Abstract

To date, investment risk has largely been the Cinderella of Defined Contribution (DC) investment default design – at least in the growth phase of the journey – with its more glamorous sister, investment return, tending to steal the limelight. But all this has changed in the wake of the recent financial market turmoil. Investment risk is now fast becoming the belle of the ball. Part of the reason behind this relative neglect of investment risk is the fact that it has not really been fully understood or defined in an appropriate way for DC savings. Taking a long-term, perhaps over 30–40 years, view and modelling the level and variability of outcomes has generally always suggested that the price of managing risk has always been too great for the benefit that it brings. Lifestyling has traditionally been the medicine for dealing with investment risk, which is fine in the run up to retirement, although lifestyle programmes and glide-path designs can be greatly improved where the additional complexity can outweigh the operational cost that it brings. Traditionally, however, lifestyling has done little to manage risk for those members who are not in this pre-retirement phase of their life. In this short opinion piece, we go back to basics and redefine investment risk in a DC context, suggesting new DC-specific measures to help us get a handle on investment risk, and exploring how DC plan fiduciaries can assess how much risk should be built into a default investment programme and how a defaulting member's exposure to that risk can be more effectively managed over their DC journey. We hypothecate that DC plan fiduciaries have a vital role to play and that they need to subtly, but quite fundamentally change the way that they approach the setting of their default investment strategy – focusing more on understanding their membership, its retirement outcome objectives, its investment return needs and its investment risk tolerances, as well as focusing more on managing the default programme more proactively against some clear strategic objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Historically, investment default strategies in Defined Contribution (DC) pension plans have tended to focus rather blindly on achieving maximum investment return until a few years before retirement, and only then beginning to think about investment risk by switching into ‘protection’ assets through an automated lifestyle programme.

By the nature of DC, investment risk lies largely with each and every member rather than the plan sponsor. However, often the focus is on only one aspect of this risk that a member will retire with an insufficient or unsatisfactory level of retirement income. Although this is clearly important, there is often a low level of awareness of the other objectives that a member may have and the other risks he or she may face, such as the degree of uncertainty around retirement prospects, especially focusing on the downside potential, for members and the volatility of the DC journey itself.

In my experience, the concept of DC investment risk is often poorly understood by many plan fiduciaries and, as a result, is often inadequately addressed and considered in both the design and monitoring of DC investment default strategies.

Little, if any, consideration has historically been given to what investment risk really means in a DC context, what level of risk members can really cope with and how risk can be better measured and more effectively managed on behalf of a defaulting DC member.

The recent financial crisis has changed our perspective on investment risk and, with the continued, even accelerated, growth of DC pension assets, the time has come to readdress and realign the investment risk/return balance.

In this short opinion piece, we propose ways for plan fiduciaries to go about establishing more member-focused and risk/return balanced default investment strategies. We start by going back to basics.

RISK FROM A MEMBER’S PERSPECTIVE

As highlighted previously, I believe there are three elements that combine to form a DC member's retirement savings objectives (Figure 1), namely:

-

level of outcome;

-

variability of outcome;

-

volatility of journey.

In essence, ‘risk’ to a DC member is then the chance of not achieving their retirement savings objectives.

Now, in an ideal world, a member would have absolute certainty about their retirement outcome and have no volatility in the journey, but the reality is that most DC members need to take at least some risk in order to get the return required to achieve a satisfactory or adequate pension income.

The challenge therefore is for a member to effectively create a ‘journey plan’ that balances his or her expected ability to contribute with his or her risk tolerance at differing points along the journey – we need to recognise that these things will change quite substantially for most people over time. Of course, experience is never quite as we expect – sometimes things are better and sometimes worse – and therefore this journey plan needs to be dynamic over time. Some degree of ‘flight control’ is needed.

DYNAMICALLY MANAGING THE JOURNEY PLAN

I believe that there are three ‘levers’ that act to control and manage a member's DC journey (Figure 2):

-

contribution rate;

-

investment risk;

-

outcome (that is, retirement age/income level).

