Abstract

This study proposes and tests a model of the relations among corporate accountants’ perceptions of the ethical climate in their organization, the perceived importance of corporate ethics and social responsibility, and earnings management decisions. Based on a field survey of professional accountants employed by private industry in Hong Kong, we found that perceptions of the organizational ethical climate were significantly associated with belief in the importance of corporate ethics and responsibility. Belief in the importance of ethics and social responsibility was also significantly associated with accountants’ ethical judgments and behavioral intentions regarding accounting and operating earnings manipulation. These findings suggest that perceptions of ethical climate, usually presumed to reflect the “tone at the top” in the organization, lead accounting professionals to rationalize earnings management decisions by adjusting their attitudes toward the importance of corporate ethics and social responsibility. This is the first study to document a relationship between organizational ethical climate and professional accountants’ support for corporate ethics and social responsibility, and also the first study to document that industry accountants’ views toward corporate ethics and social responsibility are associated with their willingness to manipulate earnings. The findings have important implications, suggesting that organizational efforts to enhance the ethical climate and emphasize the importance of corporate ethics and social responsibility could reduce the prevalence of earnings manipulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Archival studies have addressed the relationships between certain aspects of organizational governance and earnings management. For instance, Klein (2002) found that abnormal accounting accruals (a measure of earnings management) were significantly higher when either the audit committee or the board of directors lacked independence. Xie et al. (2003) found that when members of corporate boards of directors and audit committees had more extensive corporate or financial backgrounds (a measure of financial sophistication), companies were less likely to engage in earnings management. Earnings management was also less likely to occur when boards or audit committees met more frequently. García‐Meca and Sánchez‐Ballesta (2009) concluded based on a meta-analysis of 35 studies that when audit committees and boards of directors are more independent, earnings management is less likely to occur. Such studies provide support for the general contention that the tone at the top in an organization may influence earnings management.

Victor and Cullen (1987, 1988) assumed that, although individual differences in climate perceptions will exist, in a given organization there will be one or more dominant ethical climate dimensions. Most studies of organizational ethical culture/climate fall into one of two categories: (1) studies that focus on one or a few organizations and attempt to identify dominant or influential climate dimensions within these organizations (e.g., Victor and Cullen 1988); and (2) studies that survey employees from many organizations in an attempt to identify relationships between ethical climate perceptions and other variables of interest (e.g., Treviño et al. 1998). Studies of the first type allow for comparisons of the dominant climate dimensions across different types of organizations or organizational subunits. Studies that are based on surveys of employees from a relatively large number of organizations (including the current study) do not allow for the categorization of organizations or organizational subunits according to their climate dimensions, but provide a basis for identifying relationships between climate perceptions and other variables that are generalizable across multiple organizations.

Note that these five climate dimensions were also the ones identified in Victor and Cullen (1988).

We also feel that these three climate types are the most relevant to the ethical decisions of professional accountants, including the types of earnings management decisions tested in our study. Such decisions involve the fundamental tension that accountants often face between upholding laws and professional standards (principled/cosmopolitan) and serving the public interest (benevolent/cosmopolitan), or succumbing to temptations to acquiesce in earnings manipulations to enhance company profits and/or promote one’s personal career (instrumental). The other commonly identified ethical climate types appear somewhat less relevant to such decisions. For example, the caring climate discussed by Martin and Cullen (2006) combines elements of the benevolent/individual (friendship) and benevolent/local (team interests) climate types, which are clearly less relevant to ethical decisions in accounting than the benevolent/cosmopolitan (public interest) climate. Each of the three principled climates (individual, local, and cosmopolitan) has also commonly emerged in prior studies (Martin and Cullen 2006). But again, among these three we feel that the principled/cosmopolitan climate focused on in our study is the most relevant to earnings management decisions. The principled/cosmopolitan climate emphasizes following laws (e.g., securities laws relating to financial reporting) and professional codes of conduct, both highly relevant to professional accountants’ decisions. We acknowledge that principled/local climates (e.g., following organizational codes of ethics) are also relevant to such decisions, but for professionals laws and professional codes of conduct take precedence over organizational rules. The principled/individual climate (following one’s own personal principles of morality) may obviously influence ethical decisions, but in professional work environments such personal principles should be subordinated to laws and professional codes.

Lämsä et al. (2008) argue that the three primary sources of socialization are education, peer groups, and organizational work settings. Due to the business focus of PRESOR attitudes, we feel that the two most influential sources of socialization or learning processes are likely to be formal education (particularly business education) and work settings.

