricted toward one of the four PSMA-derived epitopes when priming and boosting is performed with sPSMA. In contrast, tPSMA-transfected DCs prime T cells toward several PSMA-derived epitopes. Subsequent repeated boosting with transfected DCs, however, restricts the immune response to a single epitope due to immunodominance.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mincheff M, Tchakarov S, Zoubak S, et al. Naked DNA and adenoviral immunizations for immunotherapy of prostate cancer: a phase I/II clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2000;38:208–217.

Mincheff M, Altankova I, Zoubak S et al. In vivo transfection and/or cross-priming of dendritic cells following DNA and adenoviral immunizations for immunotherapy of cancer—changes in peripheral mononuclear subsets and intracellular IL-4 and IFN-gamma lymphokine profile. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;39:125–132.

Weber LW, Bowne WB, Wolchok JD, et al. Tumor immunity and autoimmunity induced by immunization with homologous DNA. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1258–1264.

Israeli RS, Powell CT, Fair WR, et al. Molecular cloning of a complementary DNA encoding a prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 1993;53:227–230.

Wright GL Jr, Grob BM, Haley C, et al. Upregulation of prostate-specific membrane antigen after androgen-deprivation therapy. Urology. 1996;48:326–334.

Chang SS, Gaudin PB, Reuter VE, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen: present and future applications. Urology 2000;55:622–629.

Chang SS, Gaudin PB, Reuter VE, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen: much more than a prostate cancer marker. Mol Urol. 1999;3:313–320.

Heston WD . [Significance of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). A neurocarboxypeptidase and membrane folate hydrolase]. Urologe A. 1996;35:400–407.

Silver DA, Pellicer I, Fair WR, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:81–85.

Shneider BL, Thevananther S, Moyer MS, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel peptidase from rat and human ileum. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31006–31015.

Halsted CH, Ling E, Luthi-Carter R, et al. Folylpoly-gamma-glutamate carboxypeptidase from pig jejunum. Molecular characterization and relation to glutamate carboxypeptidase II. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30746.

Chang SS, O'Keefe DS, Bacich DJ, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is produced in tumor-associated neovasculature. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2674–2681.

Sprent J, Schaefer M . Antigen-presenting cells for unprimed T cells. Immunol Today. 1989;10:17–23.

Bennink JR, Anderson R, Bacik I, et al. Antigen processing: where tumor-specific T-cell responses begin. J Immunother. 1993;14:202–208.

Restifo NP, Kawakami Y, Marincola F, et al. Molecular mechanisms used by tumors to escape immune recognition: immunogenetherapy and the cell biology of major histocompatibility complex class I. J Immunother. 1993;14:182–190.

Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998.

Schreiber H, Wu TH, Nachman J, et al. Immunodominance and tumor escape. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:25–31.

Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD . The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:95–109.

Yewdell JW, Bennink JR . Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:51–88.

Pinto JT, Suffoletto BP, Berzin TM, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen: a novel folate hydrolase in human prostatic carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1445–1451.

Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ . Structure of membrane glutamate carboxypeptidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1339:247–252.

Holmes EH, Greene TG, Tino WT, et al. Analysis of glycosylation of prostate-specific membrane antigen derived from LNCaP cells, prostatic carcinoma tumors, and serum from prostate cancer patients. Prostate Suppl. 1996;7:25–29.

Barinka C, Rinnova M, Sacha P, et al. Substrate specificity, inhibition and enzymological analysis of recombinant human glutamate carboxypeptidase II. J Neurochem. 2002;80:477–487.

DeMars R, Chang CC, Shaw S, et al. Homozygous deletions that simultaneously eliminate expressions of class I and class II antigens of EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cells. I. Reduced proliferative responses of autologous and allogeneic T cells to mutant cells that have decreased expression of class II antigens. Hum Immunol. 1984;11:77–97.

Matzinger P . The JAM test. A simple assay for DNA fragmentation and cell death. J Immunol Methods. 1991;145:185–192.

Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Hull LK, et al. Sequence motifs important for peptide binding to the human MHC class I molecule, HLA-A2. J Immunol. 1992;149:3580–3587.

Kaye PM . Costimulation and the regulation of antimicrobial immunity. Immunol Today. 1995;16:423–427.

Lenschow DJ, Walunas TL, Bluestone JA . CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:233–258.

Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, et al. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413.

Manzotti CN, Tipping H, Perry LC, et al. Inhibition of human T cell proliferation by CTLA-4 utilizes CD80 and requires CD25+ regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2888–2896.