For example, if a member suffers a period of lower than expected investment return and is behind their journey plan, then that member may decide either to increase his or her contributions, accept an inferior outcome (for example, lower pension and/or later retirement age) or else even increase investment risk in the hope of recovering. A member may even decide to do a combination of these things. Of course, this does rely on the member in practice having the ability to use these ‘levers’ in this way. Can the member actually afford to increase contributions? Or afford to retire on a lower pension? And so on.

From this, we conclude that a member should only take investment risk if he or she has enough flexibility in the other levers to recover from any negative experience arising from taking that risk. Therefore, a member's ability to take risk depends on the amount of flexibility he or she has around contributions and retirement outcome.

Getting DC members to create a journey plan, albeit in quite simplistic ways, is now something we are beginning to see in practice with the annual benefit statement being used as a mechanism to play back to the member, how he or she is progressing against their plan and discussing what action, if any, might be required. In this way, good experience might be ‘banked’ if a member is ahead of their journey plan, and a lower risk approach then adopted going forward to create a possibly less choppy landing at the desired level of pension at retirement.

Journey planning is a very powerful and tangible tool to help members better understand and manage risk over time.

THE ROLE OF THE FIDUCIARY

Much of the above, of course, is quite theoretical and relies on a DC member having the ability and willingness to take such an active role. Practical experience of DC has shown us all that the majority of members tend not to take this active role, and therefore the question of how this governance void should be filled for members is raised. Fiduciaries, be they trustees or some other governing body, can, and arguably even should, play a role here (Figure 3) and, by doing so, make a very real and tangible improvement to the outcome, which their plan members will get at retirement.

The most obvious and common way for fiduciaries to supplement the member's individual governance budget is through the application of default strategies.

An effective investment default strategy should consider all of the above factors with a view to helping defaulting members successfully meet their objectives. The most important factor in determining an investment default strategy is to ensure that it is built around an understanding of the membership's needs and objectives, including their tolerance to risk – and, from our experience, this profile can be significantly different between different DC plans.

UNDERSTANDING THE MEMBERSHIP

Therefore, fiduciaries need to answer such questions as: what are the investment needs of their DC membership? How much risk can their membership cope with and what level of return do they need to achieve an adequate retirement outcome?

Understanding the profile of a DC membership involves recognising that there are various types of member groups, who will have different attitudes towards and ability to take risk. This can be based on demographic factors such as age and sex, but also upon measures of wealth, education, financial competence and level of engagement. Membership analysis like this is not just something which should be conducted once and not revisited. A plan and its membership will constantly evolve over time, and so should the fiduciary's approach to risk and investment strategy.

The graph below (Figure 4), for example, illustrates the distribution of member risk tolerance by age across an example DC plan. In this graph, the size of the circle is proportionate to the percentage of the overall membership that fits within the respective age group and at the respective risk tolerance level.

Indeed, by then considering different segments within the membership (for example, by business unit, location and so on) the fiduciary can begin to understand the diversity and segmentation of risk tolerance across the plan's membership as well (Figure 5).

I believe that by analysing the membership in this way, fiduciaries are better able to design an investment structure that meets the needs of their plan's membership.

An analysis of the membership and, in particular, its risk tolerance distribution can allow fiduciaries to assess whether their, maybe, traditional lifestyle approach might be over simplistic in meeting the risk and return needs of members, and whether it is time to consider a more sophisticated design with a view to more effectively meeting member needs.

SETTING CLEAR STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES

To really assess whether a default investment strategy is working well, there needs to be an objective method of performance assessment. In setting strategic objectives, fiduciaries should be focussing on the retirement outcomes required by the distinct groups within the membership. This analysis should ideally also consider how external factors, such as state benefits and other pension arrangements will impact members.

Using the results of the membership analysis, fiduciaries should be able to set clear strategic objectives for their default investment strategy in terms of the levels of risk and returns inherent in achieving the desired outcomes for members.

Implicit within the setting of these objectives, there needs to be some quantifiable measures of investment risk and return that fiduciaries should consider and incorporate into their objectives.

MEASURES OF INVESTMENT RISK

Traditionally, investment risk has been considered as a tracking error or as a fund ‘Value at Risk’ in monetary terms. However, these measures of risk do not convey the member's ability to be able to take risk and ignore the consequences that member's experience. Of course, the nature of DC is that investment risks are borne solely by the member and any losses have to result in lower pensions, more working years or saving more. The challenge for fiduciaries is how to quantify, set an appropriate level for and then communicate, the level of investment risk inherent in a strategy, enabling members to take appropriate action in response to poor outcomes.