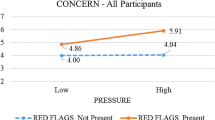

The questionnaire items that measure support for the stockholder view dimension are reverse-scored; consequently, in Fig. 3 higher scores for both the stockholder view and stakeholder view dimensions of the PRESOR scale represent stronger belief in the importance of corporate ethics and social responsibility.

Since most ethical climate studies, including some accounting studies, have found an instrumental climate dimension that combines elements of the egoistic/individual and egoistical/local climates (Martin and Cullen 2006), we are proposing one hypothesis that includes both these climate dimensions.

Following the early results of Singhapakdi et al. (1996), Elias (2002) grouped the PRESOR items into three factors: (1) social responsibility; (2) long-term gains; and (3) short-term gains. The social responsibility and long-term gains factors roughly correspond with our measure of the stakeholder view, while the short-term gains factor corresponds with our stockholder view. Elias’ (2002) results for the sample of public accountants indicated that five of six possible relationships between the three PRESOR factors and earnings manipulations (operating and accounting) were significant at conventional levels. The only relationship that was not significant was that between long-term gains and operating manipulations.

As recognized in the influential Hunt–Vitell theory of ethical decision making in organizations (Hunt and Vitell 1986, 1991), decision makers make both deontological (based on moral principles) and teleological (based on practical consequences) ethical evaluations of issues, both of which should directly affect overall ethical judgments of an issue, which in turn affect behavioral intentions. However, the Hunt–Vitell model also posits that practical or teleological evaluations of ethical issues (in contrast to deontological evaluations) have additional direct effects on behavioral intentions. Thus, ethical evaluations that are highly dependent on practical or teleological considerations should have relatively large impacts on behavioral intentions.

Note that we are not proposing separate hypotheses for the associations between PRESOR attitudes and operating versus accounting manipulations, because we do not expect these relationships to differ across manipulation types. Accountants’ attitudes toward the importance of corporate ethics and social responsibility should exhibit the same basic relationships with ethical decision making, regardless of the specific types of ethical transgressions involved. This argument is supported by the findings of Elias (2002), who documented that PRESOR attitudes were associated with ethical judgments for both operating and accounting manipulations. Indeed, because PRESOR attitudes are not specific to any particular business discipline, they have the potential to influence ethical decision making across a wide variety of business situations (Singhapakdi et al. 1996).

As indicated by our research hypotheses and Fig. 3, we are proposing that the two PRESOR dimensions will fully mediate the relationship between ethical climate and ethical decisions (we have not hypothesized any direct paths from ethical climate to ethical judgments or behavioral intentions). This is because (1) relatively little evidence exists on the direct relationships between ethical climate/culture and ethical decision making in accounting; and (2) the existing evidence does not provide robust or consistent support for the existence of such relationships. For example, Shafer (2008) found that only one of twelve possible direct relationships between ethical climate and ethical judgments was significant. Three of four relationships between ethical climate and behavioral intentions were significant (p < .05), but these results only held true for high relativists. In addition, Shafer and Wang (2011) found that only one of ten potential direct associations between their ethical climate/culture measures and ethical judgments was significant. Also note that we are proposing that the relationships among the PRESOR dimensions and behavioral intentions will be partially mediated by ethical judgments (we have proposed both direct links from the PRESOR dimensions to behavioral intentions and indirect links through ethical judgments). The validity of these assumptions is later addressed by testing alternative model specifications.

It is relatively common in the accounting ethics literature to measure behavioral intentions by asking participants to estimate the likelihood that (1) they themselves, and (2) their peers or professional colleagues would engage in similar actions (e.g., Shafer 2008).

Though it would have been desirable to have a larger sample size, we feel that the sample size is reasonable based on common recommendations for SEM modeling and prior practice in accounting. Smith and Langfield-Smith (2004, p. 66) note that there is variation in recommended minimum sample sizes in the SEM literature, with some authors suggesting a minimum of 100 participants and others a minimum of 200. Thus, our sample size exceeds the larger of these recommendations. Smith and Langfield-Smith (2004) also noted that among the 20 studies they reviewed that used SEM in management accounting contexts, 11 had sample sizes below 200, and three had samples smaller than 100 participants.

We asked participants to indicate their total number of years of “professional accounting experience,” based on the expectation that this term is commonly understood to include both public accounting experience and experience in accounting positions in other types of organizations such as government and industry.

We were informed by accounting personnel in private industry in Hong Kong that the term “general staff” would be commonly understood as relatively low-level positions in an accounting department, while the terms “senior staff”, “supervisor,” and “manager” would be understood to be progressively higher position levels. This information is supported by our data. The mean total professional experience reported by general staff, senior staff, supervisors, and managers was 5, 9, 11, and 15 years, respectively. The mean level of experience with their current employer reported by these respective groups was 2, 4, 5, and 6 years.