Davis MM, Chien YH, Bjorkman PJ, et al. A possible basis for major histocompatibility complex-restricted T-cell recognition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 1989;323:521–524.

Kedl RM, Schaefer BC, Kappler JW, et al. T cells down-modulate peptide-MHC complexes on APCs in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:27–32.

Mitchison NA . Specialization, tolerance, memory, competition, latency, and strife among T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:1–12.

Lightstone E, Marvel J, Mitchison A . Memory in helper T cells of minor histocompatibility antigens, revealed in vivo by alloimmunizations in combination with Thy-1 antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:115–122.

Clark EA, Lake P, Favila-Castillo L . Modulation of Thy-1 alloantibody responses: donor cell-associated H-2 inhibition and augmentation without recipient Ir gene control. J Immunol. 1981;127:2135–2140.

Rapoport TA, Rolls MM, Jungnickel B . Approaching the mechanism of protein transport across the ER membrane. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:499–504.

Kedl RM, Rees WA, Hildeman DA, et al. T cells compete for access to antigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1105–1113.

Greene JL, Leytze GM, Emswiler J, et al. Covalent dimerization of CD28/CTLA-4 and oligomerization of CD80/CD86 regulate T cell costimulatory interactions. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26762–26771.

van der Merwe PA, Bodian DL, Daenke S, et al. CD80 (B7-1) binds both CD28 and CTLA-4 with a low affinity and very fast kinetics. J Exp Med. 1997;185:393–403.

Thompson CB, Allison JP . The emerging role of CTLA-4 as an immune attenuator. Immunity. 1997;7:445–450.

Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270:985–988.

Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–547.

Egen JG, Allison JP . Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 accumulation in the immunological synapse is regulated by TCR signal strength. Immunity. 2002;16:23–35.

Masteller EL, Chuang E, Mullen AC, et al. Structural analysis of CTLA-4 function in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:5319–5327.

Doyle AM, Mullen AC, Villarino AV, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) restricts clonal expansion of helper T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:893–902.

Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F . Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302.

Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–310.

Shevach EM . Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:423–449.

Groux H, Powrie F . Regulatory T cells and inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Today. 1999;20:442–445.

Sakaguchi S . Regulatory T cells: mediating compromises between host and parasite. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:10–11.

Smith SG, Patel PM, Porte J, et al. Human dendritic cells genetically engineered to express a melanoma polyepitope DNA vaccine induce multiple cytotoxic T-cell responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4253–4261.

Mateo L, Gardner J, Chen Q, et al. An HLA-A2 polyepitope vaccine for melanoma immunotherapy. J Immunol. 1999;163:4058–4063.

Firat H, Garcia-Pons F, Tourdot S, et al. H-2 class I knockout HLA-A2.1-transgenic mice: a versatile animal model for preclinical evaluation of antitumor immunotherapeutic strategies. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3112–3121.

Loirat D, Lemonnier FA, Michel ML . Multiepitopic HLA-A*0201-restricted immune response against hepatitis B surface antigen after DNA-based immunization. J Immunol. 2000;165:4748–4755.

Palmowski MJ, Choi EM, Hermans IF, et al. Competition between CTL narrows the immune response induced by prime-boost vaccination protocols. J Immunol. 2002;168:4391–4398.

Kedl RM, Kappler JW, Marrack P . Epitope dominance, competition and T cell affinity maturation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:120–127.

Lu J, Celis E . Recognition of prostate tumor cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5807–5812.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grant N00014-00-1-0787 from the Office of Naval Research and by award No. DAMD17-02-1-0239. The US Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick, MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office. The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. For the purpose of this article, information includes news releases, articles, manuscripts, brochures, advertisements, still and motion pictures, speeches, trade association proceedings, etc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mincheff, M., Zoubak, S., Altankova, I. et al. Human dendritic cells genetically engineered to express cytosolically retained fragment of prostate-specific membrane antigen prime cytotoxic T-cell responses to multiple epitopes. Cancer Gene Ther 10, 907–917 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cgt.7700647

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cgt.7700647

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Processing of Tumor Antigen Differentially Impacts the Development of Helper and Effector CD4+ T-cell Responses

Molecular Therapy (2010)

-

Immune responses against PSMA after gene-based vaccination for immunotherapy – A: results from immunizations in animals

Cancer Gene Therapy (2006)

-

Depletion of CD25+ cells from human T-cell enriched fraction eliminates immunodominance during priming with dendritic cells genetically modified to express a secreted protein

Cancer Gene Therapy (2005)