Abstract

Background

Post-stroke depression (PSD) occurs in at least one-third of stroke survivors, is associated with worse functional outcomes and increased mortality, and is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of an electronic medical record-based system intervention to improve the proportion of veterans screened and treated for PSD.

Design

Quasi-experimental study comparing PSD screening and treatment among veterans receiving post-stroke outpatient care one year prior to the intervention (the control group) to those receiving outpatient care during the intervention period (the intervention group); contemporaneous data from non-study sites included to assess temporal trends in depression diagnosis and treatment.

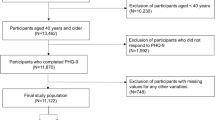

Participants

Veterans hospitalized for ischemic stroke and/or receiving primary care (PC) or neurology outpatient follow-up within six months post-stroke at two (Veterans Affairs) VA Medical Centers.

Interventions

We formed clinical improvement teams at both sites. Teams developed PSD screening and treatment reminders and designed tailored implementation strategies for reminder use in PC and neurology clinics.

Main Measures

Proportion screened for PSD within 6 months post-stroke; proportion screening positive for PSD who received an appropriate treatment action within 6 months post-stroke.

Key Results

In unadjusted analyses, PSD screening was performed within 6 months for 85% of intervention (N = 278) vs. 50% of control (N = 374) patients (OR 6.2 , p < 0.001), and treatment action was received by 83% of intervention vs. 73% of control patients who screened positive (OR 1.8 p = 0.13). After adjusting for intervention, site and number of follow-up visits, intervention patients were more likely to be screened (OR 4.8, p < 0.001) and to receive a treatment action if screened positive (OR 2.45, p = 0.05). Analyses of temporal trends in non-study sites revealed no trend toward general increase in PSD detection or treatment.

Conclusions

Automated depression screening in primary and specialty care can improve detection and treatment of PSD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS. Frequency of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke. 2005;36:1330–40.

Paolucci S, Gandolfo C, Provinciali L, Torta R. DESTRO Study Group. The Italian multicenter observational study on post-stroke depression (DESTRO). J Neurol. 2006;253:556–62.

Jia H, Damush TM, Qin H, Ried LD, Wang X, Young LJ, Williams LS. The impact of poststroke depression on healthcare use by veterans with acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2796–2801.

De Wit L, Putman K, Baert I, Lincoln NB, Angst F, et al. Anxiety and depression in the first six months after stroke. A longitudinal multicentre study. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1858–66.

American Heart Association Heart and Stroke Statistics; http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier = 1200026. Accessed March 18, 2011.

Parikh R, Robinson R, Lipsey J, Starkstein S, Fedoroff P, Price T. The impact of poststroke depression on recovery in activities of daily living over a 2-year follow-up. Archives of Neurology. 1990;47:785–9.

Kauhanen M, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, Brusin E, Mononen H, et al. Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke. 1999;30:1875–80.

Lai SM, Duncan PW. Stroke recovery profile and the modified Rankin assessment. Neuroepidemiology. 2001;20:26–30.

Williams LS, Ghose S, Swindle RW. The effect of depression and other mental health diagnoses on mortality after ischemic stroke. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1090–5.

Ghose S, Williams LS, Swindle R. Depression and other mental health diagnoses after stroke increase inpatient and outpatient medical utilization 3 years post-stroke. Medical Care. 2005;43:1259–64.

Williams LS, Kroenke K, Bakas T, Plue LD, Brizendine E, Tu W, Hendrie H. Care-management of post-stroke depression: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2007;38:998–1003.

Robinson RG, Jorge RE, Moser DJ, Acion L, Solodkin A, et al. Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA; 2008;299:2391–2400.

Hackett ML, Anderson CS, House A, Xia J. Interventions for treating depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Oct 8;(4):CD003437.

Mitchell PH, Veith RC, Becker KJ, Buzaitis A, Cain KC, et al. Brief psychosocial-behavioral intervention with antidepressant reduces poststroke depression significantly more than usual care with antidepressant: Living Well With Stroke: randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2009;40:3073–8.

Paul SL, Dewey HM, Sturm JW, Macdonell RA, Thrift AG. Prevalence of depression and use of antidepressant medication at 5-years poststroke in the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study. Stroke. 2006;37:2854–5.

Ried LD, Tueth MJ, Jia H. A pilot study to describe antidepressant prescriptions dispensed to veterans after stroke. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2006;2:96–109.

www.app.hospitalcompare.va.gov/index.cfm, accessed March 18, 2011.

Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, et al. Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Med Care. 2003;41:669–80.

Busch SH, Leslie D, Rosenheck R. Measuring quality of pharmacotherapy for depression in a national health care system. Med Care. 2004;42:532–42.

Cully JA, Zimmer M, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Quality of depression care and its impact on health service use and mortality among veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1399–1405.

Charbonneau A, Parker V, Meterko M, et al. The relationship of system-level quality improvement with quality of depression care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:846–51.

Damush TM, Plue L, Bakas T, Schmid A, Williams LS. Barriers and facilitators to exercise among stroke survivors. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2007;32(6):253–62.

Stefos T, LaVellee N, Holden F. Fairness in prospective payment: a clustering approach. Health Serv Res. 1992;27:239–61.

Szabo CR. 2005 Facility complexity model. NLB Human Resources Committee, Washington: Veterans Health Administration; 2005.

Reker DM, Hamilton BB, Duncan PW, Yeh SC, Rosen A. Stroke: who’s counting what? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:281–9.

Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, Altschuler A, de Pillis E, Hernandez J, Gordon NP. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1009–29.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:1–7.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Williams LS, Brizendine EJ, Plue L, Bakas T, Tu W, Hendrie H, Kroenke K. Performance of the PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:635–8.

Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. IMPACT Investigators. Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45.

Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Felker B, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in Veterans’ Affairs primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:9–16.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–21.

Felker BL, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Developing effective collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8:12–6.

Williams JW Jr, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:91–116.

Dickinson LM, Dicinson WP, Rost K, et al. Clinician burden and depression treatment: disentangling patient- and clinician-level effects of medical comorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1763–9.

Liu CF, Bolkan C, Chan D, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF. Dual use of VA and non-VA services among primary care patients with depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:305–11.

Cannon DS, Allen SN. A comparison of the effects of computer and manual reminders on compliance with a mental health clinical practice guideline. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:196–203.

Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Lower JH, Gilbert T, Kapoor WN, Schulberg HC. A randomized trial using computerized decision support to improve treatment of major depression in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:493–503.

Dobscha SK, Corson K, Hickam DH, Perrin NA, Kraemer DF, Gerrity MS. Depression decision support in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:477–87.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a VA HSR&D Merit Review grant (IMV 04–096) and the VA HSR&D Stroke QUERI (STR 03–168). Portions of these data were presented at the VA National QUERI meeting, Phoenix, AZ, 12/11/2008 and at the American Stroke Association International Stroke Meeting, San Antonio, TX, 2/19/2010.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

There are no known conflicts of interest with any of the authors that relate to the work done in this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Appendix

Table 4. ICD-9 codes used to identify ischemic stroke and depression diagnoses (PDF 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, L.S., Ofner, S., Yu, Z. et al. Pre-post Evaluation of Automated Reminders May Improve Detection and Management of Post-stroke Depression. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 852–857 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1709-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1709-6