We also conducted tests of the relations between the continuous variables in our conceptual model and the demographic measures. These tests revealed relatively few significant relationships. Age, total professional experience, and experience with the current employer had little influence on the continuous measures. The only exceptions were that age was correlated (p < .05) with ethical judgments and intentions for operating manipulations, and total professional experience was also correlated (p < .05) with ethical judgments for operating manipulations. Older participants tended to judge operating manipulations more leniently, and older participants and those with more total professional experience indicated a higher likelihood of engaging in such manipulations. Gender was significantly correlated with behavioral intentions for operating manipulations (p = .01) and with the stakeholder view (p = .003). Relative to males, females were less likely to express an intention to engage in operating manipulations, and more likely to support the stakeholder view. Position had a highly significant effect (p < .0001) on behavioral intentions for operating manipulations, with employees in higher positions estimating higher likelihoods of committing such actions. Supervisors and managers also believed less strongly in the stakeholder view (p = .046).

We initially analyzed the data using exploratory (rather than confirmatory) factor analysis because (1) significant variations in factor loadings for some of the instruments, in particular the ethical climate and PRESOR scales, have been found in previous studies; and (2) the instruments have had only very limited prior usage among Chinese management accountants; thus, it should not be assumed that their factor structure will be the same as that previously documented in other professional and national contexts.

Responses to both the operating and accounting scenarios factor analyzed the same regardless of whether the items for the two related cases were analyzed individually or were averaged together.

Note that this result contrasts with other recent empirical studies in accounting that have used the MES (e.g., Henderson and Kaplan 2005; Shafer 2008). Those studies found that the MES items loaded on multiple factors generally corresponding with the a priori dimensions of the scale such as moral equity and relativism. Apparently, our Hong Kong participants did not make a clear distinction among these aspects of ethical judgments. The failure of the MES items to load on distinct dimensions is later recognized as a limitation of our study.

As described in this section, we constructed scales for our continuous measures by averaging the responses to individual items. These scales were used for purposes of testing the potential effects of demographic measures on responses and to provide a basis for correlation analysis. In the structural equation models, the individual items comprising each scale were used as the indicators for each latent construct in accordance with standard practice. The individual indicators for the ethical climate and PRESOR constructs are illustrated in Appendix 2. The individual indicators for the ethical judgment constructs include the overall ethical judgments and responses to the five MES items for each of the individual earnings management scenarios, while the individual indicators for behavioral intentions include the two behavioral intention measures for each of the scenarios.

The initial use of exploratory factor analysis followed by confirmatory factor analysis for scale validation is consistent with the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) in their influential article. These authors suggest (p. 412) that, rather than viewing exploratory versus confirmatory analysis as a strict dichotomy, these approaches may be viewed as a part of an ordered progression. This progression may begin with a strictly exploratory approach (in which there is no prespecification of the number of factors) as adopted in the current study, and proceed through a variety of approaches that culminate with a confirmatory analysis of the measurement model that achieves adequate model fit.

To simplify the presentation, the model in Fig. 4 does not include the correlations among the variables. The latent constructs at each step in the model (i.e., ethical climates and stockholder/stakeholder views) were all significantly correlated with each other, and these correlations were controlled for in the model.

We recognize that partial mediation was not documented in our empirical model—only direct associations between the stockholder view and behavioral intentions and indirect associations between the stakeholder view and behavioral intentions (through ethical judgments) were found. However, a fully mediated conceptualization of the relationships between PRESOR attitudes and ethical decision making places additional restrictions on the model by not allowing for the presence of direct paths from PRESOR attitudes to behavioral intentions. Undoubtedly, the relatively poor fit of the fully mediated model tested is due to the fact that it did not allow the presence of the significant paths from the stockholder view to behavioral intentions.

References

Ahmed, M. M., Chung, K. Y., & Eichenseher, J. W. (2003). Business students’ perceptions of ethics and moral judgment: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Business Ethics, 43, 89–102.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Axinn, C. N., Blair, J. E., Heorhiadi, A., & Thach, S. V. (2004). Comparing ethical ideologies across cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 54, 103–119.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. New York: Doubleday.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Bruns, W. J., & Merchant, K. A. (1990). The dangerous morality of managing earnings. Management Accounting, 72, 22–25.

Byrne, B. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS—Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 64–73.

Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah, K. P., & Victor, B. (2003). The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 46, 127–141.

Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73, 667–674.

Dawley, D., Houghton, J. D., & Bucklew, N. S. (2010). Perceived organizational support and turnover intention: The mediating effects of personal sacrifice and job fit. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150, 238–257.