As a result, I believe that members and fiduciaries should be using risk measures that help them to understand how members’ outcomes can change.

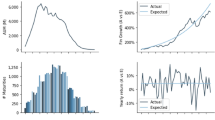

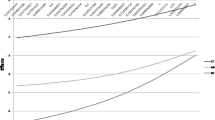

Fiduciaries should start by considering the long-term picture. Long-term projections can be used to estimate an expected level of pension and a range of outcomes around retirement. From this, one can simplify the presentation of results to two metrics (Figure 6):

-

Expected Replacement Ratio (RR): The pension a member expects to receive expressed as a proportion of their final salary before retiring. Considering RR reduces the impact of inflation from the final salary.

-

Pension at Risk at Retirement: There is a 1 in 20 chance that RR at retirement will reduce from its expected level by at least this amount. This provides members and fiduciaries with information on the extent of a potential reduction in RR at retirement.

Fiduciaries of DC plans should consider how the expected outcome and range of potential outcomes meet the needs of the different categories of member.

However, one should be aware that long-term projections used in isolation can steer members and fiduciaries towards holding (or purchasing) high proportions of risky assets due to the long-term bias of such projections. Therefore, short-term risk should also be considered.

Although the absolute level of risk is a consideration, so too is the point in the member's life at which the member is exposed to the risk. For example, consider a member 5 years from their anticipated retirement date who suffers a significant fall in the value of his DC account. He may have to continue to work and save 5 years longer than he had planned in order to achieve his planned level of pension, essentially doubling his remaining working life. In contrast, a member who suffers the same fall in account value with the same expected retirement deferral implications, but who is currently 20 years from retirement, has more time to adjust his income expectations and/or retirement plans.

To consider short-term risk, fiduciaries should ask themselves questions like: how many years members may need to delay retirement by, or by how much should they increase their contributions, to recover from poor market outcomes?

These new ways of thinking about uncertainty build upon the ‘3 levers’ of member risk that were previously identified (Figure 7):

-

‘Contributions at Risk’ can be considered as a short-term measure of risk, relating to how much extra a member would have to contribute to their DC pot to counteract an extreme investment shock.

-

‘Retirement at Risk’ considers how many years a member may have to delay their retirement for in order to recover from a significant negative investment shock. This becomes more of an influential measure as members approach retirement and are unable or unwilling to adjust their target retirement date.

-

‘Pension at Risk’ is a measure of risk that aims to quantify the reduction in a member's retirement income that might be created by a significant negative investment shock.

In practice, I have found that the ‘Retirement at Risk’ measure is often the most tangible and useful to consider (Figure 8). Obviously, a member's ability to change their retirement age may be subject to employment or other constraints and, generally speaking, fiduciaries should seek to minimise this risk as the member approaches retirement, or at least communicate this risk so that members understand the investment risk they are exposed to.

The alternative measures of risk described above help members to understand the risks they are actually taking within their DC plan, and how the incidents of those risks may affect their ability to retire at the level of pension they are expecting. In addition, fiduciaries can also use these risk measures to help design an appropriate and optimal investment strategy, which matches the needs and risk profile of the membership. This can include: the type of de-risking strategy offered to members, the asset classes that are utilised within the plan, the nature of the default option and the range of self-select choices available.

CONCLUSION

Members of DC plans should only take risk when they have the flexibility to adapt their journey plan or objectives to recover from a poor outcome. In establishing a DC plan's investment strategy, fiduciaries need to analyse and understand their membership's tolerance to risk.

Fiduciaries can help members to understand the risks inherent in their DC fund by providing easy-to-understand tangible information regarding the possible impact of bad events occurring during the journey to retirement. Measures that focus on both the short-term and long-term will enable members (and fiduciaries on a member's behalf through a default programme) to create and maintain a strategy that better manages risk and expectations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, G. Considering investment risk in a DC pension plan. Pensions Int J 16, 33–38 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/pm.2010.35

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/pm.2010.35