Elias, R. Z. (2002). Determinants of earnings management ethics among accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 40, 33–45.

Elias, R. Z. (2004). The impact of corporate ethical values on perceptions of earnings management. Managerial Auditing Journal, 19, 84–98.

Fischer, M., & Rosenzweig, K. (1995). Attitudes of students and accounting practitioners concerning the ethical acceptability of earnings management. Journal of Business Ethics, 14, 433–444.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Furr, R. (2011). Scale construction and psychometrics for social and personality psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

García-Meca, E., & Sánchez-Ballesta, J. P. (2009). Corporate governance and earnings management: A meta-analysis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17, 594–610.

Greenfield, A. C., Norman, C. S., & Wier, B. (2008). The effect of ethical orientation and professional commitment on earnings management behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 419–434.

Groves, K. S., & LaRocca, M. A. (2011). An empirical study of leader ethical values, transformational and transactional leadership, and follower attitudes toward corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 103, 511–528.

Henderson, B. C., & Kaplan, S. E. (2005). An examination of the role of ethics in tax compliance decisions. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 27, 39–72.

Houghton, J. D., & Jinkerson, D. L. (2007). Constructive thought strategies and job satisfaction: A preliminary examination. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22, 43–53.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6, 5–16.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1991). The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In N. C. Smith & J. A. Guelch (Eds.), Ethics in marketing (pp. 775–784). Irwin: Homewood, IL.

Hunt, S. D., Wood, V. R., & Chonko, L. B. (1989). Corporate ethical values and organizational commitment in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 53, 79–90.

Klein, A. (2002). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 375–400.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford.

Lämsä, A.-M., Vehkaperä, M., Puttonen, T., & Pesonen, H.-L. (2008). Effect of business education on women and men students’ attitudes on corporate responsibility in society. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 45–58.

Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 175–194.

Merchant, K. A. (1989). Rewarding results: Motivating profit center managers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Merchant, K. A., & Rockness, J. (1994). The ethics of managing earnings: An empirical investigation. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 13, 79–94.

Parboteeah, K. P., Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Sakano, T. (2005). National culture and ethical climates: A comparison of U.S. and Japanese accounting firms. Management International Review, 45, 459–481.

Petty, R. E., Wegener, D. T., & Fabrigar, L. R. (1997). Attitudes and attitude change. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 609–647.

Rosenzweig, K., & Fischer, M. (1994). Is managing earnings ethically acceptable? Management Accounting, 75, 31–34.

Shafer, W. E. (2008). Ethical climate in Chinese CPA firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33, 825–835.

Shafer, W. E. (2009). Ethical climate, organizational-professional conflict and organizational commitment: A study of Chinese auditors. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 22, 1087–1110.

Shafer, W. E., Poon, M. C. C., & Tjosvold, D. (2013a). An investigation of ethical climate in a Singaporean accounting firm. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 26, 312–343.

Shafer, W. E., Poon, M. C. C., & Tjosvold, D. (2013b). Ethical climate, goal interdependence, and commitment among Asian auditors. Managerial Auditing Journal, 28, 217–244.

Shafer, W. E., & Simmons, R. S. (2008). Social responsibility, Machiavellianism and tax avoidance: A study of Hong Kong Tax professionals. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 21, 695–720.

Shafer, W. E., & Wang, Z. (2011). Effects of ethical context and Machiavellianism on attitudes toward earnings management in China. Managerial Auditing Journal, 26, 372–392.

Singhapakdi, A., Karande, K., Rao, C. P., & Vitell, S. J. (2001). How important are ethics and social responsibility? A multinational study of marketing professionals. European Journal of Marketing, 35, 133–153.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S. J., Rallapalli, K. C., & Kraft, K. L. (1996). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: A scale development. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 1131–1140.

Smith, D., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2004). Structural equation modeling in management accounting research: Critical analysis and opportunities. Journal of Accounting Literature, 23, 49–86.

Treviño, L. K., Butterfield, K. D., & McCabe, D. L. (1998). The ethical context in organizations: Influence on employee attitudes and behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8, 447–476.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1987). A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 9, 51–71.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 101–125.

Waldman, D., de Luque, M. S., Washburn, N., & House, R. (2006). Cultural and leadership predictors of corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries. Journal of International Business, 37, 823–837.

Xie, B., Davidson, W. N., & DaDalt, P. J. (2003). Earnings management and corporate governance: The role of the board and the audit committee. Journal of Corporate Finance, 9, 295–316.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shafer, W.E. Ethical Climate, Social Responsibility, and Earnings Management. J Bus Ethics 126, 43–60 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1989-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1989-3